Yale Daily News

Editor’s Note: The News has chosen to remove students’ last names to protect their identities.

When Sarah was a first year, she enrolled in PSYC 160, “The Human Brain.” All of the quizzes in the class were open book, and she performed well on them. But the final exam –– which was closed note –– “severely overwhelmed” her. She had a panic attack the day before the test, making it impossible for her to focus on studying. The anxiety lasted until she fell asleep that night, prompting her to make cheat sheets on notecards, which she slipped into her pocket the day of the exam.

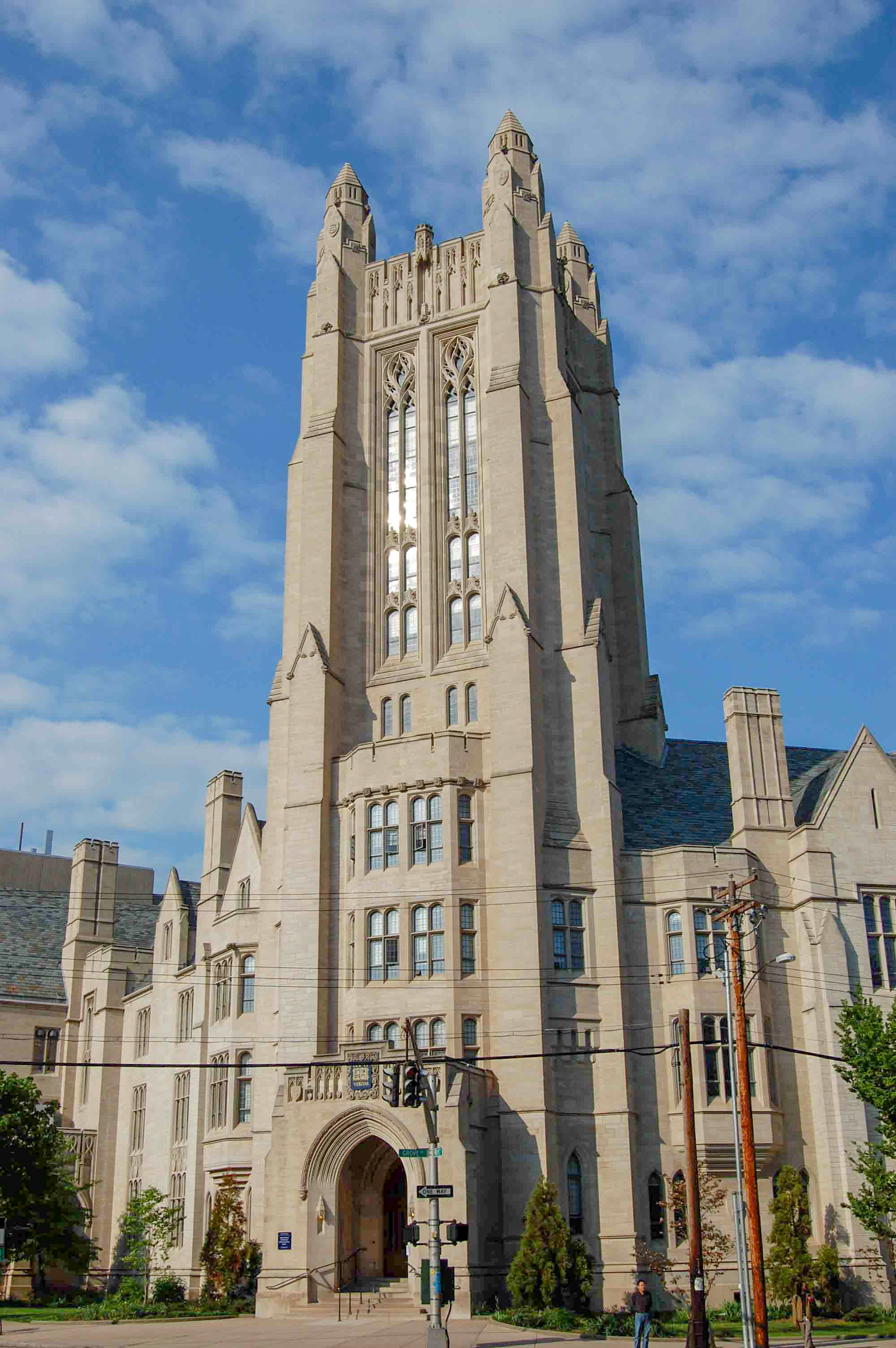

Sarah fared well for the first half of that exam, but fatigue kicked in as she approached its midpoint, and she panicked again. She left the testing area in the Sheffield-Sterling-Strathcona Hall, took a breath and headed to the bathroom where she consulted her notecards before returning to her test.

Sarah was never caught cheating, like many other Yalies.

The News recently conducted a survey on cheating at Yale, and 14 percent of the more than 1,400 undergraduate respondents reported having cheated during their time at the University, while 24 percent reported copying answers from another student’s problem set this past fall. Two percent of respondents did not answer the question.

Twenty-six percent of Yalies reported to have caught someone cheating, and 4 percent did not respond to the question. But of the 191 respondents who said they had cheated at Yale, 8 percent said they had been caught for cheating, 82 percent said they had not been caught and 10 percent did not answer the question. Some of those who were caught had to meet with their professors, their director of undergraduate studies, the dean of their residential college or the Executive Committee before facing the possibility of punishment — such as a zero on the assignment, a citation or being put on academic probation.

Still, only 2 percent of respondents said they had cheated on an exam at Yale, whether they “[looked] stuff up in bathroom on phone,” “opened up [their] book in the middle of a test” or “[looked] at other people’s papers,” according to anonymous responses. But 8 percent of respondents have used a non-prescribed “study drug” — a prescription drug such as Adderall, Ritalin, etc. — to enhance their studying, while 4 percent did not answer the “study drug” question.

“I’m shocked, and I’m very sorry to hear that,” said Dean of Yale College Marvin Chun in response to the survey. “When students cheat, they’re also cheating themselves out of an education. We have many people working on Executive Committee very diligently to ensure academic integrity of all the work that happens at Yale, but it sounds like a lot of cases are going undetected.”

SCIENCES AND MATHEMATICS

Although students reported cheating on subjects in a variety of fields, more respondents said they cheated in science and mathematics classes than in classes related to the social sciences, humanities or engineering.

Mathematics Department Chair Yair Minsky, who says he has not yet dealt with cheating in any of the classes he teaches at Yale, said that while he would not have guessed the numbers, they do not surprise him.

He explained that math can often be an intimidating discipline for many students, especially for non-math majors required to take courses within the department. When talking about problem sets, Minsky said that academic dishonesty is often a “grey area.”

“I think if people are just copying without working, then that’s not good,” Minsky said. “The way we view the whole thing in math with problem sets is that if students don’t do the work for the problem set, they’re just hurting themself because in the exam, they don’t get to do that. They have to do it themselves.”

Stephen Stearns, director of undergraduate studies for Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, said he does not view cheating as a large issue within his department. Still, he said it is not surprising that there could be cheating on problem sets in demanding courses such as Physics 170/171 and Physics 180/181, where an average student spends more than nine hours outside of the classroom solving problem sets per week.

Minsky added that cheating in more quantitative subjects “is a more salient possibility” than cheating in humanities courses that often rely on essays. Less than 1 percent of respondents reported having cheated on an essay or paper this past fall semester.

“I think that it’s an ongoing issue,” Stearns said. “I don’t think it will ever go away because there will always be incentives. The only way to deal with it is to have discussions, make it transparent, have people understand what it means to be academically dishonest and, when people cheat, to punish it. The punishment should fit the crime.”

STUDY DRUGS

Sarah said she has taken Adderall twice to enhance her studying. The first time, she was in her junior year of high school, and she felt pressed to finish a paper on deadline. She took a pill, “and it went great.” So in the fall semester of 2018, under similar high pressure circumstances, she did the same.

“You’re miserable. You’re sad that you can’t sleep,” she said about the effects of the drug. Still, she said that it got the job done.

The News’ survey results, with 8 percent of respondents reporting having used a “study drug,” are in line with those of nationwide studies. A nationwide survey of 10,000 students found that nearly 7 percent of college students had used “study drugs” in order to perform better academically. The same survey found that more than half of students who reported having an Adderall prescription to treat attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, known as ADHD, had received offers from students looking to buy their medications.

Still, psychology professor Jutta Joorman said the News’ survey result “seems a little low,” adding that she felt many students were underreporting study drug usage.

“It is sad that students feel that they have to do this, and I wish they would explore other ways to deal with the stress and pressure,” she said. “It is never a good idea to use prescription drugs for nonmedical purposes, and these drugs do have serious side effects and addiction potential.”

Joorman added that researchers do not yet fully understand the long-term impact of “study drugs” on the brain, which is still developing well into the early twenties. She cited National Institute of Drug Abuse research that shows that college students are particularly less likely to acknowledge the dangerous effects of using ‘study drugs.’

RECRUITED STUDENT ATHLETES

A total of 117 recruited athletes responded to the News’ survey, and out of those respondents, 22 percent reported cheating at some point in their Yale career, while 3 percent did not respond to the question. Eighteen percent of recruited athlete respondents reported using “study drugs,” and 20 percent did not answer — numbers higher than those for all respondents. Thirty-one percent of recruited athletes surveyed responded that they had copied problem set answers during the fall 2018 semester, and 14 percent did not respond to that question.

“It’s disheartening to hear that, but it’s not entirely surprising,” said Juma Sei ’22, a recruited member of the track team.

Sei said that he believes students at Yale often cheat because of the stress, especially when they save problem sets or other assignments for the last minute. Sei added that having to juggle classes, practices, games and homework while also balancing a social life makes being a student athlete “one of the most stressful things you can do” at Yale.

Professors agreed, noting that student athletes’ mandatory time commitments to their sports could be a possible reason for increased cheating rates among them.

Minsky said it may be difficult for students to “optimize everything,” adding that student athletes must invest countless hours in sports, so they might not have as much time for academics as a result. Stearns added that, as a professor, he generally believes that recruited athletes who feel particularly challenged by the competitiveness of Yale might “feel like they have to cheat in order to keep up.”

“The nature of being on a team is more conductive to taking classes together and doing things together, which for some leads to the danger of potentially taking the easy way out in a tough spot,” Jacqueline Hayre-Pérez ’21, a walk-on member of the fencing team, said. But, she noted that she has not seen this happen on her team. Still, while just 26 percent of all survey respondents said that they had caught someone else cheating at Yale, 35 percent of recruited student athletes said they have had this experience, and 20 percent did not respond to the question.

But Hayre-Pérez noted that the higher percentages for recruited athletes might just indicate that they were more honest in their responses.

Director of Athletics Victoria Chun wrote in an email to the News that the Department of Athletics has “absolutely no tolerance for cheating or any other behavior that does not reflect the core values of Yale Athletics and our mission to develop future leaders who can make a meaningful difference in the world.”

Chun added that as a part of the department’s “efforts to provide … students with both the training and the courage to be great leaders,” the Athletic Department is committed to addressing the “underlying pressures and enablers that might cause any student athlete to engage in cheating.”

“The Department of Athletics is fortunate to work closely with the residential college deans, and I plan to look into this survey further with Dean Chun,” Director Chun said. “Since I arrived at Yale, I’ve been extremely impressed at the values and ethics of our student body — and especially of our student athletes — and think it is important we continue to look for ways to develop the leaders Yale is known for.”

CONSEQUENCES

When faculty members believe a student has cheated, they are encouraged to take the case to the Executive Committee, according to the committee’s website. ExComm — comprised of eight Yale College faculty members and 12 undergraduates appointed by Dean Chun — reviews instances “of academic dishonesty on a class assignment or examination,” according to the University website. Faculty members with evidence of cheating can provide the committee with a written statement explaining the infraction. Students aware of cheating are encouraged to report the instance to the course instructor first but can report the instance to a department chair or residential college dean.

The student accused of cheating will then be alerted of the allegations and is allowed to submit a written statement before preparing for a hearing before the Committee. Accused students can call witnesses and answer the panel’s questions at the hearing.

The most recent full academic year for which ExComm data is available is 2016–17. That year, 45 students were charged with academic dishonesty. Of those, no students had their degree withheld, two were suspended, three were put on probation, 21 were reprimanded, eight had charges withdrawn and four were found not guilty. One student was expelled.

When prompted to elaborate on how they reacted when they caught someone cheating, many respondents indicated that they did nothing. The reasons? “Not a snitch.” “I minded my damn business.” “Stayed quiet.” Sarah also said she would never report cheating.

“So the f*** if they’re cheating,” she said. “That’s their business.”

Still, several students interviewed by the News felt otherwise, noting that when students cheat, it lessens the value of their Yale degrees.

Hayre-Pérez said that she believes widespread cheating “degrades … the markers that Yale has set up to measure success,” especially when so many students copy homework assignments.

“I think that’s really a nasty thing because you’re undermining the University’s brand by short-cutting your assignments,” Declan Kunkel ’19 said. “Yes, [a diploma] is a piece of paper, but it’s supposed to be a token of knowledge.”

Dean Chun concurred.

“Students, by cheating at such high rates, they’re devaluing how others will see the value of their education,” Chun said. “We have work to do.”

Still, Sarah said that cheating at Yale is often not students’ preferred option. She said that at high school, she always saw exams as means of cementing knowledge and applying it, and not as the stress-inducing behemoths they can be. She attended a high school with no grades. If she failed a test, she would simply retake it. She said she never had much of a drive to cheat.

But Yale has been different. While Sarah still tries to focus on learning, the pressures she faces on a daily basis often push her to extremes.

“Here, the stakes are so much higher. I’ve recently found myself in a very complicated, stressful situation with Yale … . If you trip, you will not have the chance to stand back up … . You don’t have the time. You don’t have the time to have moments of weakness,” Sarah said. “I guess cheating comes in when you feel you don’t have a choice.”

Asha Prihar | asha.prihar@yale.edu

Carly Wanna | carly.wanna@yale.edu

Correction, Feb. 7 : An earlier version of this article reported Stephen Stearns as the director of undergraduate studies for Geology and Geophysics. In fact, he is the director of undergraduate studies for Ecology and Evolutionary Biology.

Clarification, Feb. 7: This story has been updated to more accurately reflect Stephen Stearns’ sentiments on Physics 180/181 and 170/171.