Yale researchers discover new treatment for babesiosis

A novel combination therapy shows promising signs to combat the tick-borne disease.

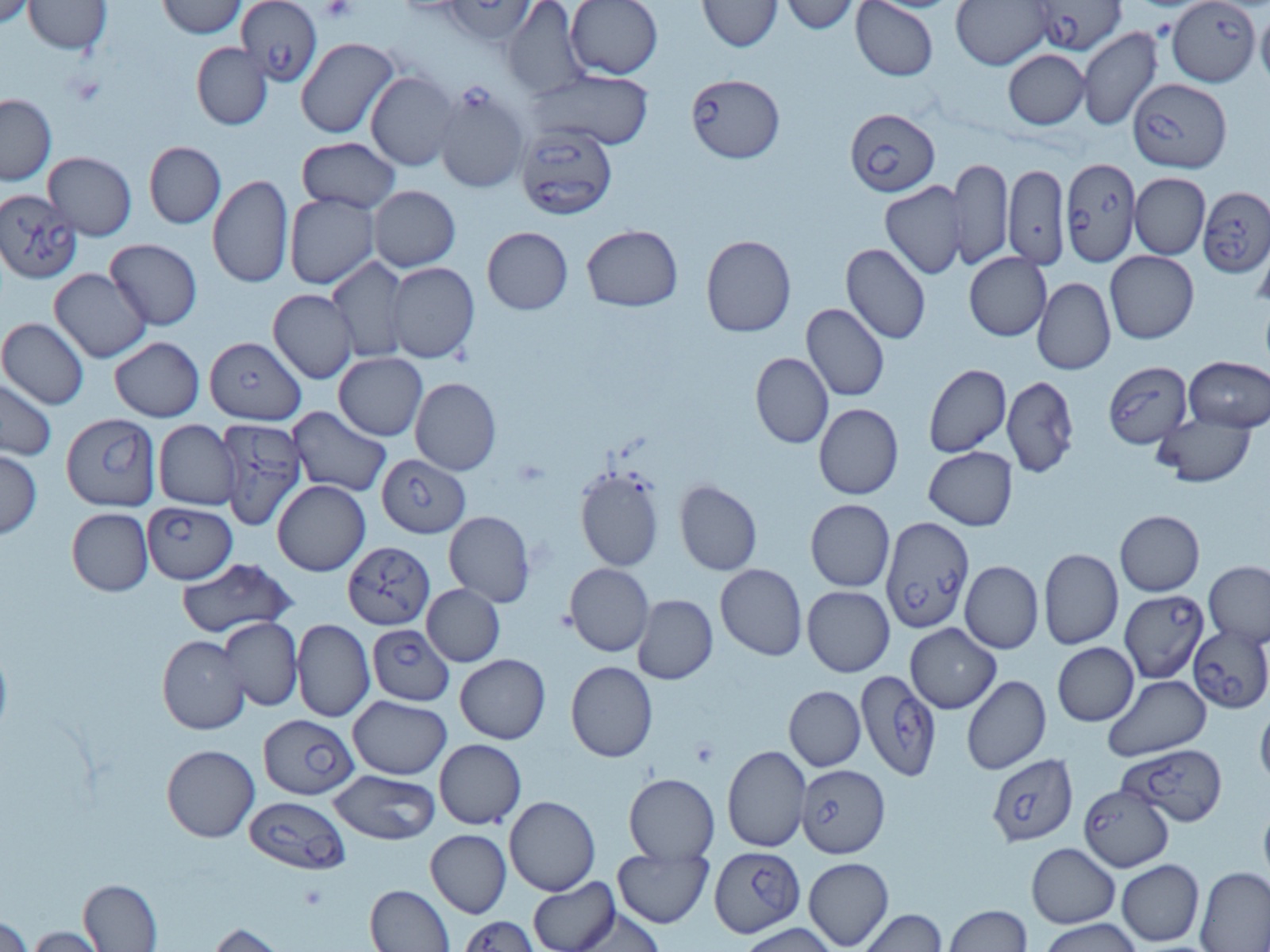

Courtesy of Pratap Vydyam

In a recent study, Yale researchers discovered a new way to treat the tick-borne disease babesiosis using a combination of drugs.

Led by Pratap Vydyam, a postdoctoral associate who studies infection biology, and Choukri Ben Mamoun, a professor at the School of Medicine and an infectious disease specialist, used a technique called combination therapy to merge the antimalarial drug tafenoquine with the antifungal drug atovaquone. After re-exposing the parasite to immunocompromised mice, the researchers found that mice treated with both drugs were cured of infection and exhibited high antibodies in their blood against Babesia parasites.

“This specific combination has the advantage of what’s referred to in drug discovery as repurposing,” Vydyam said. “Both drugs in this combination are already approved for treatment of various diseases.”

Babesiosis is a rare, though sometimes severe, disease that develops when microscopic parasites from a tick bite infect human blood cells. Most prevalent in New England and the northern Midwest, it is often treated with antimalarial and antiparasitic drugs.

However, new Babesia parasite strains have recently emerged and proved resistant to existing treatments, inspiring Vydyam and Mamoun to research new drug combinations.

“The currently approved treatments, clindamycin and quinine for severe disease and atovaquone and azithromycin for mild disease, do not perform very well,” Vydyam said. “Some patients fail therapy and the rate of relapse can be very high in some cases.”

Vydyam and Mamoun then conducted experiments on mice, hoping to use them as a model for how the parasite impacts humans.

According to Mamoun, the drug combination therapy in their study not only killed the parasites but also induced immunoprotection, meaning that the mice gained protection from future infections.

“If patients are treated with this combination therapy, you might have cleared the infection and also mounted immunity to subsequent infections,” Mamoun said.

Vydyam noted that their findings are particularly significant because they tested the drug combination in vitro, meaning outside living organisms, and in vivo, or in living organisms. Unlike malaria parasites, which don’t currently have mouse models to test drug efficacy, babesiosis parasites were able to be cultured in vivo in immunocompromised and immunocompetent mice.

“Babesia duncani is the only parasite that can culture in vitro continuously in red blood cells,” Vydyam said. “Once we determined their effectiveness, we tested them in animal models to test their efficacy.”

Peter J. Krause, a senior research scientist in epidemiology, previously collaborated with Mamoun on analyzing babesiosis’ genetic mechanisms. For Krause, Vydyam and Mamoun’s findings are critical because babesiosis can be transmitted via blood transfusions. He hopes that new combination therapy can reduce infection rates in vulnerable patient populations.

“Most people do well with current accommodations,” Krause said. “But people who are immunocompromised, which includes people with HIV and cancer, usually have a more severe acute illness, and many can go up to months or even years of therapy, and there is still a 20 percent mortality rate in the group.”

To ensure their drug combination can combat new babesiosis strains, Vydyam and Mamoun plan to conduct additional clinical trials to examine the efficacy of the combination therapy in human subjects. Vydyam said they hope to study whether the combination therapy provides protection for more strains beyond Babesiosis duncani.

Babesiosis is the second most commonly reported tick-borne disease in Connecticut.