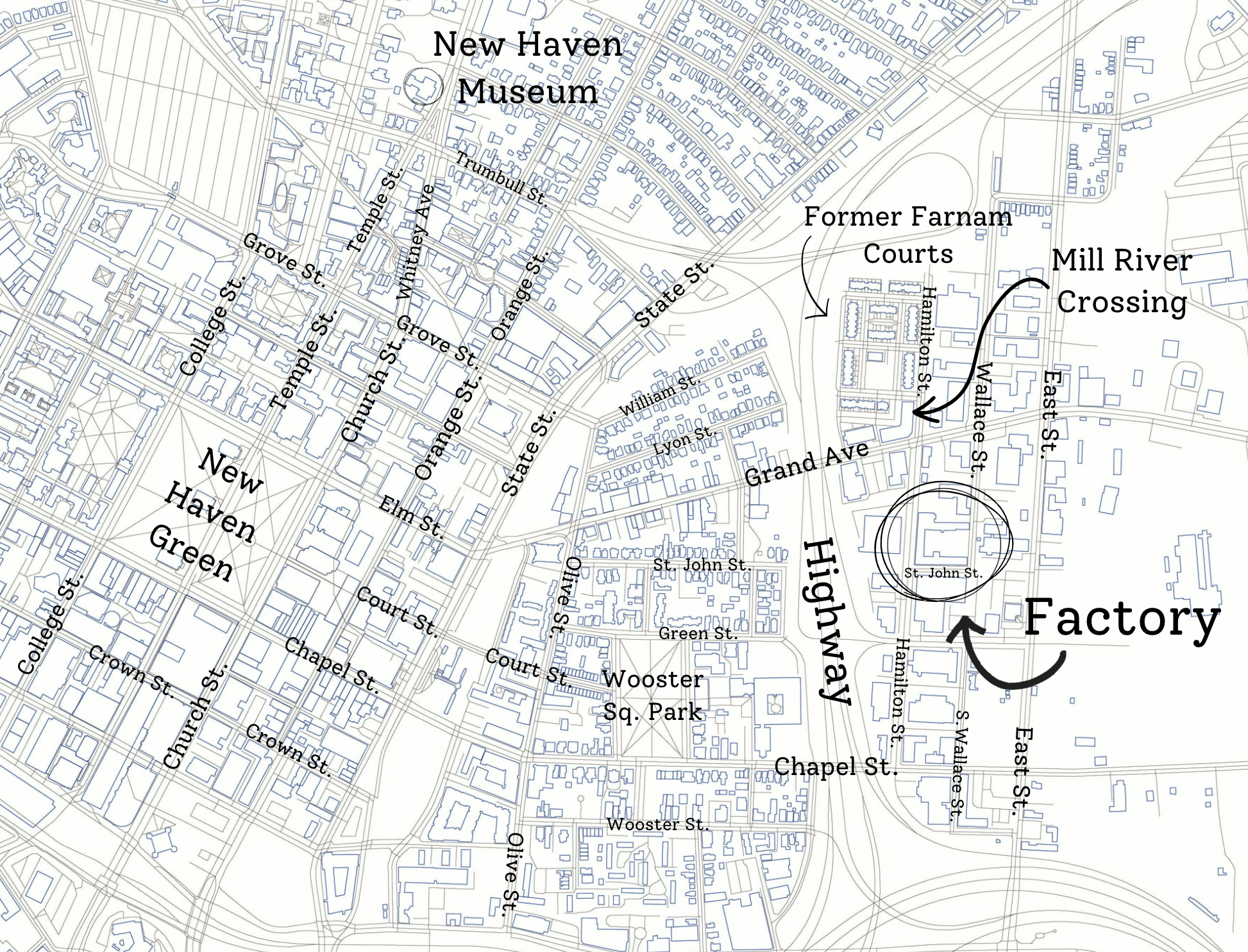

“Everything in here was found in the dumpsters,” Jason Bischoff-Wurstle says, pointing to a blown-up image of Dimitri Rimsky’s art studio. In the photo, a mustachioed man in a fedora pokes his head past the edge of a convex mirror, casting his expectant gaze across a room strewn with a joyous excess of furniture: a disco ball; a bamboo plant; a microphone; several barbershop chairs. This is a photo of the inside of the New Haven Clock Company Factory at the corner of St. John and Hamilton Streets, east of Wooster Square, taken sometime in the 1980s. The image hangs on the orange walls of Bischoff-Wurstle’s FACTORY exhibit at the New Haven Museum.

The exhibit takes visitors through the history of the factory, from life to afterlife. To say the factory has an eventful history would be reductive. Clocksmith Chauncey Jerome, who helped turn clocks from luxuries into everyday consumer goods, built the factory in 1842. It was bought by the New Haven Clock Company in 1853. In the early 20th century, it came under the direction of Walter Camp (better known for revolutionizing American football) who launched the factory into the production of wristwatches. Half the factory was destroyed during New Haven’s urban renewal of the 1950s and 1960s, when much of the surrounding housing was razed and population displaced to make room for a highway.

But when the Clock Company went out of business in the 1950s, the building’s activity didn’t cease. After a couple decades of holding companies leasing individual rooms, Tony Yagovane, a New Haven resident, bought the building in 1980. Here the building was born anew: out of a deteriorating semi-vacant space arose a lively home for artists and weirdos of all stripes.

Yagovane offered the space to people on the cheap (Dimitri Rimsky reports paying 100-200 dollars a month for 1400 square feet) as long as the occupants took care of installing gas, water, and electricity. The low rent attracted an eclectic mix of tenants. Yale School of Architecture students hosted an annual “sex ball” in the factory, complete with murals of intersex people. A mime troupe (Rimsky’s “Petaluers”) worked there, as did Paul Rutkovsky and Beverly Richey’s Papier Mâché Video Institute (a dissident activist art group). Brick ‘n’ Wood (an R&B club) and Kurt’s (a gay bar) also operated from the building.

In later years, the Bad Ass White Boys (a white supremacist biker gang) took up a wing on the second floor, and a cockfighting ring sprung up in the other wing. Traffic slowed through the 2000s, especially in the wake of Yagovane’s death in 2005. In 2011, Occupy Wall Street’s New Haven branch briefly considered taking over parts of the factory. The last official tenant (a strip club) was finally evicted after a court battle in 2019. These last few years, according to Bischoff-Wurstle, are the longest the building has ever been vacant.

Listing the history of the factory building like this usually elicits interest, but it’s a rather boring way to tell a story, as Bischoff-Wurstle well knows. The challenge, he says, was to find a way to bring out the history vividly without devolving into chronological narration. Bischoff-Wurstle worked urban renewal and the factory’s history as, well, a factory, into the exhibit. But he designed the exhibit to celebrate the factory’s afterlives. He dug up images of the factory, documents from the urban renewal period, and artifacts from the various inhabitants, and by interviewing Rutkovsky, Richey, and Rimsky at length: an attempt to move the factory’s more recent (and more off-beat) stories into the realm of official “history.”

What is displayed in museums has been deemed worthy of exhibition. In a way, museums, by assembling records and lending institutional weight to what they display, decide what is and is not history. The factory’s post-clock history isn’t all that old, but Bischoff-Wurstle thinks that by bringing it “into the canon,” it will prevent this “weird nexus place” from being lost forever. Bischoff-Wurstle described the factory as a “place of encounter” and “accidents.” The exhibit, though curated, sought to capture the factory’s spirit of spontaneity, which Bischoff-Wurstle feels has slowly drained from the world we live in.

Photos by Etai Smotrich-Barr

Bischoff-Wurstle is the Director of Photo Archives at the New Haven Museum. He began arranging the FACTORY exhibit in 2018 in collaboration with Gorman Bechard, who helped found the NHDocs documentary film festival, and Bill Kraus, the owner of a firm that focuses on redeveloping historic buildings. Kraus has worked in commercial real estate for over three decades, primarily dealing with rundown buildings that haven’t delivered on their economic potential. The exhibit, which opened in February 2020, was supposed to be the last of three major factory-related projects spearheaded by Bechard, Kraus, and Bischoff-Wurstle. Bechard and Kraus were jointly working on a yet-to-be-released documentary about the factory and its afterlives. At the same time, Kraus was working with the Oregon-based Reed Development Corporation to turn the space into affordable housing for artists.

What exactly “artist housing” meant was a bit of an open question. In the early 2000s, Kraus spearheaded the conversion of an old department store in downtown Bridgeport into 61 “affordable artist live-work” units, which, he said, has been the “catalyst for a renaissance in downtown Bridgeport,” drawing in “hundreds and hundreds of millions of dollars in follow-on development.” It’s not public housing—it’s the “private market with public subsidies.” At the time, this kind of reuse project wasn’t in fashion: cities preferred to clear the sites and build something entirely new. But Kraus, who had nearly a decade of experience restructuring failed real estate projects at Citicorp, understood that these old buildings have potential: he saw economic potential where others saw impediments to economic development. But, Kraus explained, it’s not just business: “I fell in love with old buildings when I was 10, and it’s stayed with me as a passion,” he said. “My mother was a preservationist. I do this in part because I love these buildings and all these stories.” When Kraus came to New Haven and learned about the factory, around 20 years ago, he saw similar potential. He found that the factory had both the right historical significance and physical dimensions to be his next project.

Back in the museum, Bischoff-Wurstle vouched for Kraus: “Bill’s not full of shit,” he said. And indeed, Kraus has probably been more committed to seeing the building through the next phase of its life than anyone else. After the death of their father, Tony Yagovane’s daughters sought Kraus’ advice in doing “artist live-work as an homage to [Yagovane].” Kraus described Yagovane as an “outgoing and fun kind of guy” who had been aiming to convert the building into something like artist live-work housing since the 1990s. Yagovane’s dream, and the work he’d started in 1980, was to create horizontally organized spaces cared for and lived in by artists free from institutional pressure and high rent. From the start, Kraus was a believer in preserving that legacy of the building as much as the building itself. Over the years, he’s tracked down the former residents of the factory to figure out coolness. Kraus is largely responsible for reconstructing its latter-day history based on the memories of the Yagovane children and on physical artifacts found in the building.

After determining that a redevelopment project was feasible, Kraus conducted a survey of artists to gauge interest in living in the converted factory. The survey, distributed by the Arts Council of Greater New Haven and the New England Foundation for the Arts, among others, received 300 respondents. Kraus called it the “biggest, most successful artist survey [he’d] ever done.”

When looking at the survey results, however, Kraus was surprised to find that only ⅓ of the respondents were artists of color in a city with a population that was ⅔ people of color. What Kraus found is that New Haven’s established arts institutions, often affiliated with Yale, were alienating to artists of color. “There really is a lot of racism in New Haven around arts and culture, which was a surprise to me because I had not encountered that elsewhere,” Kraus said. He envisioned targeted outreach to artists of color to secure housing for and promote visibility of the non-white arts scene in New Haven. The goal was for the area and its eventual residents to make themselves known as an alternative to the New Haven arts establishment. “No one,” Kraus said, “[would] ever…be able to say ‘we don’t know where the artists of color are.’” They would be in the factory.

To understand why people live where they do, it is helpful to look at histories of local development. The area around the clock factory didn’t used to be a distinct neighborhood. In the 19th century, Wooster Square was a broad term that included both sides of what is now I-91. The area around the central green, what we now call Wooster Square, was home to several businessmen and shop owners, including James English, a major financier of the clock factory. Wealthy and influential men like these lived in homes designed by prominent New Haven architects like Henry Austin. Because it was convenient to have labor near the factories, Italian and Irish immigrants were housed in the area when they came to New Haven. As wealthier residents moved away to escape what had become New Haven’s industrial center, Wooster Square transitioned into a fairly dense “little Italy.” By the mid-20th century, it retained its architectural heritage—but not the wealth that came with it. When urban renewal became the order of the day, highway construction was imagined as a way to connect New Haven to a new commercial network and to revitalize the city in the face of industrial collapse. Faced with this supposed imperative, New Haven had to decide: which areas would be sacrificed on the altar of economic progress? Where would the highway be built?

When the area was slated for clearance after World War II, residents began to organize around Wooster Square’s architectural heritage. In the late 1950s, Ted DeLauro (father of Congresswoman Rosa DeLauro) worked with Yale architecture students and the newly formed New Haven Preservation Trust to make a case for Wooster Square’s historical value. The NHPT succeeded in routing federal funding for urban renewal into home repair in Wooster Square. That is to say, “redevelopment” money that had for decades been used to clear housing was used to maintain and renew the older townhomes. The townhomes on the other side of I-91, as both Kraus and Bischoff-Wurstle said, were often no different from the majority of the ones in Wooster Square. In the 1971 form nominating Wooster Square for the National Register of Historic Places, the delightful homes on Court Street were described as “tenements which were the worst housing in the area.” But because wealth was inscribed architecturally in the homes of men like James English, the residents of Wooster Square were able to move the highway a few feet east, and spare their own neighborhood.

Because the homes on the wrong side of I-91 were razed, they never got the chance to become “historic.” While what gets deemed historic (as opposed to say, shabby and expendable) in the housing market has everything to do with profit, these designations emerge from a historical process that unfolds along class lines. If the exhibit and the documentary use the language of historical preservation, then, so too does the housing market. Pointing to a picture of the neighborhood around the clock factory before urban renewal, Bischoff-Wurstle identified a row of now-destroyed homes as a place that today would be deemed “historic” and make the landlord a pretty penny. “Who picks what a slum is?” Bischoff-Wurstle asked rhetorically. “The banks and the government do.”

This is a short and simplified version of events. It can be read as a victory: the Preservation Trust modeled the economic potential of saving rather than destroying old buildings. But ultimately, what was demolished and what survived is telling. “History” is associated with wealth. Historical preservation is also self-perpetuating: when Wooster Square was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1971, part of the reasoning named this very historical preservation effort as a reason Wooster Square was a historically significant place.

One of the only other things to survive the clearances of the 1950s and 1960s was a public housing development known as Farnam Courts. Farnam Courts was built by the then-newly established Housing Authority in the 1940s with money from the federal government. This form of public housing began “as a big housing production program post the world wars,” said Karen Dubois-Walton, the Executive Director of the Housing Authority. “It was supposed to be federally supported middle-income housing,” until the federal government shifted tactics and began pushing for suburban housing.

The result? What was at first a nominally racially integrated development with hot water and built-in community space saw its better-off (and often white) residents leave for West Haven and Hamden. The construction of the highway right next to Farnam cut it off from what had been its neighborhood and left it as some of the (if not the) only housing between I-91 and the Mill River. As the federal government pulled more and more money away from traditional public housing efforts like Farnam Courts, they fell further and further into disrepair. In 2012, the Housing Authority, through the nonprofit Glendower Group, relocated the residents and began tearing down Farnam Courts to rebuild it as the mixed-income Mill River Crossing.

Kraus argues that the practice of tearing down old buildings is counterproductive. Not only does it destroy something of historical value, it also stymies further economic growth. “These [historic] buildings are the engines of development,” he argued. In this sense too, Kraus is seeking to restore the factory—if its first life was as an industrial economic engine, its next one can be an economic engine as a housing development.

But Kraus’s vision of affordable housing for artists of color fell apart a few years ago, as Reed Community Development and its affiliated holding company, Taom Heritage New Haven LLC, began to neglect the site. A 2016 report found that the factory had unsafe levels of radium attributed to the paint used in wristwatches during the Walter Camp era. Connecticut’s Brownfield Municipal Grant program has set aside $700,000 for cleaning up the factory site. In 2018, the city of New Haven approved a redevelopment project with money for environmental cleanup and a tax abatement for construction, but since then, the city has claimed that Reed failed to pay what taxes it did owe and allowed the site to fall into further physical disrepair. In August of 2023, the city agreed to buy the foreclosed property from Taom Heritage.

Now, the city has passed the site to the Housing Authority of New Haven, which is hoping to recover the site with “most of the remediation done.” Karen Dubois-Walton, Executive Director of the HANH, is eyeing the site for conversion into up to 100 units of mixed-income housing. Dubois-Walton explained that the present-day model of housing began in the late 1990s with the demolition of Elm Haven, then the oldest public housing development in the city. Elm Haven was replaced by Monterey Place, a mix of market-rate, partially subsidized, and low-income housing.

This mixing, Dubois-Walton said, creates “more vibrant” communities and “doesn’t just segregate poverty” in the same way traditional low-income housing like Elm Haven and Farnam Courts does. Crucially, mixed-income housing is easier to get funding for. “Lower income public housing ties the Housing Authority’s hands on funding,” she added, noting that you can’t raise capital via federally backed mortgages for these developments—the federal government will not back projects that are composed solely of affordable housing.

In an astonishing reversal from the urban renewal period that saw highway construction and home demolition as an economic winner, today’s vision casts housing as the catalyst for community development and economic growth. Dubois-Walton described the process as a sort of spillover effect—when housing gets built, it can “spark and spiral out and pull in other investments,” according to her. The clock factory site sits diagonally across from Mill River Crossing, a 2018 HANH development of just under 100 units-cum-retail space. Dubois-Walton is hopeful that connecting the new factory housing with the existing Mill River Crossing can create “synergy” and turn “one product into so much more.”

New Haven needs more housing—according to Dubois-Walton, the city faces a severe “underproduction of units”—but the institutionalization of housing and its centralization under a government agency seems to run counter to the ethos that Yagovane and then Kraus sought to implement. Instead, issues of plausibility and financing dominate discussions and low-income housing tax credits and historic restoration tax credits cover the costs. Kraus admits that if he “could have waved a magic wand, what he would have liked to do, what the family would have liked to do, is create artist condominiums…and sell them so it really belongs to the artists.” But we’re short on magic wands, and so all that’s left of the vision is “millions and millions of dollars” in the red column on the balance sheet. If the “dream” was artist-owned co-op-style housing, it was always, given the need to create a well-financed sustainable project at-cost, impossible.

At this point, everyone’s hoping the building stays standing. “Time beats the hell out of these things,” Bischoff-Wurstle said, and he’s right. Parts of the building that were functioning businesses five years ago are now crumbling brick walls with giant holes. The building has survived improbably, impossibly, even when there was no one to defend it. The factory, as both Kraus and Bischoff-Wurstle have it, played host to the best days of some people’s lives. The latter spoke bleakly of what he called the “ouroboros,” the snake eating its own tail, the process by which coolness springs up in shady places, hidden from power—only to be consumed by wealth, time and time again.

Separating history from wealth is a difficult task. But for Bischoff-Wurstle, that’s the point. The factory is a weird, skeevy, unsanitized place, a “place of innovation and fermentation,” and it is that spirit of innovation and irregularity he wants to preserve. It is the spirit of hiding the bed in the wall when the fire marshal comes by because you couldn’t have residences in an industrially zoned area. It is the spirit of being able to make art without worrying about paying the bills: as Bischoff-Wurstle said, “New Haven has been called the cultural capital of Connecticut. If people can’t afford to do culture, what are we?” It is a spirit of youthfulness, instability, care, and spontaneity. But all of those things, at least in the context of the factory, are history now.