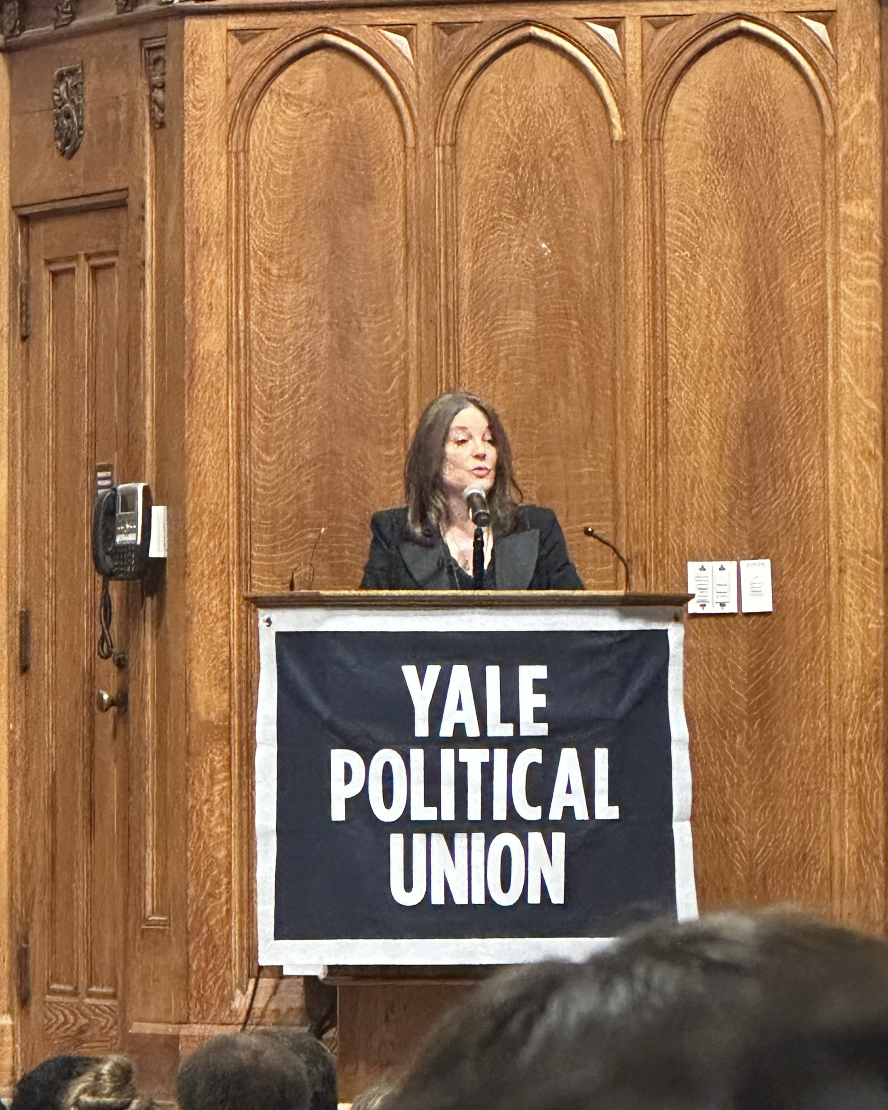

2024 presidential candidate Marianne Williamson talks spirituality and politics at YPU event

Williamson – who has launched a bid for the 2024 presidency – joined the Yale Political Union for a discussion on April 11.

Ines Chomnalez, Contributing Photographer

Marianne Williamson — who recently announced her intention to run as a Democratic candidate in the 2024 presidential election — spoke at Yale about the role that love and spirituality play in progressive politics.

The Yale Political Union hosted the author and spiritual adviser Marianne Williamson for an April 11 discussion titled “A Conversation on Spirituality & Politics.” Williamson, who rose to prominence during her 2020 bid for president, is an advocate for progressive political reforms and has centered her candidacy for office around humanitarian concerns.

“If you think politics has nothing to do with religion, you don’t understand religion,” Williamson said at the event.

The Tuesday evening discussion was attended by approximately 300 students and community members, as well as supporters and volunteers for Williamson’s 2024 campaign. Jean Wang ’24 – president of the YPU and an opinion editor at the News – began the event by clarifying the group’s status as 501(c)(3), meaning that it is a non-partisan and non-profit group that was neither endorsing Williamson’s candidacy nor hosting the event as an opportunity for political fundraising.

Williamson began her address by laying out the fundamentals of her political ideology, before responding to questions from the event’s moderators and attendees. The YPU typically hosts politicians and political thinkers to discuss a resolution in a debate format, but Williamson declined to adhere to this structure.

“I was told that the YPU usually hosts debates,” Williamson said. “But I don’t know how you could debate whether love should rule the world.”

She made clear that her definition of spirituality was not dependent on a particular religious creed, but rather a view of the self as something greater than the physical form of the body.

Williamson dropped out of the 2020 election in Jan. 2020 after her support in the polls dropped to around 1 percent. During the Democratic primary, she was criticized for referring to a vaccine mandate as “Orwellian,” though she later apologized for those comments.

Though her emphasis on love and spirituality has been met with some skepticism within the Democratic party, Williamson was emphatic that historical precedent is on her side. Politics – specifically humanitarian reform – and religion have more often than not been intertwined, she said. She referenced the religious convictions underlying the American Civil Rights movement and the Indian Independence Movement as well as the influence of Quakerism on American suffragettes.

“Progressive politics today being so devoid of this [spiritual] conviction is actually an aberration,” Williamson said.

Williamson took her spiritual conviction one step further by saying that without spirituality, America’s founding ideals were untenable.

Her argument was that the claims of the Declaration of Independence, namely that all men are created equal, evidently stem from an understanding of humans’ spiritual rather than physical equality. Therefore, Williamson argued, to uphold the Declaration of Independence was to uphold that humans are more than flesh and blood.

“That was the first time a nation has ever been founded on the principle of equality of all human beings,” Williamson reflected.

Many of Williamson’s most controversial views surround mental illness and psychiatric interventions. The presidential candidate has routinely expressed skepticism about the efficacy of antidepressants, and has labeled the difference between sadness and clinical depression “artificial.”

During her talk, Williamson expressed chagrin about how often people today – especially women – complain of struggles with anxiety. “Of course you’re anxious,” she told the crowd, insisting that people ought to view their anxiety not as an individual ailment but as a product of dysfunctional society. From there, Williamson encouraged individuals to use their anxiety to motivate political protest and reform.

“I’ve been very disappointed over the last few years, and how many people I’ve heard, particularly women, who just claim to be so traumatized by the state of America today,” Williamson said. “I remind you that the people who walked across the bridge at Selma were traumatized too.”

Tuesday’s discussion was the second time Williamson has visited campus, the first being in 2019 during her first bid for the presidency.

Williamson told the News that she enjoyed visiting college campuses because it allowed her to address a group of people almost exclusively born in the 21st rather than 20th century. This was crucial to Williamson because of her view that each century has its own particular consciousness.

“You’re the first generation of the new millennium,” Williamson said, “So, young people today are carrying with them the burden — a particular burden — of individuation, not just from a previous generation but from a previous way of looking at the world.”

Several attendees of Tuesday’s talk were neither students nor affiliates of the University, but rather supporters of Williamson or active volunteers for her campaign.

In interviews with the News, five of these supporters expressed their admiration for Williamson’s message and her commitment to love and humanitarianism.

“I was very inspired by her tonight,” said Nancy Ladish, who attended the event. “I would think that young people would be very inspired by her too. I thought her message was very hopeful, and the fact that she’s not status quo is what we need today. We need somebody different.”

Three of the Williamson supporters in attendance told the News that they had been following Williamson for over a decade, and became interested in her politics after reading her 2007 book “The Age of Miracles.” They all communicated a willingness to move across state boundaries and follow Williamson throughout the course of her presidential run.

“I’m so proud of her for saying what everyone’s thinking and not saying,” Williamson volunteer Cindy Nye told the News. “She has a very clear idea of where this country came from, how we landed in the mess that we’re in, and what we need to do to get out of it.

The 2024 election will be the 60th quadrennial presidential election.