Anabel Moore

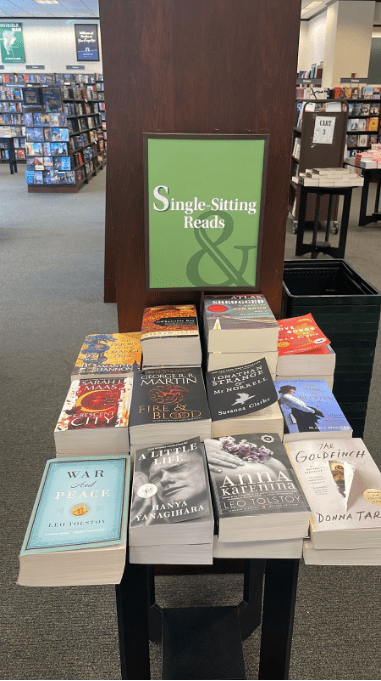

At a Barnes & Noble off the A1A in Stuart, Florida, I picked out two books. The first was for pleasure, Donna Tartt’s “A Secret History,” an accompaniment to “The Goldfinch,” which I devoured over the course of four days the summer between high school and college. The second I chose at the encouragement of my father, who insisted that I’d be through “A Secret History” in less than a week and needed to decide on another read in celebration of my twentieth birthday. It wasn’t tradition to pick out books on my birthday, but it certainly felt as though it should’ve been. As someone who self-admittedly loves to buy books I’ll never read, it simply felt right that I should be in a chain bookstore with my dad on my birthday over spring break, skimming the fiction section and wondering how on Earth Barnes and Noble employees could argue that “War and Peace” and “A Little Life” are “Single Sitting Reads.”

I spent a lot of time alone as a kid; it’s cliché to say that this is why I love reading, but reading was the pastime that staved off loneliness. My brothers are decades older than me; I was closer and more comfortable with my parents’ friends than kids my own age. My after-school activities all throughout elementary school were remarkably straightforward: watch “Rachel Ray: 30-Minute-Meals” — the best programming on my parents’ hand-me-down 30-channel box television, take free throws in the driveway, or read. Today, I am a terrible cook, a sub-50 percent free throw shooter and a student who spends more time looking at the haphazard stacks of books beneath my common room window than actually reading them.

I wish I could read for enjoyment more at Yale. I read my bookmarks more than the books themselves; my biology assignments make excellent placeholders. I used to try to read for fifteen minutes before bed every night, either an opinion piece from The New York Times or J.M. Coetzee’s “Elizabeth Costello.” I chose to be busy instead, and write a lot, too. I find it bizarre that I write for fun more than I read for fun; perhaps that’s why I spend an embarrassing amount of time on Thesaurus.com.

It was in the context of this longing that I chose Joan Didion’s “The Year of Magical Thinking.” I had watched “The Center Will Not Hold” while jogging on the treadmill. I felt guilty that my first and only exposure to Didion was accompanied by violent huffing and puffing, particularly as she visibly withered away in the film.

It was the only work by Dideon that Barnes & Noble had in stock. On my twentieth birthday, I wanted honesty and an accurate description of a worst-case scenario. In my free time, I wanted both the amusement of Tartt’s academic novel and the integrity of Dideon’s prose. As I read about art history and cell signaling and twentieth-century smallpox eradication for my courses, topics that all start to feel a bit hand-wavey the more time you spend with them, I wanted to read something that was raw and decidedly real. I’m not the first person to say this, but “The Year of Magical Thinking” reminds us that we all die.

I was a year older, still closer to the beginning of my life than the end, but spending my time staring at Kaplan-Meier curves and reading about childhood tuberculosis in low-income countries and trying like hell to understand what the seventeenth-century Dutch were trying to do with vanitas art. My courses this semester are preoccupied with death: evading it, eradicating it, respecting it and understanding it.

But if I’m being truthful, I picked up “The Year of Magical Thinking” because I wanted to know what would happen and what I might feel when I eventually lose someone I love. I do not presume to live a perfectly privileged life; I know this day will come.

A few days ago, I came across an old Yale Daily News article, published just after Commencement for the class of 2012. Written by Marina Keegan, it’s titled “The Opposite of Loneliness,” and was featured in a special Commencement issue of the News. A few days after graduation, Marina died in a car accident. She was driving with her boyfriend to Cape Cod, a job at the New Yorker awaiting her after summer’s end. Her prose is made even more ephemeral by her fate, but I couldn’t shake a line: “We’re so young. We can’t, we MUST not lose this sense of possibility because in the end, it’s all we have.” She tells the class of 2012 to “make something happen to this world.” She tells them, too, that they can change their minds. They can start over. They can do whatever they want.

Somewhere between Rachel Ray and Marvin Chun’s first-year address, I forgot about this freedom. I didn’t want to explore “what-ifs” anymore. I didn’t want to imagine, or speculate, or dream a dream that didn’t align with what I had been thinking for the last ten years. I wanted to do what had to be done, to put in the work, reap the rewards, and continue on my way. I wanted to be prepared; I conflated the word “possibility” with “risk.”

There is a possibility things could go wrong. There is a possibility that my hard work will not pay off. There is a possibility that my family will get COVID-19 and die. There is a possibility that bad things will happen. There is a possibility that I will make the wrong decision, and all of this scares me more than I can begin to articulate.

Yet none of this has materialized. Joan Didion is right; “grief turns out to be a place none of us know until we reach it.” My preparation is pointless. When I chose “The Year of Magical Thinking,” I told my dad that I wanted to appreciate Didion’s writing – I, too, wanted to be able to write a sentence so beautiful it hurt. But in reality, I picked it up because in the year 2023 I was turning twenty and he was turning seventy and all of a sudden his age was something I was meant to be concerned with. I felt in my bones the possibility of big, scary feelings lurking around a blind corner.

Though I wish I could read for enjoyment at Yale, I realize that I never really read for enjoyment in the first place. I’m always looking for answers, and sometimes answers to questions I don’t need to be asking. I don’t need to know what will happen if I lose someone. It will happen, and I will be okay. I am too young to waste this promise of possibility to fear, to lose this time in the pursuit of answers, only to let these answers gather dust on the ledge beneath the window.

Books always filled a void, but if I’m being honest, that void no longer exists at this school. Like Keegan, I’m in the web of this “elusive, indefinable, opposite of loneliness.” Like Keegan, I have no idea what is around the next bend. All I know is that each birthday, I will pick out a book. I might read it, I might not — who knows. I am “in love, impressed, humbled and scared.” The answers to my questions are out there somewhere. And for now, that knowledge is enough.