YSPH research reveals relocation and re-education of Ukrainian children

A report published by the Humanitarian Research Lab at YSPH documents a widespread Russian initiative to displace Ukrainian children to education and adoption facilities.

Courtesy of Yale Humanitarian Research Lab

A new report from the Yale School of Public Health has uncovered a systematic Russian program to re-educate and relocate Ukrainian children, which researchers allege is a violation of international law.

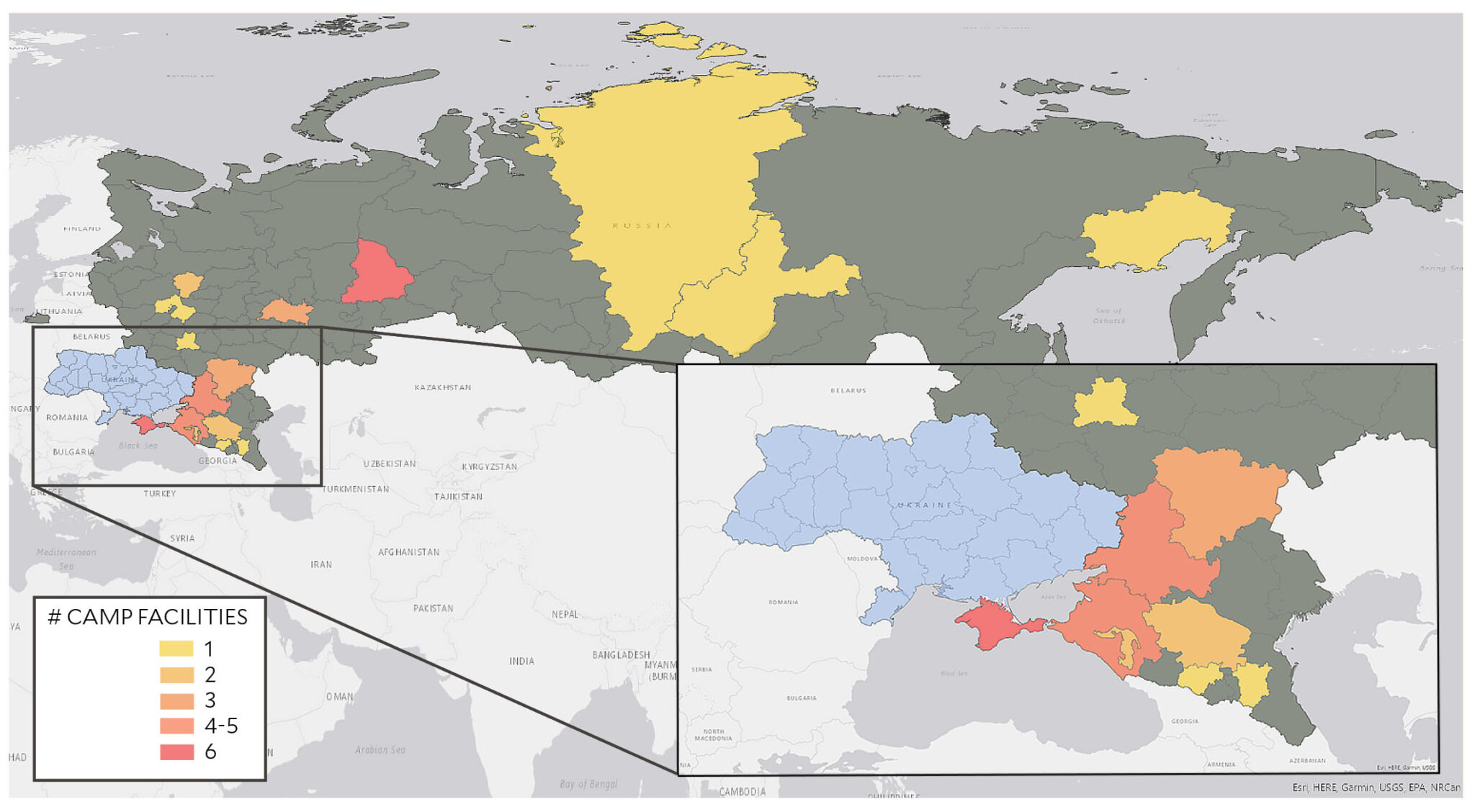

The report — published on Feb. 14 by YSPH’s Humanitarian Research Lab as part of the State Department-funded Conflict Observatory program — documented the relocation of over 6,000 children from Ukraine via a network of 43 re-education and adoption facilities stretching from Crimea to Siberia.

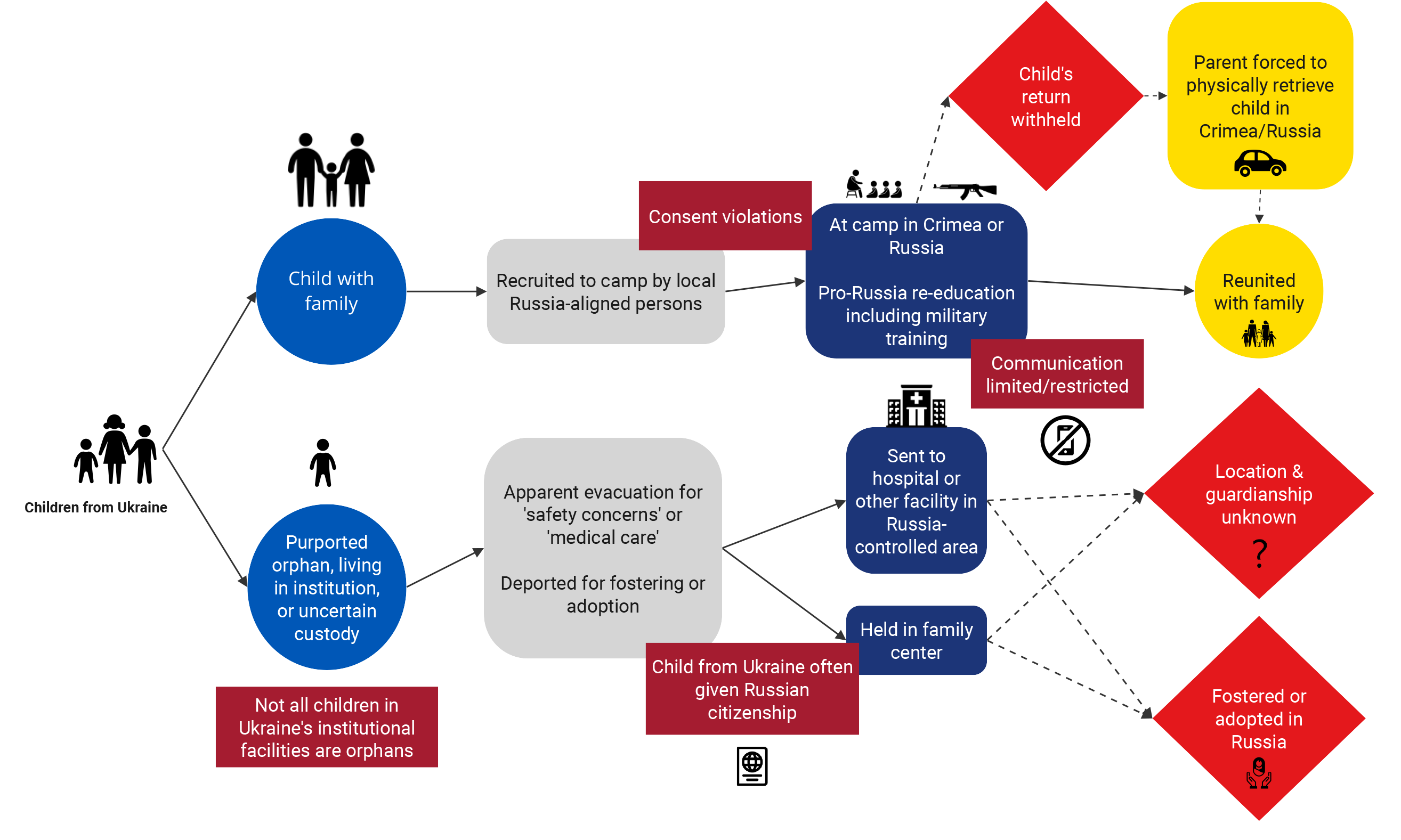

According to the report, the majority of camps engage in pro-Russia re-education initiatives, while others have given children military training and prevented their return to their parents — violating international human rights law.

“We were able to clearly identify immediately that the activities that Russia’s officials were describing were violations of the Fourth Geneva Convention,” said Nathaniel Raymond, executive director of the HRL. “In some cases, there were also alleged crimes against humanity in violation of the 1998 Rome Statute, on prohibitions of transfer of children from one group to another for the purposes of erasing national identity.”

According to Raymond, the research team had been “watching” the relocation program since early Spring 2022 — shortly after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine — and was a “clear priority” for the U.S. government. By October or November, the HRL researchers had developed the methodology and data sources to begin documenting the transfer of Ukrainian children.

To do so, Raymond noted that HRL used open-source information to develop their understanding of the network of relocations, camps, re-education efforts and adoption and foster placements. HRL identified facilities through social media posts, government announcements and news reports. They also obtained public telegram messages from Russian officials and from Ukrainian parents who shared potential information about the children’s whereabouts.

The research team then verified these locations using high resolution satellite imagery of suspected camp locations, according to Raymond. A combination of the satellite imagery, reference photographs and videos on camp websites, along with user-generated photos on mapping sites like Yandex Maps, were employed to geolocate camp facilities. Each location was independently confirmed by at least two researchers before being included in the report.

To accomplish the task of large open-source research, the HRL worked with a research group across the University. Although, according to Raymond, the names of team members and group sizes could not be disclosed for security reasons, he emphasized that individuals from multiple parts of the University were involved.

“Yale students should know there are heroes among [them],” Raymond said. “You may not know who they are, but when you see this work, you should be proud of it. Because it’s your colleagues and fellow Yalies who are making it happen.”

The HRL was able to conduct open-source research because, rather than concealing the relocation networks’ existence, the Russian officials involved celebrated it. According to the report, the camps were marketed as either recreational or humanitarian: to provide kids with vacations or to save them from active warzones.

As a result, many officials “celebrate” their involvement in social media posts, interviews to media outlets or photographs with Ukrainian children at Russian-controlled facilities.

“They really believe that somehow Ukraine should not exist, that Russia has the right to rule the territory that is Ukraine and that the people in that territory should be Russian,” said David Simon, director of the Genocide Studies Program who was not involved in the study. “The reason why I think that they’re so unabashed in saying what they’re doing is that … they don’t believe in Ukraine.”

The report’s findings, however, paint an even more grim picture.

Since the Russian invasion of Ukraine on Feb. 24, 2022, more than 6,000 Ukrainian children have been held in Russia’s custody across at least 43 facilities, including a psychiatric hospital and a family center. The network stretches from Russian-occupied Crimea to Siberia: a camp in Magadan — 3900 miles away from Ukraine’s border — is closer to the United States than Ukraine.

The true number of children and camps, Raymond added, is likely “significantly higher.”

According to the report, 78 percent of camps were engaged in “systematic re-education efforts” that exposed Ukrainian children to pro-Russia academic, cultural and in some instances, military-style training. Multiple camps are advertised as “integration programs” to assimilate Ukrainian children into the Russian government’s “vision of national culture, history, and society.”

At least two camps hosted orphaned children and placed them with Russian foster families. More than 20 of those Ukrainian children were placed with families in Moscow and enrolled in local schools.

According to the report, the network is centrally operated by Russia’s federal government, including local, regional, and federal leaders at every level of government. At least 12 of the individuals involved in the program are not currently on United States or international sanctions lists.

“It’s tragic to say this, but on virtually every front, whatever the official Russian press release is, the one thing you can count on is that the opposite is true,” said Jeffrey Sonnenfeld, SOM assistant dean. His research team has investigated the exodus of companies from Russia after its invasion of Ukraine.

In many instances, the report continued, consent from Ukrainian childrens’ parents were obtained under duress. The report details how parents were made to sign over power of attorney, how agreed-upon terms of stay lengths were violated and parents’ refusal to allow their children to attend camps “were ignored” by organizers.

In at least four camps — including Medvezhonok which hosts at least 300 Ukrainian youth — childrens’ returns to their parents were suspended, and they are being held past their scheduled date of return. Parents also report being unable to obtain information about their children’s whereabouts after their return is delayed.

“It’s worse than misinformation: it’s disinformation,” Sonnenfeld said. “It’s intentional deceit, and that’s what we have here. And this is just one more piece of evidence to say that [Putin is] … targeting civilian populations.”

According to Raymond, the systematic relocation, re-education and resettlement of Ukrainian children is “absolutely” a prima facie violation of human rights and the laws of war.

He underscored that point, especially, since he believes that the “number of locations and children is significantly higher”— a theory he intends to prove.

The report emphasized that the program’s adoption, unnecessary transfer, political indoctrination, military training and prolonged custody without parental consent of Ukrainian minors may constitute potential violations of the Convention on the Rights of the Child and the Geneva Conventions.

Simon also pointed out Article 2(e) of the United Nations Convention on the Prevention of the Crime of Genocide, which includes “forcibly transferring children” of one group to another as one of the crimes that constitute genocide.

“Russia even changed its adoption laws to make it easier to adopt Ukrainian kids and transfer those Ukrainian kids to Russia, so that they may be raised as Russian kids,” Simon told the News. “That’s what forcibly transferring children of a group to another group means. There are only five sets of acts that qualify under that convention, and it’s one of them.”

For some Ukranian students at Yale, the report was startling.

According to Sofiya Bidochko ’24, a Ukrainian-American student whose extended family lives in Ukraine, the report’s documentation of Russian mass-relocation and re-education initiatives makes her “sick to [her] stomach”

“I grew up learning about my great great grandfather being forcibly sent to his death to a labor camp in Siberia and I questioned how such an act was ever allowed to be permitted by the world,” Bidochko wrote to the News. “And now I learn of these poor children who are also sent to ‘reeducation’ camps … all of them being forced into an identity meant to erase them of being Ukrainian, and I cannot comprehend how this is not being stopped before our eyes.”

Moving forward, Raymond and the HRL hope to continue investigating humanitarian crises in Ukraine. While Raymond mentioned an additional investigation on another Ukraine-related crisis slated to be published next month, he emphasized how the report has had a “catalytic effect.”

On Wednesday, Feb. 22, Raymond and Kaveh Khoshnood, the faculty director of the HRL, will present their findings at a United Nations summit addressing atrocities committed by Russia in Ukraine.

While Khoshnood understands that the report might not immediately cause a change in policy, he remains optimistic about the research that his team conducts.

“We do however know that such evidence-based reports do not always “translate” into appropriate policy and practice changes,” Khoshnood wrote to the News. “This is a challenge that public health academicians typically experience on many topics, but regardless of this challenge, we will do our best.”

Since the report’s release, it has been cited by Vice President Kamala Harris and Secretary of State Anthony Blinken in calls to investigate atrocities committed in Ukraine.

A State Department press release on the report declared the relocation network a “grave breach of the Fourth Geneva Convention” and called for Russia to “immediately halt” transfers and deportation, to return children to their families, to provide registration lists of the children and to grant access to outside independent observers to the network’s facilities.

The Conflict Observatory was announced by the State Department on May 17, 2022.