Liam Brogley

I spent countless hours this summer exploring the area around my home. My friends and I would wander, talk, listen to music and take pictures together. It was a simple and rewarding way to keep busy and entertained throughout the summer. It also provided a new way for me to observe my home, Pottstown, Pennsylvania. The little suburban world I grew up in, surrounded by the dead and discarded remnants of American industry, had always seemed so painfully mundane to me. Home felt like a place from which to escape — there had to be bigger cities and more intellectual vitality elsewhere. But, as summer crawled by and I continued to work and take pictures, I came to thoroughly appreciate the authenticity, the almost vulgar honesty, that life at home brought me.

About halfway through this past summer, I bought a 35mm manual SLR camera for $30 at a yardsale. In well over my head, with little prior knowledge of photography, I had to learn the process behind film photography in order to make use of my new camera. Equipped with a phone camera for the better half of my life, I was used to the spray-and-pray method of photography – take as many pictures as you need until you get it right and delete all the rest. Shooting film manually, however, forced me to slow down, take one or two well composed shots of a given subject, and move on.

A typical roll of 35mm film has either 24 or 36 exposures on it. With each exposure (i.e. photo that I want to take) I have to manually adjust the shutter speed and aperture settings on my camera based on readings from a light meter, as well as focus the image. Each shot requires its own series of considerations based on lighting, composition and the type of film I’m shooting on. Once I’ve used every exposure on a given roll of film, I have to get it developed and scanned, a process that can take up to two or three weeks. This delayed gratification to see how an image turns out has made me particularly concerned with the quality of my photos — every detail has to be correct to justify everything that goes into taking and seeing a single photo.

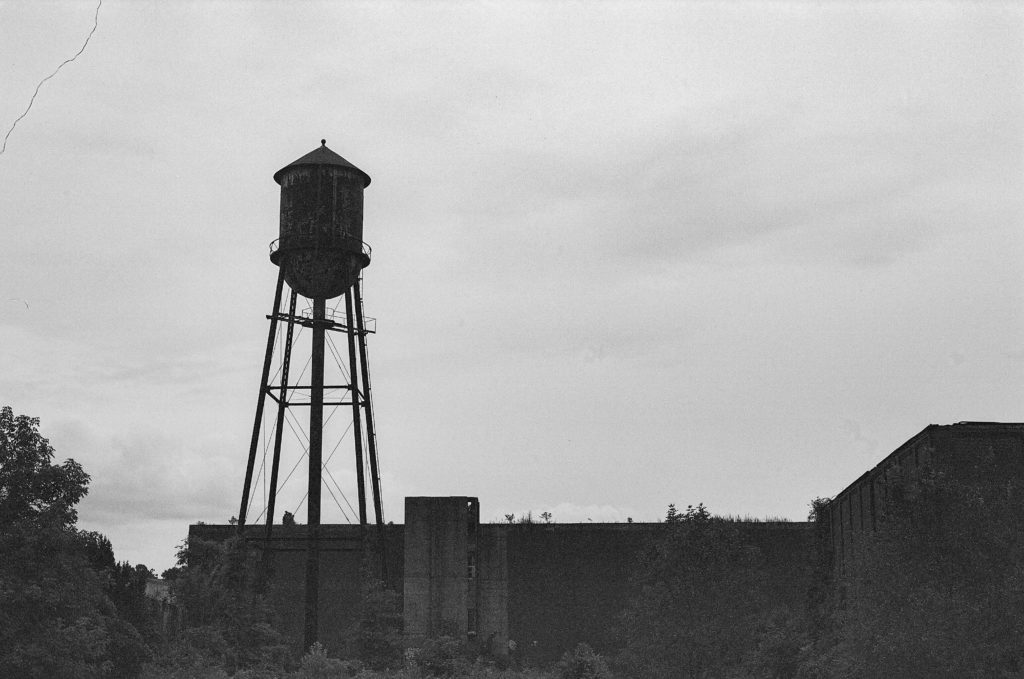

In an effort to elevate the quality of my photography, I began to intensify the attention I gave to my hometown and allowed myself to see beauty where I had before felt disdain. I became singularly concerned with capturing the essence of home through my photos — the pace of life, the charm of its people, its rich industrial history now replaced by economic stagnation and our proximity to nature. Rather than taking photos of everyone and everything in a documentary style, I narrowed down my subject matter, focusing primarily on architectural studies of abandoned industry and street photography.

My architectural studies gave me the opportunity to explore with my friends and to feel wonder at something I was once embarrassed of. No town proudly admits that it is a shell of what it once was, struggling to provide for its residents as job prospects grow farther and farther away from home. For the longest time it felt easier to look past these steel husks and the harsh realities they contained, shifting my gaze outward towards bigger cities and better opportunities. As I explored these spaces with friends, however, their history began to unfold and fascinate us — the fact that sprawling industrial complexes where countless people spent much of their lives working could become abandoned within a generation, and then drowned in overgrowth and graffiti soon after, gave us a resounding sense of temporality. With my camera in hand, I felt that I could draw art, but also anthropological insight, from these places, capturing their state following abandonment, focusing primarily on the ways in which nature attempts to reclaim itself from industry as well as the ways in which individuals leave their marks on these spaces. In the act of photography, I captured these spaces in a particular moment in time, where the nuances of these miniature histories formed the basis of what I found to be so beautiful about them.

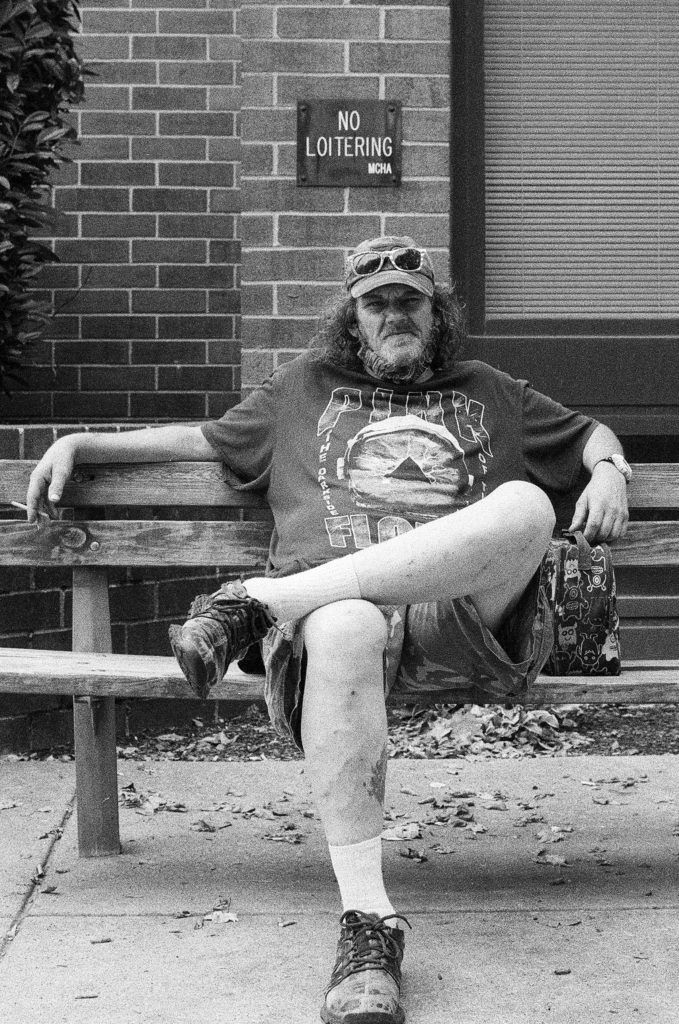

I also took a particular interest in street photography over the summer. Walking the streets of Pottstown with a camera completely recontextualized my view of the town. It gave heart to a place that felt so lifeless; it personalized a place I thought I could just leave behind. The primacy of authenticity over aesthetic purpose necessitated by street photography vitalized my subjects, who were Pottstown residents going about their everyday lives. Through the lens of my camera, I was able to better grasp the appeal of not only my hometown but also its residents, whose lives embody a sense of sincerity which I feel Yale lacks.

At Yale it feels like our language is shrouded in euphemism and mock concern for the events of the world as we ponder this or that from our neo-gothic castles, sleeping comfortably on the promise that we’ll be successful enough that none of these things will affect us. At home, however, I was grounded by my friends, coworkers and family into a real world, a world where detachments permitted by wealth and other forms of privilege that are all too common at Yale simply don’t exist.

I spent the summer working in construction alongside my father, doing manual labor which trivialized so much of my experience at Yale. This university produces a thinking class of individuals, who might only ever be theoretically concerned with what goes into making a building, but after digging the trenches myself, spending days in the beating sun, and looking down at my dirty calloused hands at the end of each day, the intellectual chatter of Yale felt so silly.

I know that part of me wanted to spend my summer at home working construction and taking photos for how distinctly non-Yale it was, with no prospects for academic or professional advancement and certainly no soul-searching abroad in Europe. Perhaps I chose to do so to be able to lord it over those Yale students who could stomach the opulence of the first year dinner, but I’d like to think I did it for a more idealistic reason: before the academic and professional pressures of Yale start to close in, I wanted a final chance to internalize the parts of myself that I won’t allow the university, or anything else, to touch.

With the memories of the place that I am leaving behind, Yale has become a strange new home for me. At the periphery of wealth and power and desperately holding on to the shreds of my idealism, these photos are keepsakes of a place which I hope to keep within me as I pass through life. Contained within them is an embrace of the vulgarity of truth, a dedication to find the beauty of everyday life and a refutation of the cynicism of the bottom dollar. While in themselves they are photos, they contain a world that I took into the palm of my hand and examined gently, finding a place which I am sad to leave behind.