Nine-year-old girl tours Yale labs after neighbor reported her to police for spraying lanternflies

A neighbor’s call to the police on a young Black girl for spraying lanternflies sparked discourse around the dangers of adultifying Black children and weaponizing the police. A Yale tour led by Black female scientists sought to support the little girl in her love for science.

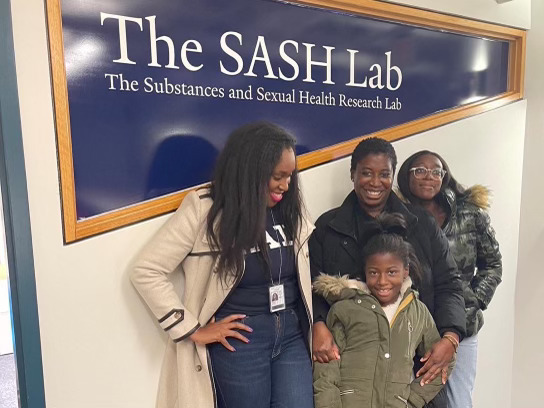

Courtesy of Ijeoma Opara

Nine-year-old Bobbi Wilson of Caldwell, New Jersey was welcomed to Yale for a “Black girl led Science Tour” after a viral incident where her neighbor called the cops on her while she was protecting trees from lanternflies.

The little girl had been spraying a formula to help exterminate spotted lanternflies — an invasive species in New Jersey — when her neighbor reported her to the police, who then stopped and questioned her. In response to this incident, Ijeoma Opara, Yale School of Public Health assistant professor, designed a tour to introduce Bobbi to Black female scientists and reward her for her efforts to save the environment.

“I didn’t want this traumatic experience due to racism to harm Bobbi,” Opara said. “I didn’t want it to prevent her from continuing to explore her environment and from continuing to pursue a career in science.”

The lanternfly incident

On Oct. 22, Gordon Lawshe called the cops on a “real small woman” who was wearing a “hood,” according to a bodycam recording published by CNN.

“There’s a little Black woman, walking, spraying stuff on the sidewalks and trees on Elizabeth and Florence,” Lawshe said in the bodycam recording. “I don’t know what the hell she’s doing, scares me though.”

The “woman” was in fact nine-year-old Bobbi, under 5-feet tall, who was spraying a mixture meant to help exterminate spotted lanternflies. The hood of her hoodie was not on her head, and she was Lawshe’s neighbor of almost eight years from just across the street.

Bobbi made this spray herself — it consisted of water, apple cider vinegar and dishwasher soap. She discovered this recipe and how it could be used to combat the dangers posed by spotted lanternflies on TikTok.

The spotted lanternfly is an invasive planthopper native to Asia. It can cause extensive damage by feeding on the sap found in its host plants, including trees and other plants. New Jersey’s “Stomp it Out!” campaign urges people to extinguish and report the lanternfly when there is a sighting because of the damage the species can cause to crops.

“She was not only doing something amazing for our environment, she was doing something that made her feel like a hero,” Bobbi’s 13-year-old sister Hayden Wilson said at a Nov. 1 Borough of Caldwell Council Meeting. “Our neighbor across the street saw my sister spraying the trees with the solution and didn’t know what she was doing. Instead, he decided it would be appropriate to call the police on my sister.”

Monique Joseph, Bobbi’s mother, also spoke at this meeting, revealing that her daughter had been afraid to leave their house immediately after this happened.

“[Lawshe] did not want to become involved in a confrontation, so he called the Caldwell police to look into the matter,” Gregory Mascera, Lawshe’s attorney, wrote to CNN in an email. “Mr. Lawshe did not call 911 but called the police non-emergency dispatch line. Mr. Lawshe had no reason to believe that he would be putting anyone in harm’s way by calling the police.”

The bodycam footage continued: after the responding officer talked to Joseph, he explained to Lawshe that Bobbi was merely catching lanternflies.

“What a weirdo, huh?” Lawshe said in the video.

A Black female scientist-led tour

When Opara initially heard what happened, she took to Twitter to find the little girl’s family and arrange a science tour at Yale. Opara wanted to encourage Bobbi in her love for science and her environment.

Opara described Lawshe’s call to the police as a “waste of resources” and as an example of “weaponizing the police” against Black people.

“I just didn’t want any young girl who has big enough ideas and big enough dreams to feel demonized for taking the initiative to go above and beyond to save their environment or to explore their interests,” Opara said. “She wasn’t harming anybody. And like many Black children, who are criminalized and punished in school and have the police called on them, a majority of them aren’t doing anything criminal — they’re merely just existing and being Black.”

The Nov. 16 tour began at Opara’s lab, the Substances and Sexual Health Lab at YSPH. Opara’s work seeks to challenge gendered racism and its impact on the health outcomes of racial-ethnic minority youth. Alongside several Black female scientists at Yale, Bobbi was joined by her parents and her sister Hayden.

The next stop on the tour was the Bei lab, where Ife Desamours Adeyeri GRD ’26, a doctoral student in microbial pathogenesis, showed the family around the lab and YSPH’s insectary. Adeyeri, who works with mosquitoes, taught Bobbi about the life cycle of mosquitoes and how they connect to her work studying malaria. Hoping to bring “something good” out of a “terrible situation,” Adeyeri was happy to reinforce Bobbi’s interest in insects and biology.

“I thought it was nice for her to get to see female Black scientists, which is something that I never got to see in person until graduate school,” Adeyeri, who grew up in Florida, said. “That’s an experience I never had that I hope was instrumental to her because I would have definitely appreciated that.”

Up Science Hill, the tour continued in the Horsley lab, where Kristyn Carter, a postdoctoral fellow, explained how she researches diabetes in mice. Carter is the president of the Black Postdoctoral Association at Yale.

Opara described this segment of the tour as “one of the biggest moments” for her, seeing Bobbi’s excitement about the lab mice. Bobbi told the News that this was her favorite part of the tour. She enjoyed learning how Carter worked with mice, even when it came to skin removal and other procedures.

“I was hiding because I didn’t want to see [the mice], but Bobbi was like, ‘Give me more,’” Joseph said. “I made this correlation that wow, Bobbi’s into the sciences.”

The last stop on the tour was the Peabody Museum’s entomology collection. The group met Lawrence Gall, the entomology collections manager, and Nicole Palffy-Muhoray GRD ’16, Peabody’s assistant director of student programs.

“I was also a little girl who liked bugs,” Palffy-Muhoray said during the tour. “I got made fun of for it … so when I hear about a little girl who’s thinking about bugs, I get excited.”

Gall quizzed Bobbi on the definition of entomology and talked to her about “structural color,” which is a form of color created by the refraction of light that is naturally found in insects and bugs.

At the end of the tour, Gall revealed that the Peabody had not yet acquired lanternflies. He asked Bobbi if she could catch some for them from New Jersey.

“If you bring us lanternflies, we’ll make labels with your name on it as the collector, and they’ll become part of the permanent record here at the Peabody Museum as our first lanternfly,” Gall said during the tour.

Bobbi would permanently be listed as a collector in the Peabody’s database, and anyone who uses the lanternfly specimen contributed by Bobbi would have to credit her.

“The [scientists] were young, they were female, they looked like [Bobbi and Hayden],” Joseph explained. “It could have been their auntie, their cousin, their sister. It’s not just this man in a white coat. … Whatever you can see, you can be; it makes it possible.”

Changing the trajectory

The language used by their neighbor was “hurtful and scary” to Bobbi and her family, Joseph described.

Joseph’s biggest concern from this incident was the adultification of Black children. She explained that Black girls and boys have been treated like adults, charged as adults and held in jail cells. To Joseph, it’s important to amplify this story for the people who do not understand “how the language used to describe Bobbi and what she was doing had tones of racism.”

“I brought this conversation to my town because I wanted them to be aware that this language is dangerous,” Joseph said. “We’re not all guaranteed to stay in our little bubble in Caldwell or wherever we live, but if you take this language and you speak it, it could be life or death for someone.”

Joseph is focused on ensuring that Bobbi is emotionally healthy and feels safe to explore her world. Now when Bobbi prepares to go outside independently, Joseph will spend a few minutes talking with her to make sure they both feel safe while she is out. Her mother does not want to sacrifice her child’s chance to explore and grow.

“We can’t live in fear,” Joseph added.

Like Bobbi, Opara grew up in New Jersey and was a “young Black girl who dreamed big,” she said. However Opara’s parents were terrified to have her go outside by herself in the early 1990s because of incidents like these. Her parents did not want anyone calling the cops on her or mistreating her in their absence.

This fear that Black parents in America have stems from society not letting “Black children be Black children,” Opara explained. But actions taken to shield children from potential racism can also threaten their ability to explore and learn from their surroundings.

Opara admitted to not being able to explore her environment the way she would have wished to as a child.

“When you are growing up in this constant state of fear and paranoia because you genuinely believe that society not only doesn’t see you as a human being but that they are willing to harm you because they see you as a criminal — you’re literally just trying to live,” Opara said. “You’re literally just trying to explore as a child.”

Opara wants to use her position of power to change this narrative, to let Black children “live” and be free to “explore like all the other children.” This tour was important to nurturing “Bobbi’s brilliance” and making her feel safe, Opara explained, to remind her that she did nothing wrong.

“These are young women. They are Black, they are scientists, they’re doctors, they’re professors — they’re brilliant,” Joseph said. “It was just beautiful. I wanted to make sure that the Yale community knows from the bottom of my heart, how much they meant to us, … that it gives my girls hope that this can be their reality too.”

Opara described her life’s work as empowering Black girls to be aware of how racist and gendered stereotypes harm them. She hoped to expose Bobbi and Hayden to Black female scientists like herself to inspire their continued engagement with science.

After returning home from the tour, Bobbi worked to catch spotted lanternflies for the Peabody, capturing around twenty from a local tree that was infested with the species. The specimens were shipped to the Peabody for arrival on Nov. 29.

Through this tour, Joseph realized that science was “right up Bobbi’s alley.” Seeing Bobbi’s fascination with understanding the diabetic mice reminded her of when Bobbi helped care for her grandmother. The little girl had wanted to understand why each medication was given to her grandmother and how it worked.

This lanternfly-fighting formula was just one of Bobbi’s forays into science. She enjoys using leaves, flowers and grasses to concoct original mixtures.

“I like to mix things and make potions,” Bobbi told the News. “I like science. … I want to help cure things.”

The spotted lanternfly feeds on over 70 different plant species.