Cecilia Lee

The Legend of Barefoot Kid crosses state lines two weeks into the school year, when my friend Lila calls to tell me about the insane time she’s having at college in Minnesota. She spends the better part of an hour discussing people I’ve never met and parties I didn’t attend while I hide in my dorm room from the nine strangers I apparently live with now, until she stops, mid-anecdote: “Wait,” she says, “have I told you about Tor yet?”

***

Tor Olsson is a first year at Macalester College who doesn’t wear shoes — hence, “Barefoot Kid.” Two months into the semester, he is already a campus idol. Most of the freshmen — Tor’s classmates, hookups, enemies and friends, tablemates at his future alumni events — are somewhat devoted to him. He features in their TikToks and stars in their drunk group chat messages. They ask him to sign pieces of paper with his feet; They steal a pair of rainbow Puma slides from his dorm; They start and spread rumors that he got kicked out of the Whole Foods on Selby Avenue — no shoes, no service. Spotting Tor, even if he’s just sitting in Café Mac eating ketchup straight out of the packet, is a celebrity encounter. just ran into him in the science building, Lila texts me, 😍 barefoot king. He is a central part of life at Macalester, as fixed and as focal as the Twin Cities: Minneapolis on the left, St. Paul on the right and Tor in the middle, talking to everyone, his feet callused and filthy and bare.

***

I’ve spent a grand total of 41 minutes on a FaceTime call staring at Tor, and I can report with confidence that for an enigma, he looks normal. If you took a child actor, some best friend on the Disney Channel, and stretched him out into a college freshman — over six feet tall, rail-thin, and sporting a haircut the internet lovingly deems “the white boy swoosh”— you would end up with a guy who looked like Tor. (I write “wholesome (?)” in my notes.)

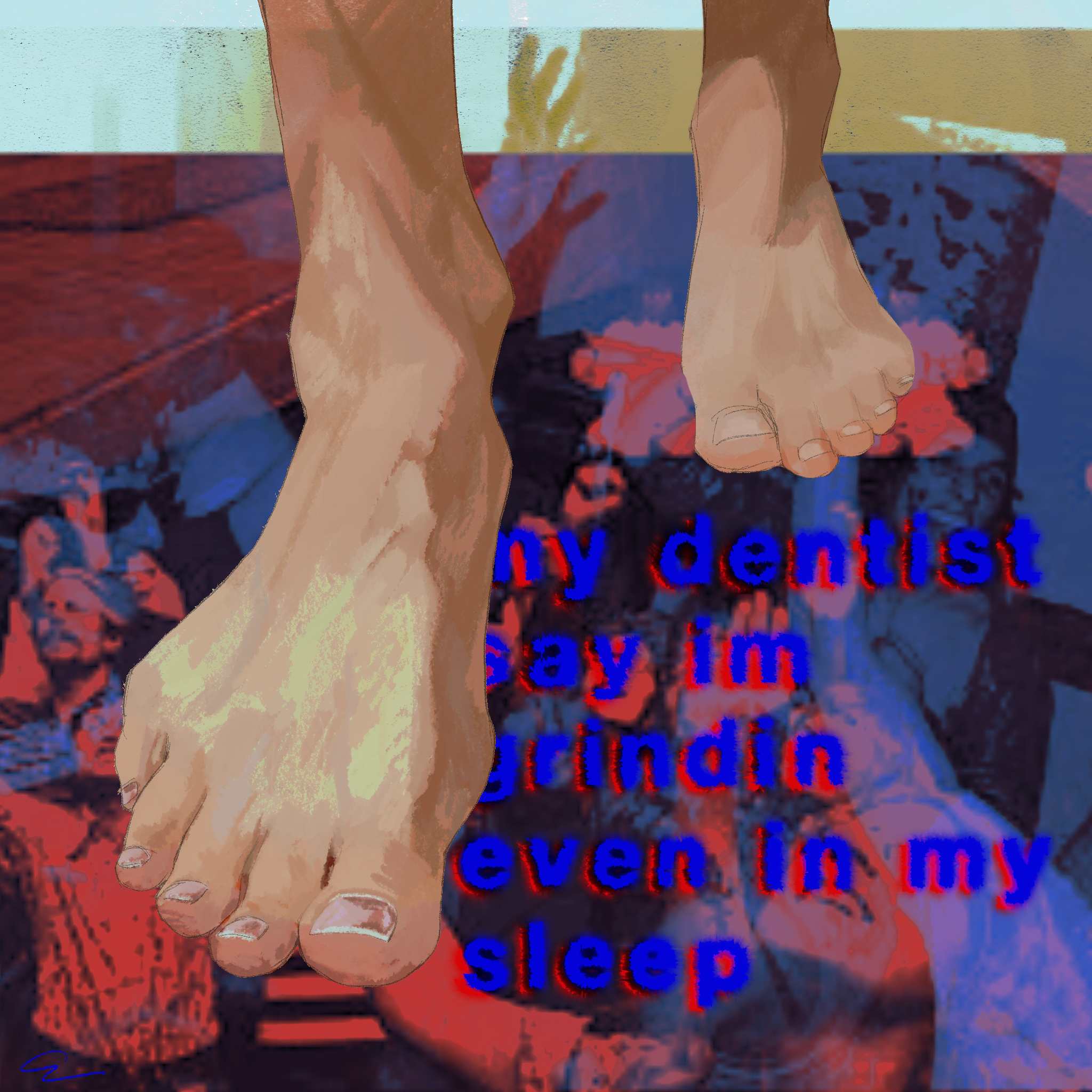

Tor is half an hour late to our interview. He’s late to most everything, I learn. There is a lot that’s more important to Tor than being on time: his religious studies class, the cross country and track teams, a global perspective on climate change, the six-foot long tapestry of a (fake) DaBaby tweet (“my dentist say im grindin even in my sleep”) hanging in his dorm room and the fact that I know that he knows that DaBaby was cancelled. We talk about bagpipes and astronauts and his recent meditations on spirituality, until finally I ask Tor how he thinks his classmates perceive him. He says, “So you’ve heard that around campus I’m sort of known as like the guy who walks around without shoes, right?” I have. “Which I totally didn’t plan for, actually,” he stresses. In fact, he’s sort of confused why no one else is going shoeless. “It feels so good. I don’t like my feet to be trapped. When I showed up at college there was so much grass — it’s like, why not?”

Tor is a firm believer in the barefoot lifestyle. Nonetheless, he does not proselytize — he doesn’t need to; We come to him. (“I should try it,” I say, very excited. “Don’t feel pressured to,” he replies.) He’s aware of the inevitability of snow — Minnesota winters are already hard enough for those wearing boots. “We’ll see when we get there,” he says. He’s either using the royal we or referring to the potential legion of unsolicited barefoot followers over whom he could reign. “We’ll get there later. We’ll hang in there until it’s too much to handle.”

***

In the middle of our interview Tor mentions that he is — get this — a representative for the Class of 2025 on the Macalester College Student Government, and I make the professional journalistic choice to not say Wait, what? out loud. Lila confesses that his candidacy caught her off guard too: “Mostly because when somebody has, like, a gimmick, I assume that’s their way of getting their name out there.” Tor already had a Thing — did he really need another?

He can certainly multitask. People voted for him, of course — he’s a nice dude — and he speaks passionately — if vaguely — about how he wants to bridge the gap between the powerful administration and the student body and reach out to the first-year class. But scandal rocked the election cycle. Another candidate ran on the policy of mandatory shoes in Café Mac, targeting not Tor Olsson, good-guy political organizer, but Barefoot Kid, unhygienic communal diner. There were five seats available for Representative; When Tor won, his opponent did too.

***

How does it feel, barely two months into your first semester, to be inspiring negative ad campaigns, to be known for just one thing? Tor says he’s collected reputations like this his entire life. “Up until probably fourth and fifth grade, I was, like, always the super quiet kid; I just did not talk. I was sort of known for that. People just really had no idea what I was thinking,” he says. But they needed to find out. “Who is this kid? What’s he up to? For some reason, people find something to kind of, like, idolize me for. I sort of wish it didn’t happen as much.” Tor’s been thinking about it a lot, lately, and he can’t figure out what it is about himself — why this happens to him everywhere he goes.

I think this is a little ridiculous. It is almost impossible to be innocent in the creation of your own cult of personality, one so flourishing that random students from other colleges write charmed essays about you. Maybe Tor doesn’t actively seek the spotlight, but I do think it has become the place where he feels most comfortable. It’s easy to imagine getting used to that attention, that individuality, that influence. Why wouldn’t he cling to a parodic version of his own behavior, especially in the first difficult months of freshman year?

After all, Tor is like his friends, his classmates and his interviewer: somewhere people don’t really know him, trying to figure out how to let them know him. He’s never done this alone before; He has a twin sister, and he didn’t realize how hard it would be to go to college without her. “We’re very similar,” Tor says. It’s unclear if she also hates shoes. “We know each other like we know ourselves, sort of, which is really crazy.” Being a twin can be defining. For better or for worse, you’re permanently associated with another person: one half of a whole, part of a package deal. When your twin is at Vassar, 1,200 miles away, who are you?

***

Tor finds comfort in how no one is feeling settled. He could let go a little of the self-consciousness, the social anxiety, when he remembered that everyone was feeling the same — more comfortable with the scheduled academic periods than the nebulous free time for socializing, all worried about how they were presenting themselves to each other.

Many first-years might try to give a polished, collected, blandly nice first impression; For his, Tor emailed his future cross country teammates about how he couldn’t do a cartwheel and was planning on bringing bright pink leopard-print sheets for his dorm bed. He thinks the transition into college helped him to stop overthinking his interactions with others: “The fact that no one’s really comfortable, no one has a lot of people to talk to … that helped me let go of a little bit of the social anxiety.”

I can’t say the same, and I don’t know any other freshmen who can either. After a year and a half spent alone, college is an overcorrection: whether we’re learning, sleeping, eating or using communal bathrooms, we’re constantly with other people. It’s exciting to be face to face again, but it feels like we have to relearn it from scratch: “Be present in conversation, make facial gestures like you’re listening — these things that you haven’t thought about in a while, putting it all back together piece by piece … that’s been overwhelming,” Lila admits.

The pandemic still isn’t over, and it likely never really will be. Everyone could be sent home the moment positive testing rates climb too high. What’s the point of getting invested in these relationships, this place, the person you’re becoming in this new phase of your life? How do you go cold turkey from a year of online everything — when you didn’t have to pretend that you were okay, that you were someone functioning well enough to put shoes on every day — to an entirely new environment, away from home, that constantly demands from you the social and academic fluency you lost in March of 2020?

***

Tor Olsson has made a pretty enviable name for himself; he is, by all accounts, a charming, entrancing conversationalist, a thoughtful, spontaneous friend and a genuine stand-up guy. In the grand tradition of weird extroverts, he wouldn’t make a bad cult leader. He’d find fame rewarding, Tor tells me, if he could be some sort of spiritual leader, inspiring people to separate themselves from their societal constraints. Once, when studying with his teammate Nick, Tor said out of nowhere, “Yesterday, I sat in the fitness center and closed my eyes and tried to levitate for ten minutes.”

Nick: Do you mean meditate?

Tor: No. Levitate. Like, float.

Nick: What are you—how could you do that, Tor?

Tor: Well, I don’t know, but it felt like my soul was leaving my body, so something was happening.

Nick laughs recounting the story. He thought it was ridiculous — but he was sort of convinced. “I’m like, ‘Okay, now I have to try that. Now I have to sit for ten minutes and try to levitate.’ He’ll just say stuff like that. And I love it. Cause now, now I have to think about …” Nick trails off. “What if one day he gets it, you know? What if one day he just floats off the ground? Cause if anyone could do it, he could.”

***

I decide to become Tor’s first long-distance disciple: I spend two hours one evening walking barefoot around my own campus. I get attention, which I love, and cold, which I do not. I think I would recommend it. It is, as promised, freeing. It’s also anxiety-producing, and odd, and fun, and scary, and on top of all of that it kind of hurts — it feels, in other words, the way navigating the new is supposed to feel.