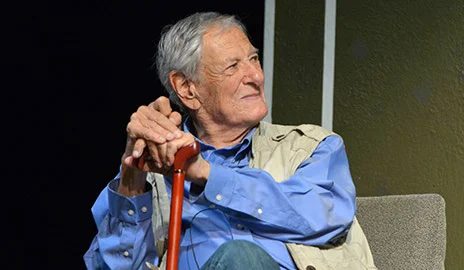

Remembering Yale Repertory Theatre founder Robert Brustein

Brustein was a prominent theater-maker and theater critic, writing for The New Republic and The Huffington Post, as well as publishing 16 books on theater and society.

Yale News

Passionate theater critic and advocate for non-profit theater Robert “Bob” Brustein died at the age of 96 on Oct. 29 in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Brustein became Dean of the Yale School of Drama — now the David Geffen School of Drama — in 1966 after leaving his professorship at Columbia University. After arriving in New Haven, he founded the Yale Repertory Theatre. He remained at Yale for 13 years before departing for Harvard, where he established the American Repertory Theatre in 1979.

“Bob … refin[ed] the conservatory model of training at Yale by professionalizing the faculty and bringing distinguished guest artists to New Haven,” wrote James Bundy DRA ’95, the current Drama School dean and artistic director of the Yale Repertory Theatre. “He was committed to exploring new directions in playwriting and theater making and also to relevant and vivid productions of canonical works. These remain hallmarks of the Rep.”

Student demand brought Brustein to Yale, said Lonnie Carter DRA ’69, who was a first-year student at the beginning of Brustein’s tenure. While Carter had not yet been a student, he characterized students’ desire to bring Brustein from Columbia as a “mutiny.”

Before Brustein became the dean of the Drama School in 1966, David Epstein DRA ’68, a student when Brustein arrived, was considering leaving the school. Epstein said that it focused on “asinine” practices that did not reflect the “excitement of what was happening in the theater in the 60s.”

This all changed with Brustein, who brought in renowned actors from across the U.S. and from England to teach –– such as Kenneth Haig, Irene Worth and Richard Gillman. According to Epstein, Brustein focused on bringing in active professionals who could better prepare drama students for the world of professional theater.

In addition to this new approach to pedagogy, Brustein embraced newness and experimentation in the productions held at the Yale Repertory Theatre. After his graduation, Epstein said that Brustein “kept him around,” putting on Epstein’s plays at the Theater and asking Epstein to be the first producer of the newly-formed Yale Cabaret.

“You were given the opportunity to try anything,” said Epstein. “That’s a pretty terrific passport to be given. Two of my closest, longest-lasting, writing friends from Yale — Lonnie Carter ‘69 and Robert Bob Montgomery ’71 — are terrific playwrights, but their style of writing was totally different from mine. Bob was a big supporter of both of those guys as well. He was not looking for what had been done before. He was looking for what was coming next.”

Brustein’s legacy in the world of theater has been matched by very few American theater-makers, said Ron Daniels, a director and frequent collaborator at the Yale Repertory Theatre. To those who were close to Brustein, his legacy also encompassed his sense of “adventure” as a theater-maker and “deep” loyalty to the actors and directors he worked with, Daniels said.

The artistic liberties Brustein gave to the actors and directors of the Yale Repertory Theatre reflected how much he cared about the work, Daniels told the News.

“He gave me enormous freedom,” Daniels said. “He was always after new ideas, after new thinking, after new people to work with, and at the same time, deeply, deeply loyal. That was the most important thing about him — he really cared about the work, and he cared about the ideas in the work.”

Brustein shied away from productions that “everybody else was doing,” per Daniels. Brustein was “adamantly” against showcasing the works of popular playwrights at the time, such as Tennessee Williams and Arthur Miller, both of whom had frequently showcased their work on Broadway productions and were established names in the world of theater.

Beyond his list of accomplishments, Brustein is remembered as a “family man,” who not only cared about his wife and children but also about members of the theater community, whom he considered a part of his family.

For instance, Brustein’s loyalty and care for Daniels extended beyond their shared time at the Yale Rep — Brustein offered Daniels a job after coincidentally running into him in London.

“My prospect of being out of work was looming ahead,” said Daniels. “I just happened to bump into Bob on the street in Sloane Square in England. I told him, ‘Look, I’m going to be out of work.’ And he said, ‘Come to me immediately.’ Not a moment’s hesitation. And that’s what I mean by loyalty. He was true to his word.”

Brustein was committed to the idea of a theater company — an organization made up of actors, directors and producers that collectively run a production. Brustein “held people together,” said Daniels, who, among other theater-makers and actors, followed Brustein to Harvard after his departure from Yale.

During Brustein’s time at Harvard, Daniels said that Brustein’s theater philosophy and “aesthetic aspirations” largely remained the same. Founding members and professors at the Drama School and Yale Repertory Theatre, such as Rob Orchard DRA ’72, Jeremy Geidt and Jan Geidt, played similar roles at the American Repertory Theatre.

“I’m not sure that that happens nowadays,” said Daniels. “Nowadays, it’s much more to do with ad hoc. You employ actors, they do the play, and then they go away. They don’t stay for 234 plays.”

Brustein was also an outspoken advocate for non-profit theater. In an article with the New York Times, he said that the profit-driven goals of commercial theater did not align with those of noncommercial theater, which aimed to “create the conditions whereby works of art can be known.”

While the Yale Repertory Theatre was not profit-focused, Daniels and Carter said that they never felt restricted by financial constraints during their times as directors and actors, respectively. Carter said that he never felt that he “didn’t know where [his] next check was coming from.”

According to Daniels, the Yale Repertory Theatre was not concerned about finances because of Brustein’s strong fundraising efforts. He was a natural charmer and could easily get wealthy patrons “to open their purses,” said Daniels. Carter also said that the Yale Repertory Theatre enjoyed financial support from the University, largely due to former Yale President Kingman Brewster’s support of the arts.

“[The University] was keeping the lights on,” said Carter. “The president at the time supported Bob and said ‘this is nonprofit theater, and we’re doing an alternative to commercial theater. We’re gonna do what’s challenging to us and challenging to our audiences.’”

This financial luxury and stability was unique for a nonprofit theater at that time, said Carter, and it’s still unique today. He recalled how Arvin Brown, a former artistic director of Long Wharf Theatre, held out his cup and said ‘please give me money.’”

Theater companies still confront these “economic realities” today, said Daniels. He said that these financial difficulties were exacerbated by the pandemic and pointed to the large number of companies closing down or experiencing cutbacks in funding.

As challenging as it is to sustain nonprofit theater, Bundy said that profit-driven theater fails to provide a space to pose “urgent moral and aesthetic questions” raised by great works of dramatic literature.

“Robert Brustein saw clearly that Yale could invest in artistry and challenging ideas for the benefit of audiences and of the field,” wrote Bundy. “In the 57 years since he founded Yale Rep, the work done at our theater, and by graduates in the field, has proven the value of his thesis over and over again, and the wider resident nonprofit theater movement that owes so much to his vision has become the predominant engine of artistry in both the nonprofit and for-profit theater.”

During his tenure as artistic director of the Yale Repertory Theatre, from 1966 to 1979, and of the American Repertory Theatre, from 1980 to 2002, Brustein oversaw over 200 productions.