YNHH’s Smilow Cancer Hospital pioneers new radiotherapy technology

The machine, created by biotechnology startup RefleXion, is the first of its kind to combine PET imaging and radiotherapy for use against solid tumors.

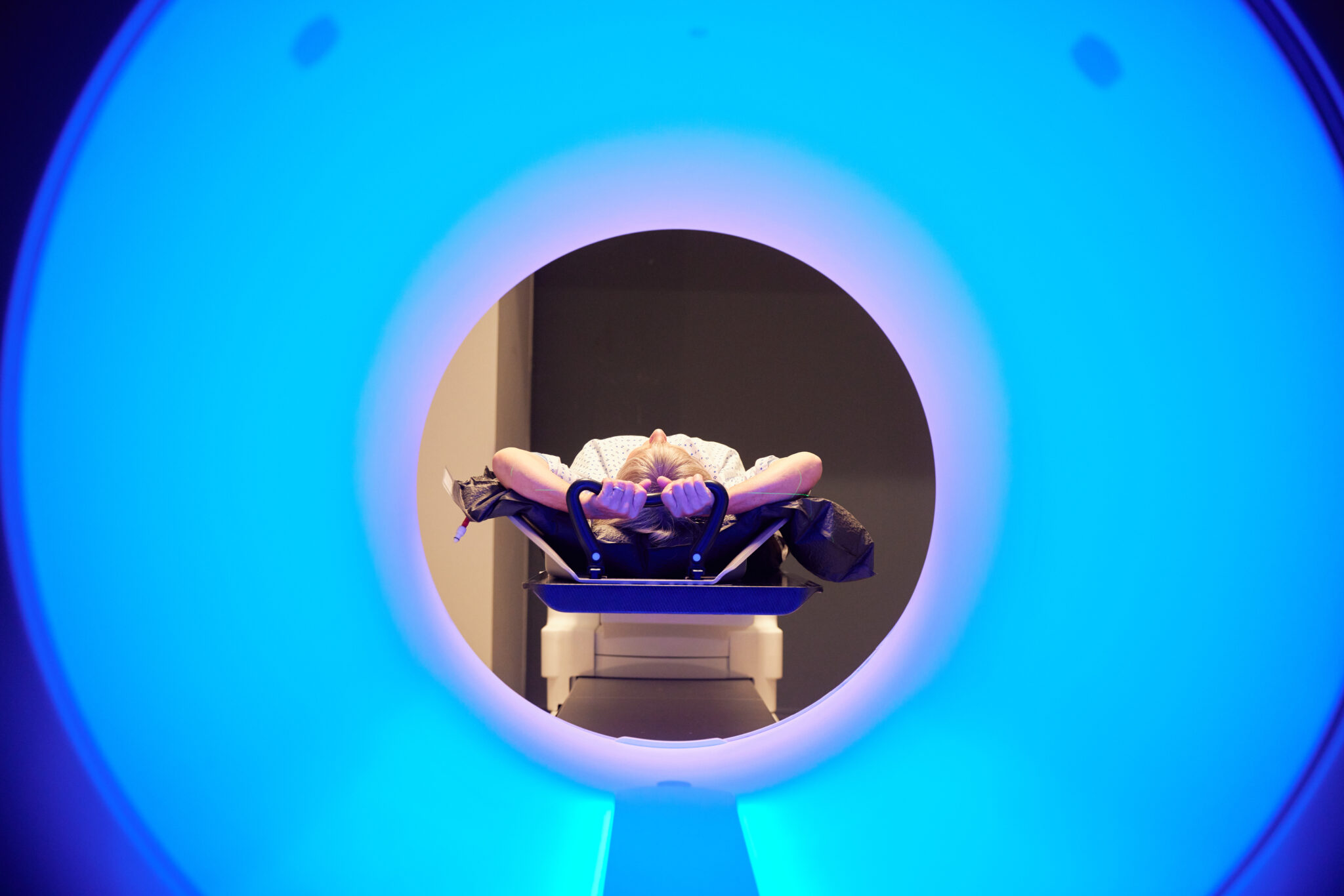

Courtesy of RefleXion Colored Beauty

Yale-New Haven Health’s Smilow Cancer Hospital is one of the nation’s first to install a machine which can target and treat solid cancer tumors in real-time.

Called RefleXion X1, this technology combines positron emission tomography, or PET scanning and radiation therapy in a novel treatment called SCINTIX. It was cleared by the FDA for clinical use against bone and lung metastatic cancers — tumors which have traveled beyond their location of origin — in late February, showing promise in the fight against late-stage cancers. While the machine is currently being vetted and checked for quality, Smilow staff look forward to treating their first patients with this technology by April.

“We are trying to test whether this technology will make it easier, safer and more effective in treating lung and bone tumors,” Henry Park, associate professor of therapeutic radiology and chief of the thoracic radiotherapy program, wrote to the News. “Especially for patients with metastatic disease, but also for those with earlier-stage disease.

Cancer clinics have long used radiotherapy — a treatment that uses ionizing radiation to kill harmful cells — but the strategy is not without drawbacks. The biggest challenge of radiotherapy is targeting lethal radiation to malignant cells while ensuring protection of normal body cells.

Though PET scans, which visualize a tumor’s location, have helped hone radiotherapy targeting, they take far too long to generate an image, according to RefleXion cofounder and chief technology officer Samuel Mazin. Tumors are not stationary, moving with a patient’s breathing, digestion and other bodily motions. In the minutes it takes to generate a PET scan, a tumor may have already shifted away from its original location. This results in a “collateral damage,” as Mazin described it, that can increase the toxicity of treatment.

“Imagine if the tumor was like a car on a racetrack,” Mazin said. “[You can] basically illuminate the entire racetrack to make sure that you’re always hitting the car… but you are also getting a lot of other stuff that you don’t want to hit.”

Though Mazin was compelled by the idea of PET imaging, he hoped to make it occur faster. He wondered if he could target the earliest clusters of PET signals, which are emitted by radio-labeled glucose taken up by fast-metabolizing cancer cells, before they have rendered a final image. This could occur on the order of milliseconds, allowing radiation to be delivered almost in real-time.

“When this idea popped in my head, it all of a sudden shifted my whole life,” Mazin said. “I could do nothing else but think about it.”

The query propelled him out of academia, where he had been working as a postdoctoral researcher at Stanford, and into the realm of biotechnology. He co-founded RefleXion in 2009.

The SCINTIX treatment, which was pioneered by RefleXion, combines PET imaging with radiation delivery. A patient lies down in the Reflexion X1 device, which rotates around them rapidly at one revolution per second to collect PET signals while shooting radiation beams along the same path. The company and machine are named after this idea of “reflecting” radiation toward its point of origin.

“You just really want these signals to turn tumors into their own beacons, their own kind of active transponders,” Mazin said.

Such precision will allow SCINTIX to be used safely alongside other cancer therapies. Both Mazin and Sean Shirvani, chief medical officer at RefleXion, expressed interest in combining the treatment with other whole-body therapies like surgery, chemotherapy and immunotherapy.

These combinations can be dangerous without advanced radiation technology, said Shirvani, especially when treating multiple tumors in a patient’s body.

“In [this] case, you really want to be very accurate, so that the patient doesn’t have too much toxicity preventing things like drug therapy, chemotherapy, and immunotherapy from being part of the dance,” Shirvani wrote in a statement to the News. “With SCINTIX, we use the tumor to guide its own treatment, thereby hopefully achieving that precision that then opens the way to safe and effective combinations with other cancer therapies.

Now that RefleXion has been cleared by the FDA for clinical use, the Smilow Cancer Hospital looks forward to its implementation. Park hopes the technology will make it easier to treat patients with multiple tumors, or those in the later stages of lung or bone cancer. He expressed his wish that such patients will experience improved quality-of-life, alleviated side effects and more effective disease control following their treatment.

Park is also hoping to create a registry which will capture patients’ data for their treatment with the machine. He alluded to several clinical trials, involving existing and novel radiotracers, which can be tested in conjunction with SCINTIX. He emphasized that implementing the machine will require time and adjustment, but he hopes to find how to “most optimally harness the power of the technology.”

“Using SCINTIX is certainly expected to slow down the workflow, especially in the beginning,” Park wrote. “However, we believe that this is very much worth it in order to offer our patients such a novel tool to treat their cancers.”

So far, the technology has only been approved for lung and bone cancers, though Mazin is optimistic about expanding RefleXion into a general cancer treatment device. He envisioned it being able to “treat almost every solid tumor case and cancer at any stage.”

Mazin also mentioned trying to implement SCINTIX at the community level, beyond large healthcare systems like YNHH. He noted the economic challenges that accompanied making SCINTIX accessible and appealing to such cancer centers, however, and declined to answer if RefleXion would cut costs to improve access for community-based clinics.

“We’re always looking to make it work with every center,” Mazin said. “And so, we’ll just leave it at that, because it’s a really complex project to get these machines installed in sites.”

Smilow Cancer Hospital is the only National Cancer Institute-designated comprehensive cancer center in Connecticut.