Harvard vows to pull investments from fossil fuel industry, leaving Yale behind

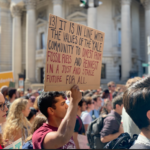

The move comes after years of student pressure at both Yale and Harvard to fully divest their endowments.

Creative Commons

Harvard University — Yale’s fiercest rival — announced on Thursday that it would end all investments in the fossil fuel industry. The decision leaves Yale with a dwindling number of peers who have kept investments in the industry.

Harvard President Lawrence Bacow said that the university has ended its direct investments in companies that explore for or develop fossil fuels and that its indirect investments through private equity funds — which account for less than 2 percent of the endowment — in the industry will soon lapse without renewal. He committed to keeping Harvard’s $41 billion endowment out of the industry for reasons of financial prudence, though he did not use the language of “divestment.”

The change comes after years of student activism which often placed the university in headlines for its refusal to divest from the industry. At the 2019 Harvard-Yale football game, students, faculty and alumni from both universities rushed the field to protest their institution’s entanglements with the industry. Last spring, Yale announced more stringent standards for investment. Despite those rules, it has not joined its peers — notably Columbia, Brown and now Harvard — in a blanket divestment from the industry.

“When people started working on this campaign at Yale years and years ago, they would say that Yale has an opportunity to be a leader on this issue,” said Moses Goren ’23, a member of the Endowment Justice Coalition. “That clearly is no longer the case. Yale is definitely playing catch up.”

The new investment principles that Yale adopted last spring include investing in companies that provide accurate information about climate science and avoiding exploration and production of fossil fuels that generate high levels of greenhouse gas emissions relative to energy supplied — namely coal.

Since then, the Advisory Committee on Investor Responsibility, which develops recommendations for socially responsible investing, has published a list of 45 companies that Yale will not invest in online.

Jonathan Macey LAW ’82, Chair of the ACIR, argued that this “name and shame” approach has distinct advantages over Harvard’s blanket divestment decision. If responsible investors leave the space, it minimizes the incentives for fossil fuel companies to act responsibly, Macey said. Yale’s approach isolates and focuses attention on the worst actors, he added.

“The bottom line on this is that everybody knows that, unfortunately, fossil fuels are going to be a feature of the economy for the immediate future,” Macey said. “The question is: how should a responsible endowment live with that reality? The Yale position essentially, in my view, is to recognize the reality and try to deal in the most effective way possible with the world as we know it. I think that approach is qualitatively superior to the approach Harvard is taking, which is just to pretend that the problem doesn’t exist.”

But Josephine Steuer Ingall ’24, a member of the Endowment Justice Coalition, questioned whether there was data to back up Yale’s assertion that worse actors would fill the gaps in the market. In developing its new principles for investment in the fossil fuel industry, the University cited the current make up of the fossil fuel industry and noted there was an “apparent danger” that production could fall to state-controlled oil companies without investor oversight.

But Steuer Ingall added that it was “ridiculous” to expect an industry to self police and that assessing fossil fuel companies predominantly on their greenhouse gas emissions ignored other types of harm they have perpetrated, which include violations of Indigenous land, as well as air and water pollution.

“There is no such thing, in my opinion, as best practices for eradicating the habitability of the planet,” Steuer Ingall said. “If we’re going to allow such standards, we’re going to divide up the industry into ‘okay fueling of climate destruction’ and ‘not okay fueling of climate destruction.’”

Macey noted that there is a “very compelling” argument for blanket divestment from the fossil fuel industry, but he maintained that Yale’s approach was superior given society’s current reliance on fossil fuels.

“We really need to transition away from reliance on fossil fuels as a society, globally,” Macey said. “If we do that, then fossil fuels will be a really bad investment. If the planet is going to survive, fossil fuels have to become a bad investment.”

Harvard’s decision was hailed as a victory for student activists. Macey said that student action by the EJC and Fossil Fuel Divest Harvard has had a “great deal of influence” on the two universities.

Isha Sangani, a member of Fossil Fuel Divest Harvard, said that she hopes Harvard’s influence means that the change will reverberate throughout higher education. Because Harvard is the world’s richest university and one of the most prestigious, she hopes its decision will spur other institutions to reconsider their investments, she said.

She added that the language of Bacow’s announcement, particularly his claim that fossil fuel investments are no longer “prudent,” echoes the legal complaint that the group filed with the Massachusetts Attorney General’s Office.

“If anybody [at Yale] was feeling discouraged, you should take this news as encouragement and a testament to the fact that student activism does work,” Sangani said. “We won, basically, against the world’s richest university. So just keep fighting and things will turn the right way.”

Recently, the EJC has urged students to withhold their student activities fee and any donations to Yale in opposition to the University’s ties to the fossil fuel industry and “austerity” in New Haven.

The ACIR is also focusing on questions of divestment from the private prison industry, Puerto Rican debt and Sudan.