Yale professors disagree with federal and state COVID-19 vaccine distribution plans

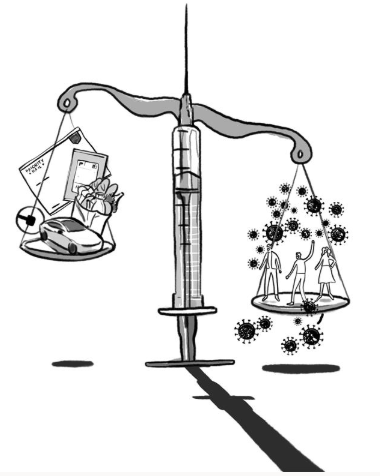

Yale professors Shan Soe-Lin and Robert Hecht disagree with current federal and state plans for COVID-19 vaccine allocation. They argue that to “accelerate the sclerotic pace of the rollout,” COVID-19 hot spots should be targeted with the vaccine first, rather than prioritizing front-line workers like Uber drivers and grocery store workers.

Dora Guo, Illustrations Editor

With information about the COVID-19 vaccine flooding the national discourse, two Yale professors penned an op-ed for the New York Times last month outlining their recommendations for the most effective vaccine distribution practices, which conflict with the current federal and state strategies.

The state of Connecticut is currently in Phase 1b of its vaccine rollout. After immunizing health care personnel, long-term care facility residents and medical first responders, individuals 75 and older are now eligible for the vaccine. People between ages 65 and 74 are set to get vaccinated during a later stage of Phase 1b, beginning in mid-February, followed by front-line essential workers including farmworkers, grocery store staff and U.S. Postal Service employees and residents and staff of some select congregate living conditions.

However, professor of clinical epidemiology at the Yale School of Public Health Robert Hecht and professor Shan Soe-Lin, a lecturer at the Yale Jackson Institute for Global Affairs, published an op-ed in the New York Times on Jan. 10, critiquing the government’s plan to vaccinate front-line workers instead of prioritizing COVID-19 hot spots — areas where case numbers are currently the highest.

“We disagree with the federal and state panels that are trying to select people for [Phase 1b] based on occupation,” Soe-Lin and Hecht wrote in the article. “Targeting hot spots will bring down new infections fastest for all of us, saving jobs and lives.”

Additionally, Hecht and Soe-Lin described that the hot spot approach will help to eliminate existing bureaucratic hurdles, as patients would merely need to show proof of residence using documentation such as a driver’s license or a utility bill, rather than undergoing convoluted screenings to verify occupation and receive the vaccine.

“Prioritizing locations with the highest incidence with the vaccine would maximize reductions in transmission, and then eventually case counts, hospitalizations and deaths,” Soe-Lin wrote in an email to the News. “Cutting transmission quickly is essential to reopening the economy more rapidly, as well as reducing the chances for the virus to continue to mutate and escape the vaccine.”

To implement the hot spot strategy, the authors suggest that public health officials should refer to statewide data and prioritize communities for vaccination where the most coronavirus cases per capita have emerged in the past two weeks.

Hecht and Soe-Lin note that ideally, within seven days of distributing the vaccines to the biggest hot spots, nearly 60 to 70 percent of the population in these infection epicenters will be immunized against coronavirus, helping to achieve herd immunity. However, problems with data collection present obstacles to this approach.

“[One] deficiency is the lack of timely data at all levels reporting on the efficiency of vaccinations that would allow public health professionals to rapidly redistribute vaccines from where there are excess to those that need more,” Soe-Lin wrote in an email to the News.

Claudia Debruyn SPH ’21, one of the former executive directors of the HAVEN Free Clinic — which provides primary care free of charge to many uninsured adults in New Haven — expressed concerns about how a hot spot approach could affect the vaccine rollout to marginalized communities.

She explained that many patients have already confronted large barriers in access to COVID-19 testing and care. Among these challenges are language and transportation barriers, as much of the information on COVID-19 is disseminated only in English, and testing facilities are not always located in the communities they are intended to serve. As a result, reliable data about regions where the incidence of new COVID-19 cases is the highest, which could inform where the vaccines are distributed under the hot spot approach, might be inaccurate.

“Utilizing a ‘hot spot’ approach has the potential to actually worsen equitable vaccine rollout,” Debruyn wrote in an email to the News. “Since this approach relies on ‘solid data on the numbers of new infections’, vulnerable communities’ risk will be underrepresented and therefore not sufficiently prioritized.”

Soe-Lin also mentioned that although the Biden administration has at the least composed a basic plan for vaccine rollout and that Connecticut’s distribution is more efficient than many states, it is still challenging to predict and plan for vaccine shipments, as they vary weekly.

Soe-Lin noted that federal and state governments have done little to transition the vaccine rollout plan to an initiative that specifically targets the largest COVID-19 hot spots.

“Unfortunately, nothing has been done to my knowledge to implement a hot spot-focused strategy,” Soe-Lin wrote to the News. “Across almost all jurisdictions, there is a strong and repeated pattern where most of the vaccine coverage is occurring in populations and neighborhoods that are least at-risk.”

Albert Ko — department chair of epidemiology — said that regardless of the strategy adopted in the latter part of Phase 1b, implementation of any given strategy will be a challenge for the United States.

Ko explained that the nation has no experience in executing mass vaccination campaigns and is a country in which extraordinary amounts of funding was poured into vaccine development, with relatively little money allocated toward distribution plans.

“I think targeting [hot spots] is okay, but it is still going to be complicated,” Ko said.

The CDC reports that 608,600 COVID-19 vaccine doses have been distributed to Connecticut, and 465,008 doses have been administered in the state, as of Feb. 3.

Sydney Gray | sydney.gray@yale.edu