Students present research detailing Yale’s history with slavery

At a Beinecke event on Monday, Miguel Ceballo-Countryman, Patrick Hayes and Mackenzie Hawkins each shared research they conducted as part of their fall “Slavery, Race and Yale” seminar.

Yale News

On Monday, three students from the “Slavery, Race and Yale” fall seminar shared historical findings about the University’s ties to slavery.

The students spoke virtually at a Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library event entitled “Yale & Slavery Research — Student Perspectives.” Taught by Professors Edward Rugemer and Crystal Feimster with teaching fellow Teanu Reid, the “Slavery, Race and Yale” seminar developed from the Yale and Slavery Research Project and its mission to explore and detail Yale’s history with racial slavery from its inception in 1701 through the late-19th century. Miguel Ceballo-Countryman ’23, Patrick Hayes ’24 and Mackenzie Hawkins ’22 each discussed different aspects of Yale’s history and connection with slavery.

“I was interested in sharing my research because I want anyone who is willing to listen, as well as those who aren’t, to learn about the university’s history with slavery, how that history continues to this day, and how we might create a university that is truly abolitionist, supporting of those it has oppressed, and changing its entrenched, racist practices,” Hayes said in an email to the News.

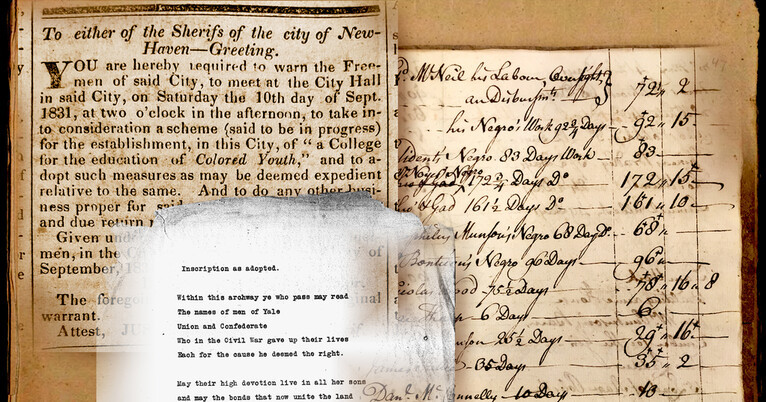

Ceballo-Countryman discussed the 1831 proposal to build a Black college in New Haven. He noted that many Black leaders spent years working to conceive of this future college.

The proposal, however, was voted down by property-owning white voters 700 to four, many of whom had connections with the University. No Yale professors voted to endorse the college. Following the vote, many members of the white community went through Black neighborhoods and threatened violence, which Ceballo-Countryman said was an intimidation tactic.

“It is important that we view this failed proposal for a Black college not as a missed opportunity but rather as a historical moment in which the racial barriers to an exclusivity of higher education was cemented — a historical moment that would have lasting implications throughout the country,” Ceballo-Countryman said at the event.

Hayes conducted a biography of James Philemon Holcombe, a student who attended Yale from 1838-40 yet did not graduate. Holcombe grew up in Virginia, and while his family previously owned enslaved people, they freed them during Holcombe’s childhood and paid for some of them to move to Liberia. However, once Holcombe left Yale, he became an ardent secessionist and supporter of slavery. Beyond teaching law at the University of Virginia, Holcombe was a passionate debater and made a series of speeches supporting his racist views.

In the presentation, Hayes explored how Holcombe’s education at Yale altered his perception of the morality of slavery. Hayes suggests that Yale’s cultural and academic environment allowed Holcombe to change his views on slavery without much pushback from the University.

“The argument that I am making in my paper is that it is really the institutions that shape us,” Hayes said at the event.

Hawkins gave an analysis of Yale’s Civil War Memorial, which today is a part of the Schwarzman Center. While other institutions erected memorials just a few years after the Civil War, Yale did not build its own until 1915.

Hawkins offered an account of the internal politics and debates within the committee that voted on the physical structure and design of the memorial. Composed of white men — some of whom supported the Union and some the Confederacy — the committee eventually agreed to the phrase “Each for the cause he deemed the right” to describe the different sides Yale students fought on. The words “Union” and “Confederate” were cut from initial designs, and slavery was never mentioned in the inscription. According to Hawkins, the University actively chose not to reference slavery and its own history with slavery.

“The University had an opportunity to at least hint at the causes, at least hint that there were divisions,” Hawkins said in her presentation. “But the explicit purpose of this memorial, both nationally and at Yale, was to emphasize that everybody was in this together, which is a blatant historical inaccuracy.”

Following discussions of their work, the three students answered questions posed by audience members and the moderator Michael Morand, communications director for the Beinecke.

“Complicity is a choice,” Hayes said. “Taking the middle ground is a choice. It is also a choice every year since these events occurred that the University has decided not to change.”

During the conversation, the students also applied the history they learned in the seminar to tackle social issues pertaining to the University, particularly its relationship with the New Haven and Black communities. In closing, students were asked how the University ought to remember and grapple with its past.

Ceballo-Countryman urged the University to incorporate and listen to the voices of New Haven residents who are affected by its actions and political stances. Similarly, Hawkins and Hayes said that the University needs to increase its funding towards New Haven and fight against the inequalities that it perpetuates through its actions.

“I think that there’s a lot to be said of the inequalities that the University perpetuates today,” Hawkins, who formerly served as editor in chief of the News, said at the event. “Its lack of contribution to New Haven, even though that is increasing; its lack of support for New Haven public schools relative to the University’s endowment and the list could go on and on — our legacies of the exact same historical through-line that started at the University’s founding in 1701 and that appeared at these touch points that we each focus on in our presentations.”

Hawkins also emphasized the importance of the seminar and the Yale and Slavery Working Group in continuing to unconver Yale’s relationships with slavery.

“I don’t think that it will be nearly enough to produce a manuscript or a book or a conference or something at the end of this [seminar] and then wash our hands of that and say, ‘Okay, we did it, we remembered,’” Hawkins said. “If we’re still doing the exact same things then what did we learn by remembering?”

This was the first of two Beinecke events detailing students’ research in the “Slavery, Race and Yale” seminar. The second event will occur on March 7.

Correction, Feb. 4: This article previously stated that Ezra Stiles was the only Yale professor who voted in favor of the Black college. This is an historical inaccuracy. Ezra Stiles Ely was a Yale alumnus and Philadelphia pastor who wrote in favor of the Black college yet did not participate in the voting process.