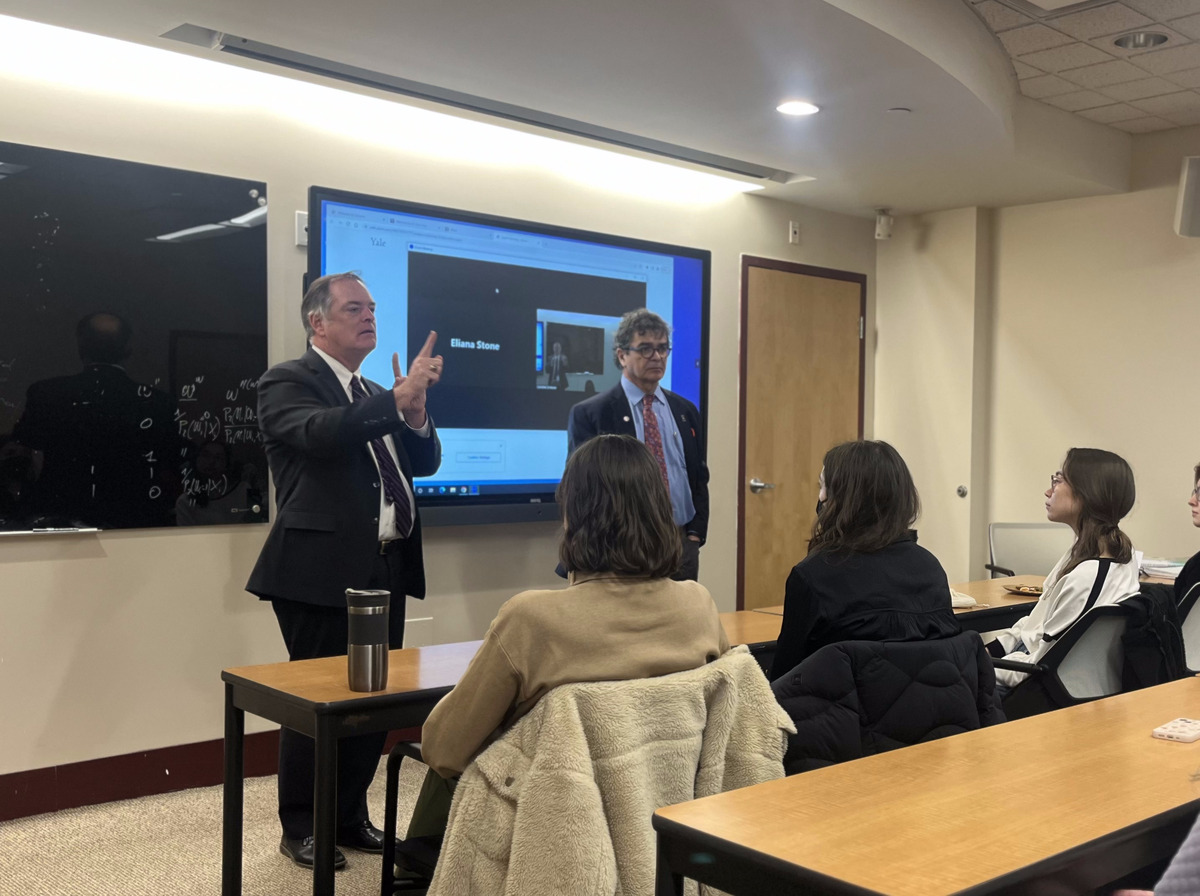

Famed “forever chemicals” lawyer Robert Bilott talks PFAS and policy at Yale

Nearly all people in the United States have PFAS in their blood. Attorney Robert Bilott — famous for revealing a decades-long record of toxic PFAS chemical exposure by the DuPont company — spoke on the importance of effective communication in translating scientific research into legislation.

Kayla Yup, Contributing Photographer

Wilbur Earl Tennant’s cattle were dying. It was 1998 when the farmer from West Virginia first approached environmental attorney Robert Bilott for help.

Bilott hesitated. As a corporate defense attorney of eight years, Bilott didn’t sue chemical giants — he represented them. But the situation was suspect. Diving into Tennant’s evidence, Bilott uncovered a tale of corporate corruption and its hazardous consequences. In a class action lawsuit against chemical company DuPont, Bilott represented 70,000 people whose drinking water had been contaminated with PFOA, a toxic chemical used to produce Teflon chemical coating. Perfluorooctanoic acid, or PFOA, is a man-made chemical used in non-stick and stain-resistant goods, from non-stick pans to fire-fighting foam.

Not only were Tennant’s cattle drinking contaminated water, but the health of the West Virginia town’s residents was being endangered. Bilott ultimately secured a $671 million settlement for residents who developed kidney and testicular cancer from drinking the contaminated water. But when Bilott first filed the lawsuit, the Environmental Protection Agency was not even aware that PFOA was hazardous. Despite DuPont knowing of the risk as early as the 1970s, that information was hidden. It was not communicated to the regulators who could take action.

“It’s critically important that people be able to get outside of their little silos,” Bilott said. “When I started my work, I was focused on what lawyers are supposed to do, and we’re supposed to lay this all out in a legal brief … but it’s going into a court where it’s all being presented in legalese with case citations, and nobody else is reading any of that or paying any attention to it.”

Bilott, who became a lecturer at the Yale School of Public Health in 2021, wants to help public health students translate their work to the “real world” and defend against exposure to toxic chemicals. On Feb. 24, Bilott lectured and had lunch with students in a YSPH course called “Public Health Toxicology.” In his current role, Bilott also advises MPH and doctoral students in the Environmental Health Sciences department.

PFOA belongs to a larger class of chemicals called perfluoroalkyl substances, PFAS. Dubbed “forever chemicals,” PFAS compounds have a strong carbon-fluorine chain which makes breaking down the chemical challenging. However, that persistence also enables its favorable properties — PFAS are hydrophobic, allowing them to repel water and other liquids. This makes the chemicals effective for use in nonstick pans and firefighter foam, but near-impossible to eliminate fully from the environment or the human body.

According to a study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 97 percent of people in the United States have PFAS in their blood.

In August 2022, 23 years after Bilott filed the lawsuit against DuPont, EPA proposed to designate two chemicals of the PFAS class as hazardous. Bilott hopes students learn from his decades-long battle against DuPont and find a way to communicate public health information effectively across different fields.

“He really is a pioneer of protecting public health,” said Vasilis Vasiliou, professor of the toxicology course and chair of the YSPH department of environmental health sciences. “All his work has caused awareness, globally, regarding these compounds and how this could be harmful to human health.”

When Bilott realized that regulators had “no idea” that PFAS were hazardous, he knew he had to translate his “legalese.” Digging further, he found that the scientific world was working on the same issues as he was, but “in their own little world” — much of which was not being translated back to lawyers or regulators. Bilott said that the research on PFAS was generally only presented in long scientific articles with dataset analyses of p-values and concepts that were foreign to lawyers.

Bilott spoke to students about the need to translate the science behind public health threats to not only the people exposed, but to the legal and regulatory spheres.

In the courts, the judges and the lawyers need to know why something is toxic, he said. Regulators who develop the appropriate safety guidelines and standards for chemicals, along with policymakers, need to understand the significance of that health threat.

“You have to be able to not create a panic to the public, but also explain,” Bilott told students.

During the PFAS lawsuit, Bilott realized his ultimate goal was to translate scientific information to the public. As media outlets started covering the legal battle, Bilott recognized the power of conveying this public health crisis to the people.

In 2019, the film “Dark Waters,” which depicted the battle against DuPont with Mark Ruffalo playing Bilott, was released to widespread media attention.

“Now what we’re seeing is this group of chemicals that nobody could understand or pronounce or say, people are now talking about regulating them,” Bilott said. “The EU is going to completely ban them now. The president of the United States is talking about this now. So it works and it could be something that has dramatic consequences.”

Many of the students’ questions surrounded how chemicals are produced and made available to the public. Students wondered how regulatory policies could be improved to protect human health, and what role public health professionals could play.

Vasiliou said he plans to propose a new YSPH class on how research can be translated to regulatory policy through effective science communication. He believes Bilott will make the department’s curriculum “more transformative” using his background in science communication and regulatory policies for the environmental health sciences.

For Clare Loughlin SPH ’24, a first-year master’s of public health student, Bilott being a guest lecturer was a huge factor in her decision to come to YSPH. She said she hopes to study PFAS contamination and climate change.

Loughlin heard Bilott speak at a conference in 2017, which she said “completely just changed [her] life.” She ended up working on a community project in Merrimack, New Hampshire, where she went door-to-door asking people to fill out a health survey. The community had been unknowingly drinking water contaminated with PFAS for over 20 years.

“I was meeting people who said, ‘What do you mean my water is contaminated? I just moved here’ or ‘I have young kids’ or ‘My whole family has cancer,’” Loughlin said. “That was really emotional and I felt committed to studying PFAS for my career.”

Loughlin said she enjoyed learning about Billot’s vision for cleaning PFAS from drinking water and other environmental sources of exposure. She is interested in remediating PFAS from the environment and our bodies and pursuing justice for communities facing contamination.

“He wanted to inspire us to be persistently curious and follow the science,” Loughlin said. “There’s so much work to be done … and we are grateful to be in the fight with other people who are so thoughtful, willing to come speak with students, speak with community members [and] communicate through film, through books, through articles [to] get the message out because we’re all contaminated by PFAS.”

Bilott’s battle against PFAS continues: now representing states all over the US, Bilott is trying to ensure that the people responsible for state water supplies with PFAS are held accountable. He doesn’t want costs of cleaning the water to get pushed down to “the victims,” he said, including city and county governments and taxpayers.

Bilott also wants companies to pay for the studies on the dangers of PFAS. The only way to establish policies regulating PFAS is to prove its toxicity through scientific studies.

Without them, companies producing PFAS can continue to claim that the toxicity has not been proven yet.

“Right now, [chemical companies] are sitting back saying ‘there’s no evidence,’ which the public interprets as meaning studies have been done and it’s been proven to be safe,” Bilott said. “But no. ‘No evidence’ means ‘we’re not doing the studies.’”

Amid these health concerns, the PFAS class continues to grow, as second-generation PFAS with different carbon chain lengths are developed. Despite PFAS being “one of the most comprehensively studied chemicals ever,” said Bilott, chemical companies have created a game of “Whac-A-Mole.”

As companies design new PFAS compounds, scientists must rush to study them all, he said. Bilott hopes to create a mechanism to have these studies done without the federal government having to pay for them — this cost, he believes, should fall on the companies at fault.

Yale School of Public Health is located at 60 College St, New Haven, CT.