Yale’s endowment, explained

The dynamics behind endowment spending and investment are nuanced, but they provide important context for ongoing campus debate over endowment usage and best practices.

Isaac Yu, Audience Editor

Yale’s endowment is often characterized as a bottomless pot of cash.

Indeed, the endowment just reached $41.4 billion after gaining 0.8 percent in 2022, making it the second largest university endowment in the country, after Harvard’s. Its growth is overseen by hundreds of employees who solicit donations and invest University funds through a long-tested proprietary management model.

“The endowment is the single largest source of revenue for the university’s budget,” Vice President for Finance and Chief Financial Officer Stephen Murphy ’87 wrote in an email to the News. “Outside of the medical school, the endowment generates over half of the [University’s] funding.”

The endowment has become a focal point for students calling on the University to revise its funding priorities. Last February, the Endowment Justice Coalition filed a complaint against the University for its continued investment in fossil fuels.

Meanwhile, Yale spends just a tiny fraction of its endowment in any given year — usually around five percent. The dynamics behind endowment spending and investment are nuanced, but they provide important context for ongoing campus debate over endowment usage and best practices.

Here’s a look under the hood of Yale’s endowment.

Restricted funds

Despite popular understanding, the endowment is not a single pool of easily accessible funds, but is instead composed of about 8,000 individual accounts, each of which represents a unique gift to the University.

When a donor decides to give to Yale, they are rarely forking out cash with no strings attached. Yale allows donors to decide how they would like their gifts to be used. Thus, donations are often earmarked for specific purposes — for instance, funds might go toward undergraduate financial aid, a new building or a professorship.

In many cases, the University is contractually obligated to spend and invest endowment funds according to these purposes. About 75 percent of the endowment — which amounts to over $31 billion — is therefore “restricted” to donor-stipulated uses.

Despite the fund restrictions, the University maintains its own fundraising priorities, according to Vice President for Alumni Affairs and Development Joan O’Neill. These include financial aid, endowed professorships, research funds, art collections, athletics, interdisciplinary teaching funds, equipment funds and more.

“Our job in the development office is to work to connect our potential donors with [these] priorities,” O’Neill wrote in an email to the News. “Some gifts are very broad, such as funding student financial aid, while others are narrower, such as supporting the care and maintenance of specific parts of our [art] collections.”

The development office begins with an idea of what it wants its restricted funding to look like and solicits gifts accordingly.

O’Neill said that about half the money the University has raised for its five-year “For Humanity” capital campaign has come in the form of gifts that are funneled toward the endowment, as opposed to gifts for new facilities or so-called “current use gifts,” used for short-term discretionary spending.

These endowment gifts are disbursed as part of the endowment’s annual budget contribution. In 2021, out of the endowment’s $1.5 billion contribution, 25 percent went toward teaching and research, 24 percent went toward “general support,” 19 percent went toward facilities and operations, 18 percent went toward financial aid and 14 percent went toward “other specific purposes.”

“New gifts to the endowment are one of the most important ways that we grow the endowment, as this allows the value to grow by both new principle and investment returns,” O’Neill wrote in an email to the News.

Budget contribution and the spending rule

The University’s rationale for prolonged endowment growth is captured in the guiding principle of “intergenerational equity,” a concept pioneered by the late Yale economist and Nobel laureate James Tobin.

In 1974, Tobin famously wrote that “the trustees of endowed institutions are the guardians of the future against the claims of the present. Their task in managing the endowment is to preserve equity among generations.” Intergenerational equity has guided Yale’s endowment investment policy ever since.

On its endowment overview website, the University writes that “unlike with a savings account or a rainy-day fund, only a portion of [the endowment] is available for spending in any given year, in order to preserve the endowment’s longevity.”

Specifically, Yale seeks to spend approximately 5.25 percent of its endowment annually, as this is the amount that the Investments Office estimates will “allow for sustained growth given projected returns.”

After accounting for an expected four percent inflation rate, the Investments Office therefore aims to grow the endowment by at least 9.25 percent annually to maintain its real value while providing budget funds to the University.

However, given Yale’s average annual return of 12 percent over the 10-year period ending in June 2022, the 5.25 percent spending distribution seems conservative. Over the last decade, Yale could have spent an additional three percent of the endowment while remaining profitable in real terms. In 2021, this would have amounted to an extra $1.27 billion, nearly doubling the endowment’s budget contribution.

The Yale Endowment Justice Coalition’s website points out that if the University spent just 0.97 percent more of its endowment, tuition could be eliminated for all Yale College students. If Yale spent 1.3 percent more of its endowment, it could contribute New Haven’s entire yearly budget.

“Last year, Yale profited from a 40.2 percent return on its investments,” Lumisa Bista ’24, a longtime member of the EJC, told the News. “In comparison, the sum of this return is almost 20 times the yearly operating budget of New Haven. Still, Yale does not pay taxes to the city.”

In justifying its 5.25 percent target contribution, the Investments Office noted that its spending policy is reviewed regularly and adjusted to take into account “portfolio characteristics and market experience.”

The Investments Office also cited long-term market cycles, which more closely match the 5.25 percent rate reflected in the spending policy.

“The last 10 years, which do not represent a full market cycle, saw an extraordinary bull market run, but long-term market returns after inflation have been more muted,” a statement from the Investments Office reads. “As such, we believe that our spending rule remains appropriate given the University’s multi-generational time-horizon.”

But 5.25 percent is just a benchmark; the actual endowment contribution changes every year.

The endowment’s actual annual contribution is determined by a “smoothing” equation, which requires the University to spend a greater percentage of the endowment when the endowment value drops, and a lower percentage when the value rises. This practice creates a cushion when returns fall and compels discipline when they rise.

The smoothing equation is a weighted average of 5.25 percent of the endowment’s value from two years ago — weighted at 20 percent — and last year’s endowment budget distribution — weighted at 80 percent.

Endowment Contribution = 0.2(.0525 * (endowment value from 2 years ago)) + 0.8(last year’s endowment contribution)

A given year’s returns do not begin to impact spending until two years later, when they are gradually incorporated into the calculated contribution.

“The spending rule says to spend 5.25 percent of the ‘rolling average endowment,’ that is the average endowment over many years,” economics professor John Geanakoplos wrote in a June 2020 FAS Senate report. “The rolling average endowment is much more stable than the annual endowment … This smoothing rule formally recognizes the principle that abrupt changes in spending cause unnecessary damage.”

Yale’s investments

For over 35 years, David Swensen managed the University’s endowment under “The Yale Model,” a framework for institutional investing that he developed alongside then-senior endowment director Dean Takahashi. Although Swensen passed away in 2021, the Yale Model has remained the University’s primary investing scheme — and has become the industry standard over the last three decades.

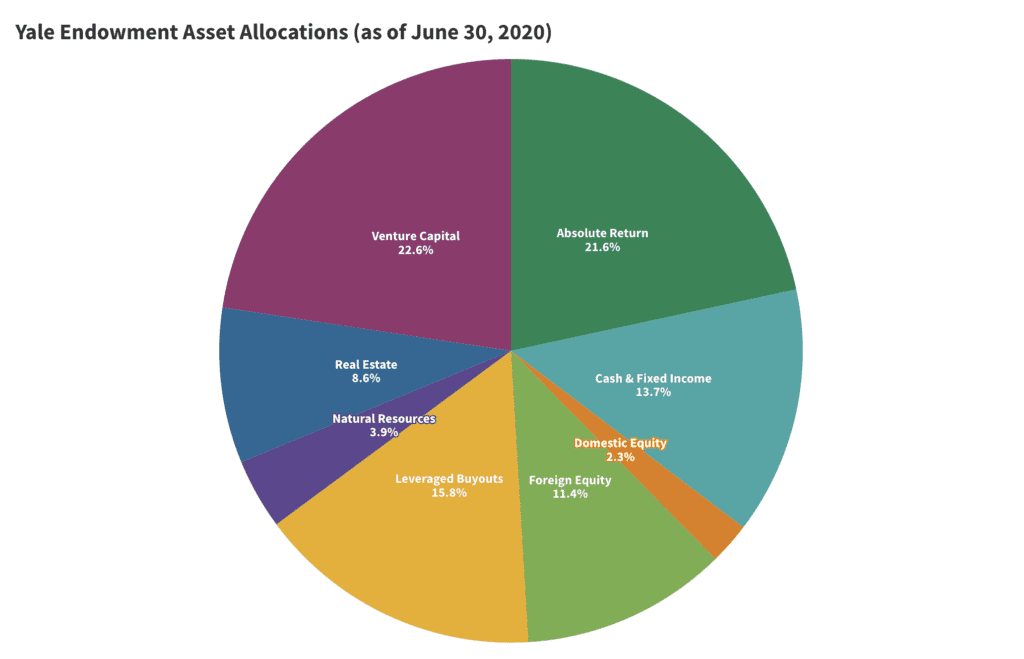

The Yale Model favors broad diversification of assets, allocating less to traditional U.S. equities and bonds and more to alternative investments like private equity, venture capital, hedge funds and real estate.

Yale’s investment strategy depends heavily on alternative investments. As of 2019, they made up about 60 percent of Yale’s portfolio.

Price uncertainty of illiquid assets may artificially inflate Yale’s reported returns, but they have demonstrated superior “return potential and diversifying power.”

In 1989, nearly three-quarters of the endowment was committed to U.S. stocks, bonds and cash. Today, domestic marketable securities account for less than a tenth of the portfolio, while foreign equity, private equity, absolute return strategies and real assets represent over nine-tenths.

Evan Gorelick, Production & Design Editor

“Yale long ago abandoned the traditional 60 percent stock [and] 40 percent bond portfolio, which is having its worst year since the 1930s,” Rutgers Business School professor John Longo wrote in an email to the News. “Yale’s sizable allocation to alternative investments was likely the reason for its positive fiscal year performance.”

Nevertheless, the EJC argues that, while profitable, “these non-traditional asset classes are linked to things like fossil fuels and Puerto Rican debt.”

For years, the endowment has been an embattled issue on Yale’s campus. Endowment justice made national news in 2019 when Yale and Harvard students disrupted the schools’ annual football game to call for divestment. In October 2020, students occupied Cross Campus to demand that the University divest from holdings in the fossil fuel industry and the Puerto Rican debt. Students held a similar rally at Beinecke Plaza in November 2021.

In February 2022, the EJC filed a complaint against the University for its continued investment in fossil fuels, alleging that such investments violate state law. The complaint hinges on a provision of the 2009 Uniform Prudent Management of Institutional Funds Act, which is in effect in every state except Pennsylvania. The act stipulates that tax-exempt nonprofit entities, including universities, must invest with charitable interests in mind.

The EJC acted alongside students who filed similar complaints at Princeton, Stanford, Vanderbilt and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

When divestment activists at Harvard and Cornell took the same approach in 2021 and 2019, respectively, they met with success. Each school moved to divest from the fossil fuel industry within six months of the complaint filing.

“Ethical investing”

Nevertheless, the Investments Office claims to act within its ethical investing policy, which the University first adopted in 1972.

In the decades since, the Investments Office has occasionally reevaluated investments according to its ethics policy. From 1978 through 1994, Yale divested shares of 17 companies operating in South Africa — representing a total market value of approximately $23 million — because of their roles in the country’s apartheid system. In 2006, the Yale Corporation voted unanimously to divest from a Sudanese oil company deemed complicit in mass genocide. In 2022, the University deemed ExxonMobil and Chevron ineligible for investment after adopting more stringent fossil fuel investing principles.

The Corporation Committee on Investor Responsibility, or CCIR, is a subcommittee of the board of trustees that considers and makes recommendations on ethical investing to the rest of the Corporation. The CCIR is supported by the Advisory Committee on Investor Responsibility, or ACIR, whose membership consists of an undergraduate student, a graduate student, two alumni, two faculty and two staff members.

When campus groups and other state and local organizations demanded that the University cancel investments in Puerto Rican bonds and fire investment managers who refused to sell or forgive the debt, the matter was referred to the ACIR.

In January 2018, the ACIR concluded that “divestment from Puerto Rican debt is not warranted when an investor is abiding by the applicable legal framework in a process in which the debtor’s interests are appropriately represented.” Yale has not announced any plans to divest from Puerto Rican debt.

The Investment Committee meets quarterly to review asset allocation policies, endowment performance and strategies proposed by Investments Office staff.

The Yale Investments Office’s softball team, the “Stock Jocks,” was founded in 1985.

Correction, Oct. 24: A previous version of this article said that Harvard and Cornell divested completely from the fossil fuel industry within six months of the complaint filing. In fact, Harvard and Cornell were not completely divested within six months; rather, they took action for long-term divestment in that time. The article has been updated to reflect this.