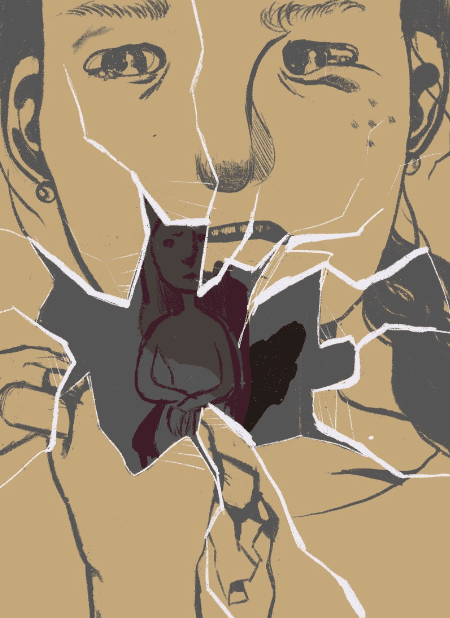

Illustration by Ariel Kim

Nine years ago, I missed the health class where they split up fifth grade girls and boys for the puberty talk. I was busy volunteering at field day, picking up plastic cones and ushering small kids around. I unfortunately never made that class up. But it would have been my only opportunity to talk about those things with an adult. In many Asian families, the birds-and-the-bees and other women’s health topics aren’t really up for discussion.

I’ve seen “the talk” on TV, but I’ve never heard of an Asian parent giving one. To be clear, this is not a scientifically robust observation — I’m sure there are outlier Asian parents who talk about sex with their kids freely. But that is overwhelmingly not the case. Though the silence often comes from a place of protection and love, the stigma around women’s health is frankly outdated.

It’s hard to become a woman, but even harder when shame and secrecy surround it. In this generational cycle, the potential for inherited wisdom evaporates in place of stigma-laden silence.

I spoke to women from a range of Asian backgrounds to compare our lived experiences and start (finally) opening up conversations.

Menarche: the start of it all

Girls typically get their first menstrual period — called ‘menarche’ — between ten and fifteen years old. It’s the first sign of womanhood as hormones hijack the body. Nikita Paudel ’25 described her first period as “very traumatic.”

“What I understood when I was a child was that when you get your period, you kind of don’t really have your freedom anymore because bad men, bad people can abuse you and you can become pregnant,” Paudel said. “I vividly remember not wanting to have my period because I was afraid that my freedom would be stripped from me.”

That’s what she understood from family and the general chatter around periods in her Nepali culture. Paudel, like me, attended Baltimore County public schools, so she said she also had the “little course” in elementary school where they give you deodorant and explain what a period is biologically. But she recalled still not fully understanding what it meant “socially” to have a period.

From a young age, Paudel noticed the taboo and shame that came with menstruation, “at least in [her] Nepali household.” Her period came when she was 11. Unsure if it was her period or not, she showed the stain to her mother.

“I kind of remembered seeing an angry or disappointed face on my mom’s face,” Paudel said. “And I started bawling my eyes out in front of her, just realizing that like, ‘Oh, I don’t know, is my mom disappointed in me?’ I was just confused.”

Paudel said that in the western parts of Nepal, there is a practice called “Chhaupadi,” which restricts a woman’s activity while on their period. The most extreme versions involve sending women to an outside hut. According to the UN, the practice continues, perpetuated by myths surrounding menstruation, even though the Supreme Court of Nepal banned chhaupadi in 2005.

Though Chhaupadi is technically banned, Paudel noted that some of those practices and the stigma that surrounds menstruation “still linger on.”

For the first couple days of her period, she was not allowed to eat at the family table, come into the kitchen, or go near the prayer room. For around three days, she tried to follow these rules, until her dad interjected and said, “At that point, why don’t you just throw her out?”

Paudel said that at age 11 and through high school, she would have interpreted her mother’s reaction to her first period as “disappointment.” But at 20 years old, knowing her mother better now, she would say her mother was more “scared” than anything.

“Because now, I am going into a different phase of my life where people can hurt me,” Paudel said. “And my body changing and me turning into a woman, I think that had a lot more to do with it than disappointment […] Upon a lot of reflection, I do think it was just her being worried or her not fully understanding what was going to happen.”

Paudel noted that taboo around menstruation is seen around the world, but she suspects it to be “more concentrated” within Asian families and immigrant families in general. She compared it to topics such as mental health, which aren’t really discussed among immigrant families.

But things have gotten “much better” since, Paudel said, and menstruation is no longer a taboo in her house. She found that living in America influenced her parents’ thinking, in terms of understanding of what it means to be on your period.

Ngọc-Lynn ’25, who is Vietnamese American, and Ariel Kim ’25, who is Korean American, both said that periods are considered “natural” and “normal” things to talk about in their households. However, Kim mentioned that it is considered good “manners” to hide menstrual products, such as by wrapping a pad in toilet paper when throwing it out, so that others can’t tell when you’re menstruating. Aeka Guru ’25, who lives in India, said that when someone buys a menstrual product, it’s often wrapped in newspaper or an opaque black bag. Across different Asian cultures, there seems to be a sense of wanting to hide when you’re on your period due to stigma.

Karley Yung ’25, who is Chinese American and the president of the menstrual equity group YaleBleeds, connected the stigma surrounding women’s health in Asian cultures to women still being seen as “the inferior gender” whose issues are “not considered worthwhile” to discuss. Her experience with menstruation was speaking about it in hushed voices and hiding her pads.

“It took an incredible amount of convincing for my mom to get me tampons and let me eventually use a menstrual cup, given the stigma and ‘relationship’ of using internally inserted menstrual products with virginity,” Yung said. “I found this to be very frustrating.”

Guru said that her household is a little more progressive, in terms of her talking openly about her period with her parents. She also brought up how in her culture, there is a religious ritual conducted when a girl gets her first period. It’s a beautiful celebration of a girl becoming a woman, that gathers the whole family to give you gifts and to throw rice and flowers on you. Guru sees progress in breaking down the taboo around menstruation — some companies in India are even offering period leave.

“But I still think just in general, becoming a woman is really difficult,” Guru said. “Especially in households where even some mothers may not feel comfortable talking about their own lives, it could be difficult for daughters because they feel like they don’t have an ally.”

Menarche is the first step in becoming a woman, and the silence around it foreshadows the greater shroud of mystery around women’s health topics in Asian families.

So you want to get on birth control?

Paudel’s best friend from home used to throw up every time she had her period. So, the friend’s parents, who are white American, got her on birth control when she was around 11, and that was that. But when Paudel started having symptoms “degradative” to her health, she knew it would not be the same for her.

In her junior year of high school, Paudel had to be taken to the nurse’s office because she almost fainted from the severity of her period symptoms. Her doctor agreed that birth control would be a suitable next step for managing her symptoms. But Paudel’s family was very hesitant..

“Why do we need to be on it? This is for grown women, this isn’t for kids like you,” Paudel recalled her mother saying to her.

The general sense was that the only reason to use birth control was to prevent birth, Paudel said. According to her, there is plenty of misinformation around birth control within Asia. Common concerns are that birth control causes infertility, or that birth control is only an excuse to have sex.

Though Paudel eventually convinced her mother to let her get birth control, she noted that many of her Asian friends have had to do “some crazy things” to get birth control. One friend tried going to her doctor to get birth control confidentially, but the insurance bill was sent to her home, landing her in trouble.

Yung had a similar experience. In her Asian household, discussion of birth control as a method to control heavy or painful periods gets shut down, as it would be “unnatural.”

Huynh said that there is often an educational barrier when it comes to Asian parents’ understanding of birth control. Her parents did not have sex education in Vietnam, and they grew up in a time when birth control was not common or accessible. This makes birth control a more taboo topic.

In my women’s health seminar this week, our guest speaker said “the pill” freed women from the chains of their biology. Likewise, Asian friends have expressed to me that their parents should be happy they were “being safe,” but the stigma is pervasive. Even when away at college, the newfound independence and bodily autonomy comes with anxiety you can’t seem to outgrow.

I asked Guru, who has experience in educating on sexual health-related issues, for advice on asking Asian parents for permission to get on birth control. Her personal advice was to demonstrate to parents that you’ve done your research on birth control, including potential side effects and risks, and emphasize that you want the kind of relationship that enables open conversations.

I still could not imagine asking my parents for birth control. But I agree with Guru that most Asian parent-child relationships do not enable talk about contraception and sex. And to me, that’s dangerous.

If you’re not giving me ‘the talk,’ who will?

When you ask an Asian parent where you came from, a common joking response is “we found you in the trash.” For Huynh, this answer represents the greater mystery around sex education and women’s health topics in Asian families.

Huynh mainly relied on her older sister to teach her about periods. But when it came to birth control and sex, even her sister didn’t want to discuss it for fear of encouraging sexual activity.

The problem is that a parent, armed with the wisdom of lived experience, is naturally the best guide for a child. However, in Asian families, when mothers can go as far as to cover their child’s eyes during kissing scenes in movies, physical affection is not so normalized.

Paudel never saw people kiss in South Asian media during her childhood, whereas she had heard of non-Asian friends watching sex scenes (embedded in Western movies/TV) with their family.

“As an Asian woman, college comes with a lot of unlearning and relearning what sex is and how to talk about it,” Guru said.

It was “nerve-wracking” and a bit “crazy” for Guru to see sex talked about during first-year workshops with CCEs. She could not believe that there were condoms openly on display in laundry rooms. But she eventually became more comfortable. When Guru told her parents she became a CCE, they were surprised at how okay people were with talking about sex. Guru has made an effort to talk to her family more about the sex-positive culture here. Now they’re a “bit more open” to it, though she said they probably see her more as adjacent to the culture or “at least watching it” then involved in it.

Guru emphasized that immigrant parents who did not go to college in America may assume that the often sexualized depictions of college life in TV shows and movies mirror reality. Guru has not “had those conversations” with her parents yet. She thinks it is better to try “chipping away” rather than “shattering” their norms when it comes to sex. One day, maybe you could even ask about a parent’s first time and advice for safe communication surrounding sex — but that takes time.

If you don’t get the talk, your ideals and norms of sex may not be realistic, Guru said. It may come from the movies or porn, which contain behavior that is not always healthy and shouldn’t be emulated. Even peers may have misconceptions when it comes to ideals for sex, so talking to them isn’t always the best resort.

Huynh found it comforting to go through the Communication and Consent workshop as a first-year, since most conversations she had around sex and consent beforehand were from the internet.

“It was affirming in a way,” Huynh said. “It felt like we were all on the same page, and we all agree that this is how it should be. I can’t believe it took me till I was 18 to have this talk. I wish I could have had this when I was younger.”

She said sex education provides important knowledge about consent and healthy conversations — whether you are currently sexually active or not.

“We rarely talked about sex explicitly in my family, and when we did, it was only spoken about in a way that told me that sex was only for procreation,” Yung said. “At no point was pleasure or intimacy discussed; in fact, I was taught that as a woman, it was supposed to be painful but something I needed to do to have kids.”

Huynh noted the nuance of growing up with two different cultures as Asian American women. One culture may be “telling you not to talk about this” while another is saying “speak out, learn about this.” Parents who grew up in Asia may not understand that experience, growing up in a time where hypersexualization happens at a young age, Huynh said. She recounted already being insecure about her body in fifth grade.

To Huynh, in the age of social media it feels “almost inevitable” that children will find out about sex. It’s either internet sludge or a mature adult to guide a child through this phase of life.

Breaking the cycle

Though the job of raising a girl into womanhood should fall on both parents, a mother is a daughter’s natural role model and mirror. And if we’ve learned anything from the Oscar-winning Everything Everywhere All at Once, it’s the complexity of mother-daughter relationships in Asian culture. It’s hard to judge our moms for their silence or their perpetuation of stigma because they too endured it all.

“My mom also had a very, very rough coming of age into womanhood,” Paudel said. “And I didn’t really fully understand her story. At the end of the day, she went through her own struggles and battles to get where she is today. While it would have been nice to have been able to talk about it, I also fully understand if she was not ready to unpack her own trauma coming into those conversations.”

Paudel said that if she ever has a daughter, she hopes to be a resource for her.

Huynh also wants to break these cycles of silence, and personally show her kids how to go about things safely and feel supported.

“My parents have been through so much, especially as refugees,” Huynh said. “But they just keep going and they don’t look at the past. I think that that’s why conversations about women’s health are still taboo, because there is a very dark history behind it.”

Huynh’s mother had her older sister at a young age, around 19.

“She has told me like nothing about it,” Huynh said. “She’s never warned me about getting married, having kids younger — she never warned me against that either. That’s like a part of her life that she just does not talk about.”

I also only have a fragmented understanding of my mother’s upbringing. I know she was the youngest of seven daughters, and that she wore high heels while waitressing. I know she once had the “perfect golden tan” when she was ten, and now the sun just burns her. But when I ask her deeper questions, she often acts as if her history were irrelevant to me.

Our mothers had to become women once too. It’s not fair to blame our mothers for deeply-entrenched cultural stigmas around womanhood that they too are confronted with. And it’s too late to be raised any differently. So, perhaps the most important part of opening up these conversations about Asian womanhood, is learning who our mother was before she was our mother. What did becoming a woman mean to her?

Moreover, what did becoming a woman mean to you?

The cycle ends with us. Let’s talk.