Yale researchers study gaps in the world’s biodiversity maps

In a recent study, Yale researchers identified how well the world’s biodiversity is documented in various regions. Filling these data gaps will aid in future environmental conservation efforts.

Anasthasia Shilov, Illustrations Editor

In an attempt to protect global biodiversity, Yale researchers have devised a framework that will identify data gaps in the world’s biodiversity maps that currently limit conservation efforts.

As researchers attempt to develop strategies for protecting biodiversity across the globe, there are some areas whose species have not been thoroughly studied, which hinder scientists ability to protect them. In response to this, Walter Jetz, principal investigator at the Yale Center for Biodiversity and Global Change — alongside Ruth Oliver, an associate research assistant at the center, and other colleagues — has created a framework to help identify the areas that need additional monitoring.

“I think the main message for us is that we’re really hoping that [this framework] can help researchers and practitioners best leverage the resources we have to improve our understanding of biodiversity,” Oliver told the News.

The study with which the framework was developed relied on data collected from amateur, or “citizen” scientists, and expert researchers. This data can be found in the Global Biodiversity Information Facility, which contains over 1.6 billion species sighting records. The citizen scientists contribute to data collection by taking pictures and submitting their sightings of certain species to the GBIF.

To place species population records in the necessary context for analysis, the team developed two metrics. Oliver explained that one assesses taxonomic and spatial coverage, which describes how well global biodiversity data for a given species in an area accurately represents the species’ expected range. The second metric looks at the sampling effectiveness of the data, and eliminates any duplicate records in well-populated areas where there tends to be superfluous data coverage for a given species.

Even though GBIF granted the team access to ample records, it provided them with little information that would translate into an effective spatial biodiversity knowledge base because records are highly redundant and only cover a limited number of regions and species, according to the paper. These gaps have been attributed to poor geographical access, availability of local funding and participation in data-sharing networks.

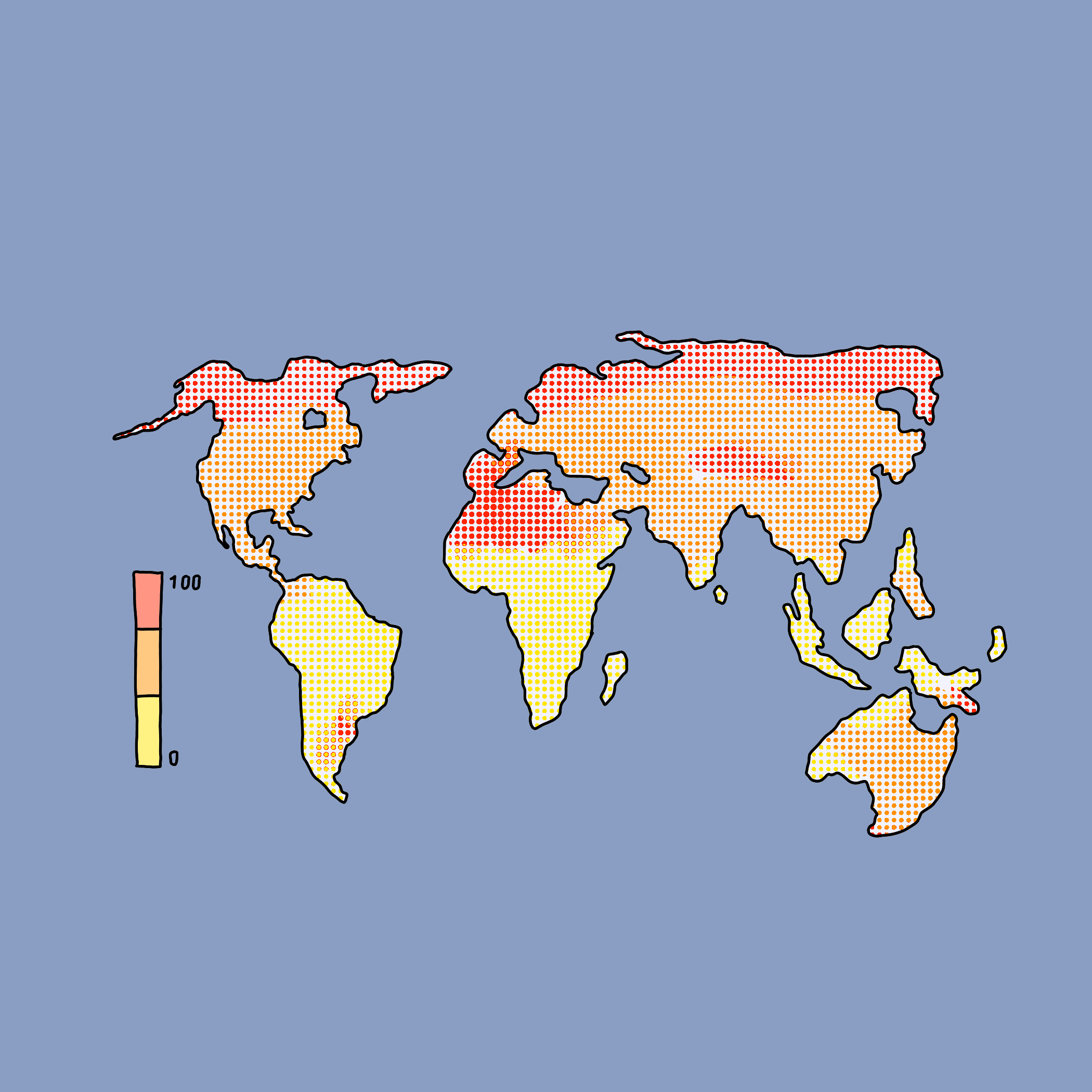

Oliver explained many of these gaps fall within historical inequities. The biodiversity in wealthier regions, especially in the Northern Hemisphere, is much better sampled than other regions of the world, such as South America and Africa. She highlighted that these gaps are especially unfortunate because these undersampled areas tend to have the greatest biodiversity.

“We hope that better knowledge helps us protect biodiversity better,” Oliver said. “One of the metrics in particular is supporting the UN Convention on Biological Diversity and the goal there is to help support targets to make sure that we’re acting in a way that best safeguards biodiversity for future generations.”

Oliver told the News that she faced some challenges in the development of the framework. She explained that since the team was working with over a billion biodiversity records it was difficult to integrate the data into the framework, which made it difficult to handle computationally. Ultimately, the framework she created made this integration process easier for future research and allows for additional updates to be input as new data is gathered.

This research focused on all terrestrial vertebrates, including birds, mammals, amphibians and reptiles, but according to Oliver, there are efforts to expand the work to marine species, insects and plants.

Jetz explained that the team’s ability to monitor biodiversity trends will be critical in supporting a “sustainable future in harmony with nature.”

“We show that significant gaps remain in our capture of biodiversity status and trends that have the potential to severely impact our ability to responsibly manage our planet,” Jetz wrote in an email to the News. “But on the flipside, by documenting these gaps and offering up tools to explore them we can transform them into opportunities for more effective biodiversity monitoring.”

The study was published on Aug. 12 in the journal PLOS Biology.