University blocks large posters, possible protests at Yale-Harvard game

In a Friday morning email to students, University administrators released guidelines restricting banners and possible demonstrations during The Game. The University did not directly respond to questions on whether growing campus tensions related to war in Israel and Gaza prompted the policy updates.

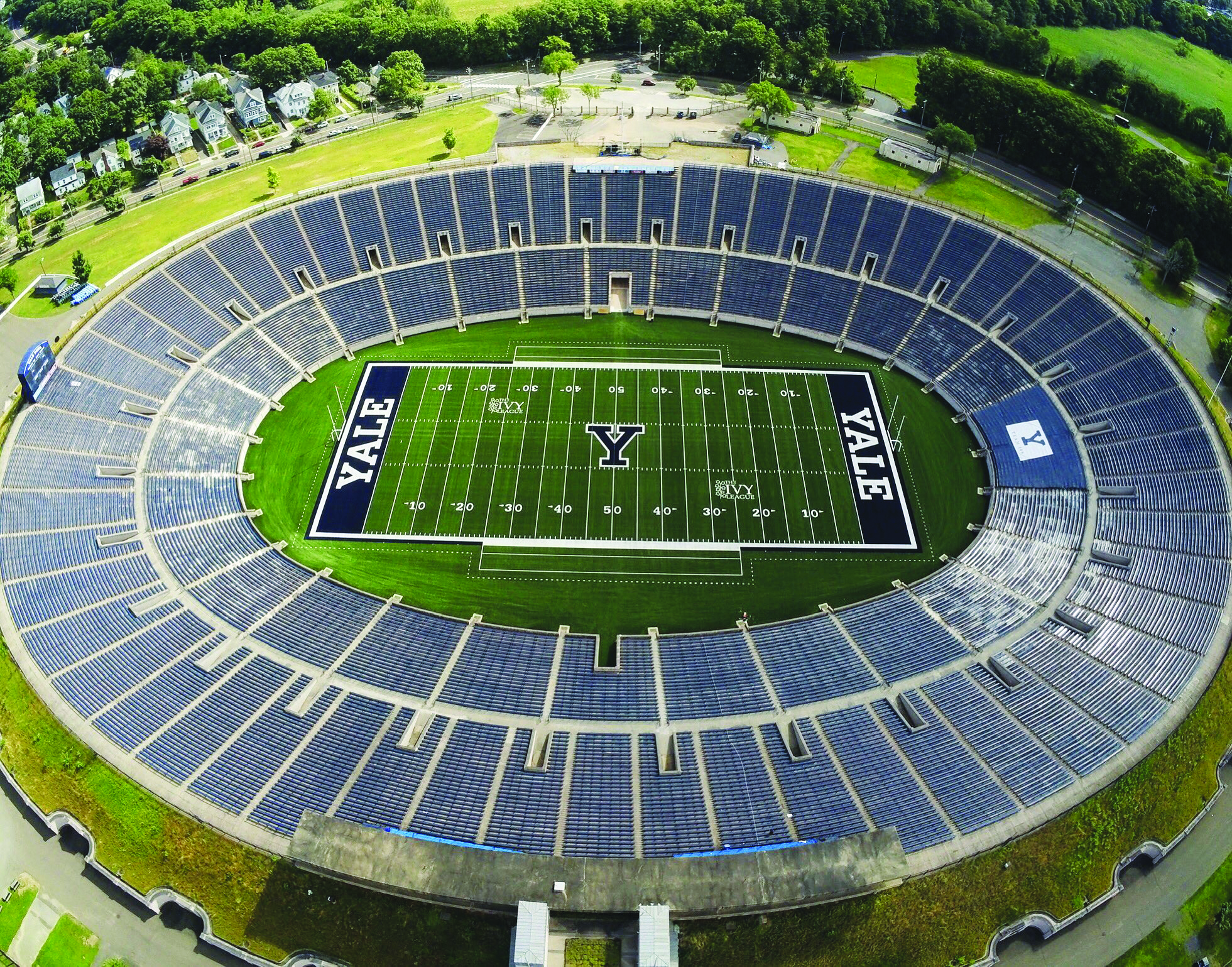

Yale Athletics

Students will not be permitted to bring large banners or signs into the Yale Bowl and “unauthorized spectators” could be subject to arrest if they attempt to access the field during the annual Yale-Harvard game on Saturday, per an email sent to students Friday morning.

In the Nov. 17 message, Associate Vice President for Student Life and Dean of Student Engagement Burgwell J. Howard and Dean of Students and Senior Associate Dean in Yale College Melanie Boyd provided information and resources for the 139th annual Yale-Harvard football game. Among the information provided in the email was a section labeled “Be Smart,” informing students that the University “expects” they will refrain from disrupting the annual sporting event.

In 2021, the last time that Yale hosted The Game, these specific restrictions — the prohibition of “large banners or signs” and the possible arrest of spectators who attempt to access the field — were not publicized to students on that year’s game day information page.

Chief of Yale Police Anthony Campbell wrote to the News that while spectators may bring smaller posters and signs to the Yale Bowl, they cannot bring those that “would obstruct the view of spectators” — such as a banner that needs to be held by more than one individual.

The information comes amid a flurry of student activism, alumni concerns and related occurrences — including protests, petitions, rallies, student safety concerns and, most recently, a doxxing campaign — in the wake of the escalating Israel-Hamas war. Yesterday morning, a truck arrived on Yale’s campus with the names and faces of at least 15 graduate students — most of whom are of color — emblazoned on the vehicle’s sides. The “doxxing truck” has made its rounds at other Ivy League schools, including Harvard University, and was still in New Haven on Friday evening.

The News asked the University if the new policies come in light of growing tensions or in anticipation of student demonstrations on game day, but the University did not directly respond to those questions.

“The Game is a reunion of friends, but ultimately is a sporting event,” Boyd and Howard wrote in their Nov. 17 email. “We expect that all fans will respect the hard work of the student-athletes and will refrain from any disruptions that could detract from the event.”

In 2019, at least 150 Yale and Harvard alumni and students stormed the Yale Bowl field to demand that both universities divest from fossil fuels.

The demonstration delayed the start of the second half of the game and drew national attention, with messages of support for the student activists coming from both Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren and Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders.

“Yale always has concerns about that since 2019,” Campbell told the New Haven Register. “We’re on a constant learning curve with regard to how to deal with disruptions. We have safety plans in place, and if there are any disruptions, we will be able to address it pretty quickly.”

Per Yale’s policy on free expression and peaceable assembly, disruption of University events is not permitted. This includes any activity that might disrupt or interfere with University events or operations, block access to facilities, restrict others’ ability to listen or be heard or create safety concerns.

The New Haven Register reported yesterday that Yale and New Haven are planning on increased police presence at tomorrow’s game.

“Our goal is to provide a safe and enjoyable experience for everyone attending the game,” Campbell wrote in an email to the News. “To achieve this, we have a comprehensive security plan in place, drawing from lessons learned from the past games with high attendance. We are prepared to address any potential disruptions that may occur.”

In a joint social media post earlier this week, student groups at Harvard and Yale described their plans to convene under the scoreboard at halftime while donning keffiyehs, or Palestinian scarves.

The University did not tell the News whether such action by student groups would comply with or violate the regulations promoted today or any of Yale’s existing policies. Since last month, when the war between Israel and Hamas began, Yale has “increased security on and around campus” and reached out to individuals “with ties to the region” to offer support, the University said on Nov. 17.

The University added that its priority has been “the safety and well-being of the campus community,” referring to an Oct. 13 message from Campbell that pointed community members to safety resources.

In a Nov. 3 interview with the News, University President Peter Salovey reaffirmed Yale’s commitment to upholding its policies on freedom of expression despite any “difficult moments” it might create for the administration.

“In general, on whatever side of an issue people are, I think we should encourage open expression,” Salovey said. “I’d like that expression to be one that is informed and responsible; of course, it cannot be one that is threatening, it cannot be harassing, it cannot incite violence but having said that, I don’t think we should encourage behaviors that stifle that expression and that includes canceling people or doxxing people.”

The Woodward report, which guides the University’s policies on freedom of expression and peaceful assembly, was adopted by the University in 1975.

Spencer King contributed reporting.