Nonprofit seeks to build new non-congregate shelter

Columbus House, an organization that provides shelter services to unhoused people in Connecticut, applied to the New Haven Board of Zoning Appeals for approval to build a new non-congregate housing facility.

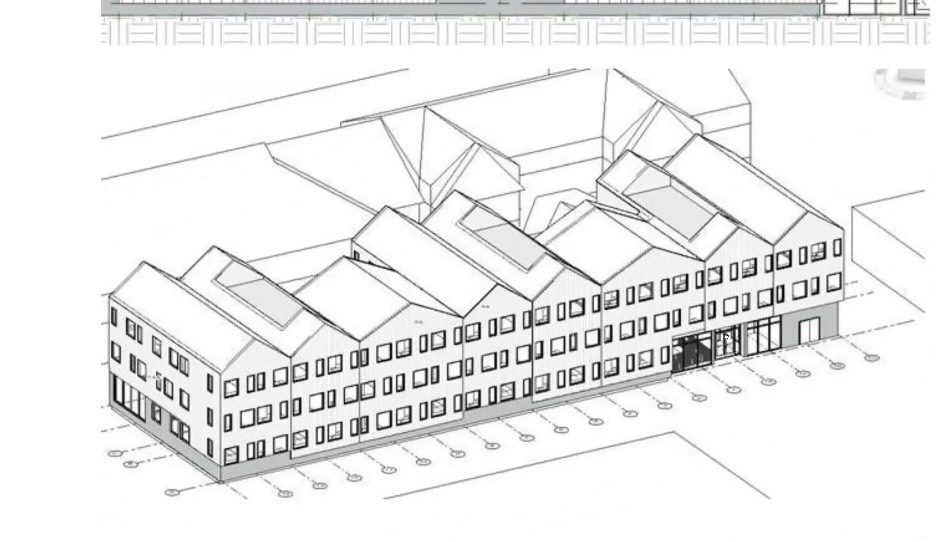

Courtesy of Ben Trachton

Columbus House, a housing and emergency shelter service in New Haven, appealed to the city for an exception to zoning codes on Tuesday night in the hopes of constructing a non-congregate shelter at 592 Ella T. Grasso Blvd.

Rather than house individuals in open spaces, non-congregate shelters provide people with separate rooms for more privacy. Columbus House’s current location at 586 Ella T. Grasso Blvd. has a waiting list of over 150 people, according to Kelly Fitzgerald, the vice president of economic mobility at United Way of Greater New Haven.

The new construction seeks to expand housing capacity and provide unhoused individuals with more resources. However, 592 Ella T. Grasso Blvd is located in a “light industry zone” which does not allow for residential use. In order to gain approval for the building, Columbus House representatives applied for a zoning use variance, which — if approved — will grant the organization an exception to zoning codes and enable the group to commence the new construction. Representatives advocated in favor of the organization’s appeals and discussed the benefits of non-congregate shelters at Tuesday’s meeting.

“What Columbus House is proposing really helps provide a safe, dignified place for people to stay while they’re trying to stabilize their housing,” said Fitzgerald. “Ultimately, our goal … is to really meet the different types of needs of people who are experiencing homelessness and provide different types of sheltering.”

According to Karen Scott, the project engineer for Columbus House, the new building will include 79 sleeping rooms, each with an attached bathroom. Of these sleeping rooms, 49 will be meant for single-occupancy use, and 30 will be used as accessible units or as double-occupancy rooms meant to house two people. Additionally, first-floor bedroom units will be raised above the sidewalk by about five feet to enhance privacy.

Hill Alder Evelyn Rodriguez said that the shelter’s non-congregate model is particularly important because it provides more flexibility to opposite-gender couples who wish to live together, as congregate shelters typically separate people based on gender.

Rodriguez also claimed the shelter would be more attractive to unhoused individuals who may choose to temporarily reside in local parks or abandoned houses, which poses a threat to their health and safety.

“They will have a better place of dignity and compassion, with increased privacy, a place where they can keep their belongings safely, and where they can have private conversations to address their personal lives with staff in the facility,” she said.

Fitzgerald described non-congregate shelters as an “attested model.” During the pandemic, Fitzgerald said that many organizations utilized hotels to provide shelter for unhoused people in order to prevent the spread of COVID-19.

The change, according to Fitzgerald, led to a “significant difference” in the engagement of people who were experiencing homelessness.

“People were more willing to come inside,” she said. “That helps us meet our ultimate goal of moving people into housing.”

Fitzgerald explained that providing people with a sense of autonomy and independence allows Columbus House to engage in helping people find long-term solutions through talking to case managers.

Margaret Middleton, the CEO of Columbus House, noted that the hotel model — an example of the non-congregate shelter model — also helped support unhoused individuals with mental disabilities such as autism.

“For these individuals, the sensory overload of brushing your teeth, eating, sleeping in a large room with dozens of strangers, prevents them from wanting to access our services at all,” Middleton said. “The redesigned shelter holds the promise of a better space, equipped to contain the spread of infectious disease, ensuring that we’re prepared for future pandemics.”

Middleton said that the new construction would help Columbus House be better equipped to provide residential services to an aging population by creating new accessible units.

Ben Trachton, a housing attorney who appealed on behalf of Columbus House at Tuesday’s meeting, admitted that the potential construction requires a “level of deviation” from the zoning ordinance. However, he said he believes that the zoning ordinance is outdated.

“Its most recent revision did not take into account the general trends in housing the homeless,” Trachton said.

Such trends, he mentioned, involve a transition away from congregate-style shelters, and instead toward non-congregate shelters which afford individuals more privacy.

Laura Brown, executive director of the City Plan Department, acknowledged that land use within the city has changed since the city’s zoning codes were created. Although zoning codes have been continually updated in past years, Brown said, the most recent full update of zoning codes was in 1965.

“It’s been a lot of years since then, and industrial processes and the types of chemicals used and the types of manufacturing that is predominant in our economy has changed quite a bit,” Brown said. “Our needs related to housing have changed a lot in that time. People are looking for different things.”

Brown, who also led Tuesday’s BZA meeting, explained that although zoning variances allow for exceptions to the zoning ordinance, changing land use over time indicates a need to reform the current zoning ordinance in order to better fit the needs of the city.

According to Karen DuBois-Walton, head of the New Haven Housing Authority, the BZA generally takes community testimony into consideration while making their decisions.

Tuesday’s meeting took place at 6:30 p.m. over Zoom.