Yale law professor represents Ukraine at World Court

Harold Hongju Koh, Sterling Professor of international law at Yale Law School, argued on behalf of Ukraine against Russian invasion alongside a team of lawyers at the International Court of Justice.

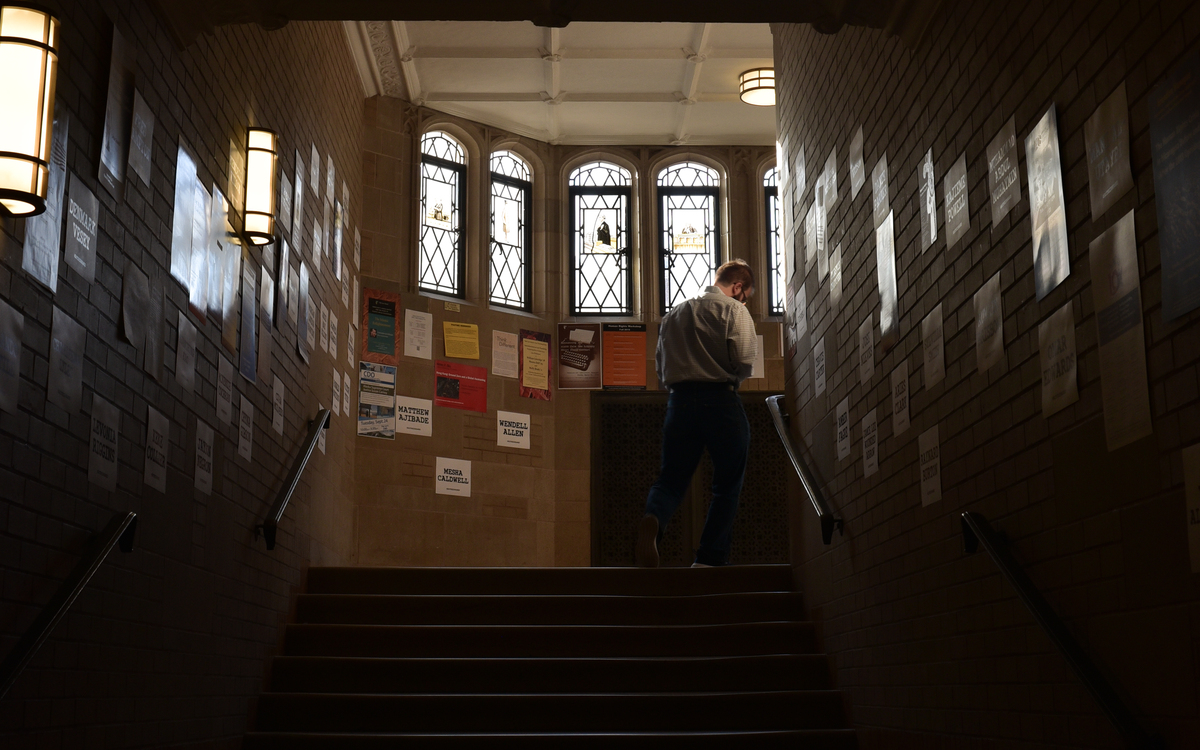

Ryan Chiao, Senior Photographer

Last week, a team of international lawyers including former Dean of Yale Law School Harold Hongju Koh represented Ukraine at the International Court of Justice, or ICJ, in the Hague.

Koh is a Sterling Professor of international law at Yale Law School and has also served as Legal Adviser for the United States Department of State under Barack Obama. In an interview with the News, Koh refuted Vladimir Putin’s claim — that he had sent troops to Ukraine on a special military operation to prevent genocide from being committed by Neo Nazis.

Koh explained that there are two types of lies being made by the Russians: factual lies and legal lies. The factual lie, he said, is that Ukraine was committing genocide in the Donetsk and Luhansk regions. The legal lie is that the Russians were obligated to prevent this genocide, and that Russia had the legal right to invade Ukraine as a preemptive measure.

“The whole world knows that that’s a lie,” Koh said.

Lea Brilmayer, Howard M. Holtzmann professor of international law at Yale Law School, explained that the International Court of Justice — which was set up by the United Nations in 1945 — requires consent to jurisdiction by both states involved in a case in order to resolve disputes.

Koh noted that the Russian claims gave the International Court of Justice jurisdiction. If Russia had not created the dispute, Koh argued, there would not be a case for the court to pursue.

“[The International Court of Justice is] very valuable in that it helps to clarify international law,” Brilmayer said.

Both Russia and Ukraine have ratified the 1948 Genocide Convention, which allows parties to bring disputes against each other involving interpretation, application or fulfillment of the genocide treaty to the World Court.

Russia did not appear at the court hearing, and sent a letter to the court saying it “ha[d] decided not to participate in the oral proceedings due to open on 7 March 2022.”

“If [Russia] thought they actually had a lawful basis to do this, they would appear and defend,” Koh said.

While Koh and the rest of Ukraine’s legal team are waiting for a court order to get the United Nations’ peacekeeping forces involved, they requested and received provisional measure orders very quickly. Koh added that the ICJ judges understood the urgency of the situation.

A March 7 press release outlined the measures requested by Ukraine.

“The Russian Federation shall immediately suspend the military operations commenced on 24 February 2022 that have as their stated purpose and objective the prevention and punishment of a claimed genocide in the Luhansk and Donetsk oblasts of Ukraine,” the press release stated. “The Russian Federation shall immediately ensure that any military or irregular armed units which may be directed or supported by it, as well as any organizations and persons which may be subject to its control, direction or influence, take no steps in furtherance of the military operations which have as their stated purpose and objective preventing or punishing Ukraine for committing genocide.”

Ukraine also requested that Russia refrain from any actions that may “aggravate or extend the dispute.”

Koh continued that, while Putin’s short game is centered around force, the world’s long game is law. Over the past two weeks, he said, the case has developed into much more than a dispute between Russia and Ukraine — rather, it has become a fight between Russia and “the post-World War II international legal order.”

“It’s a really genuine question,” Koh said. “If a permanent 5 member of the UN can just engage in a war of aggression and atrocity against an innocent neighbor and get away with it, then … why do we have a UN charter? Why do we have an International Court of Justice?”

To understand the necessity of the law, Koh recalled a previous visit he had made to Kyiv in March 2020, where he was invited to judge an international law moot court competition due to his previous role in arguing for Ukraine at the ICJ for a separate case.

When Koh arrived, a young law student took him on a tour around the city, and he recalled that she expressed great pride in Kyiv. Just two years later, he saw her on CNN in full military gear working at a military hospital, where she testified that she was surrounded by dead bodies and asked viewers what happened to the laws she once studied.

“Our lawsuit was designed to be part of the answer [to her question],” Koh said. “It’s here … your friends are here, we’re fighting for you with law.”

Both Koh and Brilmayer reflected on Yale’s role in international law, both in the past and in the future. Koh said that students come to Yale to “level the playing field” and use their knowledge to create a more just, equal and fair world — not to accept the status quo and “let bullies push other people around.”

“Yale should be very proud to have [Koh] there [at the ICJ],” Brilmayer said. “This is obviously a very important matter. It’s a real sign of his esteem in [the] profession.”

Koh has taught at Yale Law School since 1985.