Jessai Flores

It was the Saturday night before PRIDE in New York. We’d all come down to see our friends — him from Washington D.C., me from Boston, joined by a third friend from Philadelphia.

The club was hotter than we’d hoped. Why had I agreed to pay a $15 cover? 15 dollars? What kind of establishment charges 15 dollars for the service of being bathed in sweat, heat and the miasma of loneliness?

We left soon after, stumbling onto the G train, drunk with exhaustion: him, thinking about how much later than his bedtime it was already, me, intoxicated by the memories of my last summer living in Clinton Hill. I assumed that was the end of the night, both of us too tired to make small talk.

I didn’t want to go home in silence, so I asked him about twinhood. I don’t care much about twinhood. But it got him talking anyway.

We somehow got to the topic of life after college. He brought it up. Adulthood. Senior year. What to make of the last of the best years of your life? He told me he was scared of how easy it is to lose people.

We talked for three hours after that. We got to my friends’ apartment at 3 a.m., caked with sweat and the grime of the post 6 train. I desperately needed to shower. Instead, we sat on the floor of the apartment and turned on the AC.

Exhausted, I blurted out a dormant thought.

“What is my biggest flaw?”

He laughed.

“Do you actually want me to answer that question? I don’t really think you have any —”

“Well then is there anything about me that ever frustrates you?”

“Sometimes you interrupt me when I’m talking.”

I laughed.

“I interrupt you?”

“Yeah. You’re an amazing friend and a very good listener. Actually, I’m not sure why we’re discussing this but sometimes when we’re talking one-on-one you interrupt me, almost like you’re trying to finish my sentences. Which, you know, you are likely to know what I’m about to say most of the time. But sometimes we’re having very emotional conversations and you put thoughts that I’m experiencing in words that are so emotionally charged yet just slightly imprecise and I don’t know how to —

“Bring them back to the abstract level of thought with which they existed in your brain?”

“Exactly.”

“I just did it again.”

How had I never noticed that before? I let him finish the rest of his thought, aware for the first time of the number of instances in which I had to restrain myself from interjecting.

A small part of it was impatience, bred by years of too-long conversation with people who had never been schooled in the wonders of brevity.

Most of it was well-intentioned though. Enthusiasm, empathy — even love. A sign of my complete engagement in conversation. The moment when you finish a friend’s thought and they exclaim, “yes,” validating not only that you have understood their account but exactly what they felt in the moment they are describing.

And some of it was hereditary. My mum does the same thing all the time. She is far more egregious than I am.

How had I never noticed it before? My tiny but ubiquitous social tic. It was so believable. We continued talking for another hour or so, about party buddies and our responsibility to the world, until we were forced to admit that talking any longer would ruin any semblance of Sunday plans.

I went to bed happier than I had been in months.

When people ask me what my love language is, I tend to equivocate. Actually, I tend to lecture the questioner about the modalities of love and the proliferation of self-help buzzwords in the public sphere. The answer is definitely quality time.

It’s one of the things I love most about Yale. Even amidst its demands and the expectations it expects you to have of yourself, amidst its impossibilities of seeing that friend who is taking five classes and running three clubs, it offers four years of quality time with your favorite people — if you seek it out.

I am rarely free for lunches. They are always blocked off on my calendar, reserved for weekly meals with my closest friends. These are the assurance that even at my busiest, I will be abreast of the going-ons in their lives. These meals breathe air into college life, pushing back against the asphyxiating hold of a college schedule.

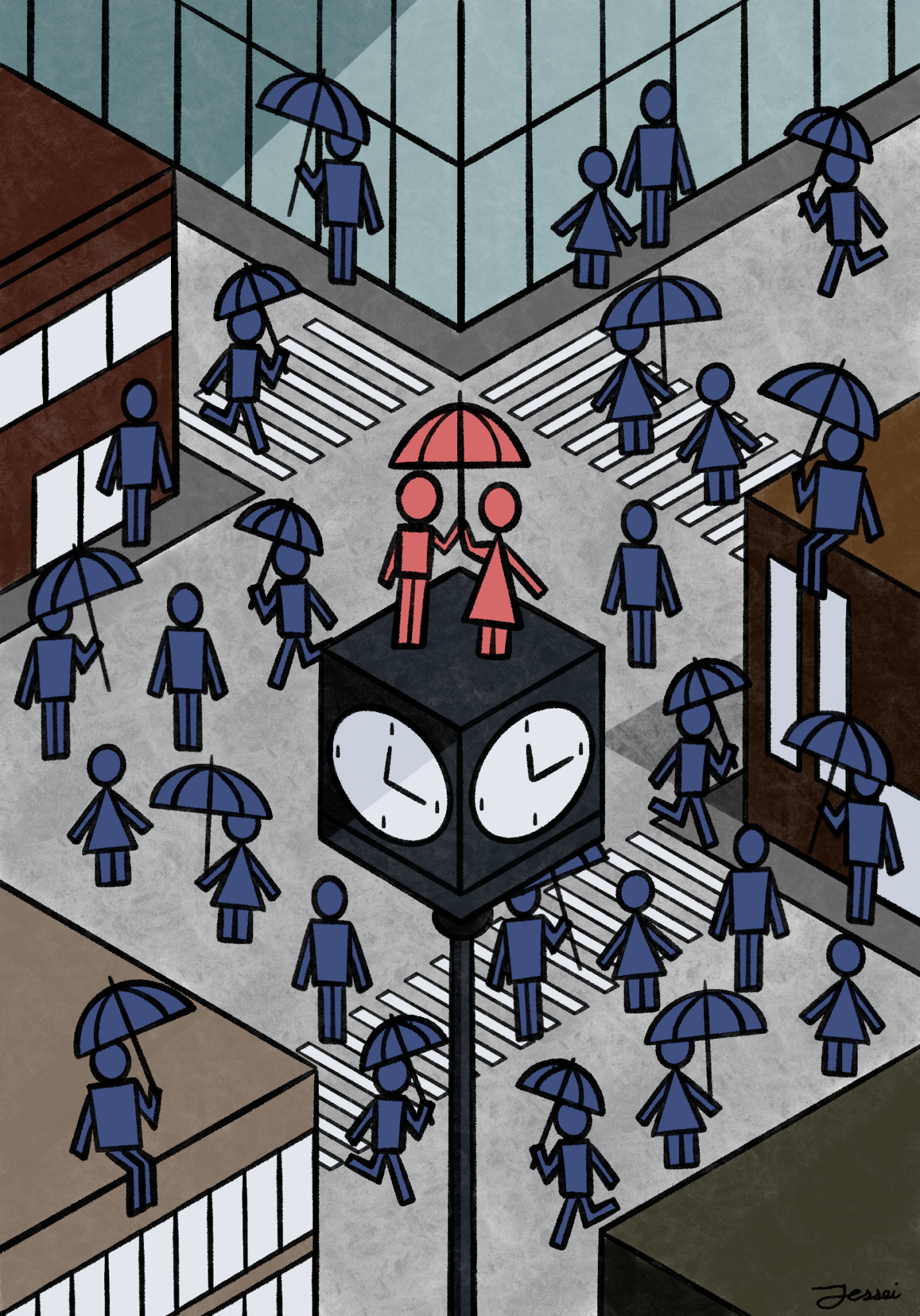

And then sometimes, I meet my friends at the beginning of a Saturday night or we walk down Hillhouse at 10 p.m. or bike to East Rock. These are the special occasions when we carve out chunks of time with an unspecified start and end and gift them to each other. That’s when I realize what we’re missing.

We delude ourselves into thinking that we can schedule profundity, that an hour-long block of time will be enough to feel like part of a life that does not stop when you aren’t thinking about it anymore. It’s the best we can do. You might not hear about the song that reminded them of how scared they were to grow older last Monday, but at least you’ll hear about their break-up.

So many of my best memories at college have been spontaneous. The night after the horror movie. When we talked about evil and capitalism and Hannah Arendt, about criminal justice and corporate responsibility. The night on the rooftop of the AEPi house. Christening a therapy hammock. The day at the bookstore. The night we spent in New York City.

I’m a senior now. It sucks but I’ve known it was coming for three years. And if you’re a first-year reading this, you’ll be here so much quicker than you think is possible.

Every senior I’ve spoken to has said their one piece of advice is to make time for the people you love. I might amend that to say make availability for them.

Of course we are available for the people we love. My friends know that they can wake me up in the middle of the night if they’re hurting.

But what I mean by availability is something more generous. Not just time in the calendared sense. Time for the sake of time. The possibility of possibility. Enough time to allow for late-night conversations unfettered by the fear of a 9 a.m. Saturday wake-up for that fifth club that you just joined because you thought you needed something else on your resume.

Serendipity operates through the channels of time. Make these channels as broad as they can be. I’m torn between the impulse to do everything I can before I see Yale disappear in front of me and the impossibility of knowing what “doing everything” even means. There are so many lasts to experience. There is so much to be done. It is terrifying to imagine — and even more terrifying to admit — that we’ll graduate from this place not having done everything we ever wanted to. That we’ve disappointed ourselves. Of course, we have. It’s our biggest flaw.

On our worst days, human connection feels like a paltry consolation for the tangible trophies of achievement. To love is to lose. Friends move to the Midwest. The ones who don’t move to London. Still, achievements are not the pillars on which you build your castle of memories. They are not the things you ramble to your kids about when you are old.

There is such little time. Let us fill it up with serendipity. Let us occupy ourselves with joy.