Sophie Henry

When I first moved to Ashbourne, New York, I wasn’t alarmed to find parents raising their young in tanks. Parents have always been raising their young strategically. Having lived on several different continents as a child, I’ve witnessed various methods of child-rearing — cages, pens, fences, terrariums. Different structures to account for different fears; tactics bent on absorbing the climate. Maybe the neighborhood fears another Genesis flood, I conjectured, and I pictured it: windows collapsing with the crescendo of moving water. No. The water would seep up from beneath the carpet — starting in squelches between toes, then gradually rising to tickle slumbering ears. New York, a submarine empire suspended in time, its demographics diversified to include nekton and zooplankton.

I first observed the tanks through the open blinds of a neighbor’s window. Night had shrouded the streets to the extent that it was difficult to use my bedroom window as anything more than a mirror. Piercing through the black, a neon green rectangle flickered, replacing my face and encapsulating what seemed to be the silhouette of a child’s legs. As I peered closer, I noticed that the rectangle was actually a tank in the window across the street. The silhouette sunk lower in the tank, fruitlessly lurching against a pair of hands pressing him down. I forgot to breathe as I watched the child’s delicate skin ripple and break from the impact of kicking against a lid clamping him down and closing him off from the world. His chest heaved in an attempt to fill his lungs with anything — even water — and I fought the urge to dash across the street.

This is completely normal, I assured myself. This town is just like any other.

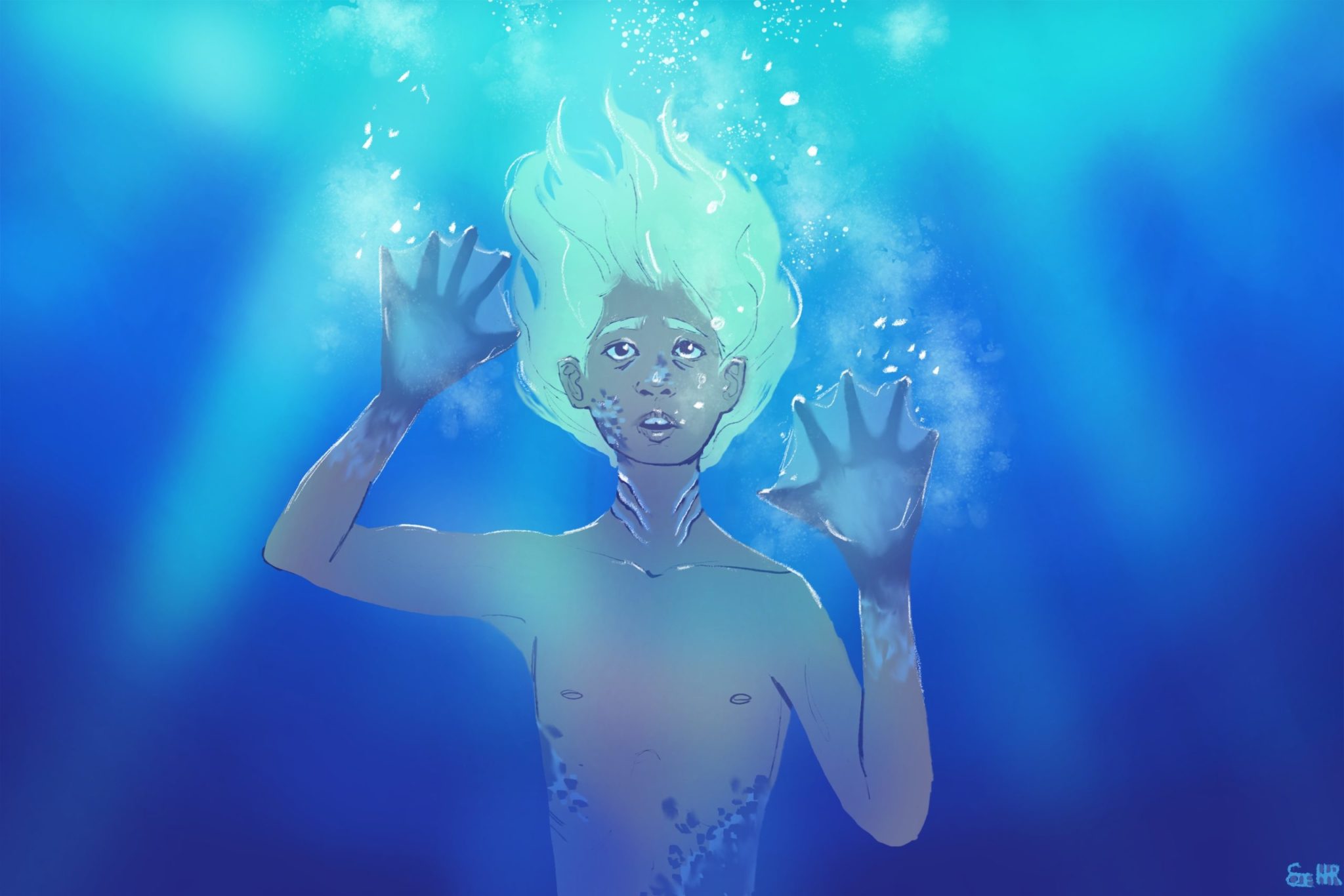

Just then, as the boy mustered one last kick, the green liquid peeled back his flesh, unveiling grey shark-skin beneath. Like mouths, gills resembling tally marks opened between his face and ears; his pale hair drifted to the floor of the tank. When his hands reopened, thin, ghostlike webbing bloomed in the space between his fingers. His new strokes were lithe and froglike.

I shuddered a sigh of relief. Ignoring the raw, red crescents dotted across my palms, I resumed my studying.

Every afternoon since then, I have returned to my windowsill to watch the shark-boy grow. A recent development: two adults — I assume, his parents — took a more active role in his physical development. I could read the father’s lips: Bite, bite, he would taunt, brandishing a steak dripping ruby above his head. He tossed it up with the piercing accuracy of an insult, and the boy sprung up, drenching his parents’ clothes while snapping a juicy piece between rows of piercing teeth. The parents stepped back, proudly admiring their work.

One day, the mother’s eyes met mine. She shut the blinds and that’s how they remained.

At school, I noticed these similar, sharklike features on my peers. In the halls, some students flaunted their agility by pumping their gills open and closed. The insides resembled the undersides of chanterelle mushrooms, the kind I would often uproot. Conversely, many peers were secretive, shrouding their gills with strands of deliberately placed hair.

School was a cold dive into a den of sharks: when raising my hand to answer a question, the wide, glinting eyes of my classmates raised goosebumps on every inch of my arm. As I strode down the hallway, tension curled its heavy fingers around my throat; my peers breathed like wire traps, keen to masticate the leathery carcasses of their peers in the snap of a moment.

Sharks lurking in the lull of the ocean deep.

“Opioids activate receptors on nerve cells and release your …” the biology teacher, Ms. Brown, droned on in the background. Students’ faces were dyed technicolor in the glare of their phone screens, their webbed hands scrolling surreptitiously. I glanced down at my web-less hands, feeling naked. My eyes landed on the desk beside me, where a girl doodled on the margins of her notes, balloons of color blooming from her highlighters. Jellyfish, I mused. Then, I realized with a gasp: her fingers weren’t webbed. My gaze immediately jumped to her neck and found the signature, shark-like gills lining her neck: only they were dormant, like pencilled tally marks and nothing more.

In a burst of impulse, I took out a sticky note.

Hey, my name is Aria. I like your jellyfish, I wrote, gingerly placing the note on her desk.

She flicked her eyes to the note and flashed me a grin. I’m Ashley. Let’s talk later, she mouthed.

“This is — BY FAR — my favorite part of the school.” Ashley swung open a small mahogany door, and sunlight spilled through the opening. Inside, the late sun cradled statues, art stands, and canvas in a golden halo. A freshly-painted mural spread across the cerulean wall: eyes and eyes and eyes, blending together and tearing apart.

I paced around the room, hovering my hand over the paintings and the statues. “I guess Ashbourne’s art department isn’t as bad as they say it is.”

“Oh but it is,” Ashley interjected. “That … and that … and that.” She pointed. “All my work.”

“Oh but you’re fucking brilliant,” I said, face frozen in awe.

Ashley blushed a deep red and mumbled thanks.

I took her hands in mine, and stared into her eyes. “We need to paint together sometime.”

“How about … right now?” She slid open the cabinet in the wall behind her, displaying an array of paints. We shared a mischievous grin before running to grab brushes on the counter to begin our work.

During the next few months of school, Ashley and I became inseparable. After bio, she would show me a new part of the school, and then we’d retreat into the art room until the latest bus left the school. One day, I missed my stop and she offered to bring me to her home.

As we descended the school bus to the path leading up to her house, Ashley’s steps faltered. The spasmodic staccato of her gait indicated a desire to retreat, but she continued dragging her feet forward. Gingerly, Ashley slipped her key into the front door and twisted, her movements growing more frantic as the key didn’t budge. As our eyes slid up the length of the door, we found a pair of wide eyeballs staring back: jiggling in their sockets like boiled eggs. The door crashed open, revealing a hulking man.

“You’re late,” he spat. “Who’s this?” he demanded. “Do you want her to see your tank, too?”

Ashley’s eyes darted back at me. “N-no,” she stuttered. “But —”

Feeling the sudden pressure in my bladder, I blurted if I could use the restroom. The man took a reluctant step back, pointing directions to the nearest restroom.

While washing my hands, I jolted from a loud crash. Glancing out from the narrow door slit, I gazed in awe at her tank — it dominated her room, spanning its length and rising halfway up the dimly-lit wall. Mr. Gong loomed like an apparition, his hands spread out over the lid while a woman — I assumed Mrs. Gong— lurked from afar. Beneath it, fluorescent lights cast a gradient of translucent shadows across the carpeted floor.

“Open your gills,” he demanded. The solution within shook from the impact of his baritone. That’s when I noticed Ashley clinging beneath the lid, still as a stone. Her hair drifted from the clips in her hair, unveiling five long knife wounds. They weren’t gills, really. They were dormant, premature, sleeping.

Ashley’s huge, saucer-like eyes blinked frantically in the tank, growing scarlet from the solution. She cupped her hands around her neck in a strained attempt to breathe. Her skin was wrinkled and pale, and I knew she hadn’t evolved, not like the boy I’d seen grow in the tank. Her very anatomy protested against the unrealistic expectations weighing down on her.

I felt my legs wind like springs, ready to pounce, when I found Ashley …morphing. A film glazed over her eyes, and a sense of calm pulled over her face like a new skin, her breath sputtering from the gills on the sides of her head. I could see her new self bursting to the surface.

My gaze flicked to her mother. Her eyes glinted, nails digging into her palms. Her jaw shifted as her teeth ground beneath her skin. But she didn’t move.

Sitting cross-legged with my back absorbing the cool of the tank, I waited for my friend as her parents left. “That’s such a weird decoration for a shark,” I mumbled, surveying a likely self-painted Eiffel Tower mural with plastic jewels plastered in glitter-glue.

I wiped the thought away as clumps of water tumbled and plopped to the floor from Ashley’s hair, which was tousled like kelp. I glanced at Ashley, half expecting an empty shell where a girl used to be. She asked: “Did you finish the bio lab?”

I shook my head.

After the accidental encounter, I sat sheepishly with the Gong family and pretended Ashley hadn’t been struggling in frigid waters for the past hour. Her mother conjured an entire instant Italian feast, complete with a baked Costco pizza sprinkled with pre-marinated tomatoes and anchovies. Making conversation, Mrs. Gong asked which APs I was taking, what I scored on the SATs, and what tank model I kept at home. While I obediently listed off my APs, I caught Mrs. Gong side-eyeing her daughter.

“Ashley should’ve taken more AP classes,” she murmured.

After that day, I felt a different energy emanating from Ashley. In contrast to her calm, deadly presence underwater, above land, she became anxiety incarnate. In class, her knee sporadically bounced beneath her desk, and her expressions became tight and twitchy. Her usually clean-brushed hair and mascara-swept lashes were replaced with tousled hair and dry, red eyes.

During the AP Biology test the next week, I discovered the root of the problem.

Silence amplified the pulsing of asynchronized clocks: analog clocks, digital clocks. The clicking of pens and the bobbing of knees.

In my peripheral vision, Ashley hurriedly surveyed the classroom and shakily copied down the answers from a hidden slip of paper, almost dropping her pen before stopping it in its path with a loud smash.

She hyperventilated as if she didn’t know the next time she would come up for air. A student complained of the noise as Ashley began to cry.

By wearing a skin she didn’t fit into, Ashley was beginning to slip. And she wasn’t the only one.

Students at school gasped for air without being underwater. If they weren’t focusing, pure oxygen sputtered through their collapsed gills, and their eyes swam like whirlpools from suffocation. Their legs wobbled like vestigial structures. Each night, they typed away at their computers as if working were the only thing keeping them afloat — keeping them from drowning. After all, they’re sharks, I thought.

During lunch, I mustered the courage to warn Ashley.

“Hey, Ashley, I’m worried for you,” I breathed. “Cheating isn’t fair to anyone else, or yourself, either.”

“Mind your own business,” snapped Ashley. Everyone else at the table went silent, and I sunk into my chair as if tethered to an anchor.

I should’ve noticed already: the power dynamic between friends, the utilitarian approach to weighing and manipulating relationships. Here, friends were like means to an end: the Future Connection, the Homework Helper, the Popularity Booster. In the way some students stole college portfolios, essays, personas — and yet no one was speaking out. In this symbiotic web of manipulated relationships, I had committed a blunder and tumbled through the cracks.

Success is king here, I thought, and everything else follows.

“Let’s calm down,” chirped Aria with her perfectly symmetrical, plastic smile. It was the same one others wore when anticipating the results of a contest or test. Wishing for your undoing. After all, success is relative to the failure of others.

From then on, I built a mental cocoon distancing myself from my peers. It was a simple feat — even the texture of their skin pricked like tiny teeth called placoid scales. As if I had the electroreceptor organs of a shark, I easily maneuvered the subtle shifts in the atmosphere through the pores of my skin. I found that the longer I stayed, however, the more I fell prey to the siren song of a completely self-centered world devoid of ethics. If dishonesty pays, I thought, then what’s stopping me from doing the same?

When I returned home that day, my parents were waiting for me with a tank of their own.

“Of course, there’s no pressure to use it,” Dad insisted. “It’s completely up to— ”

“But we highly recommend it,” Mom interrupted. She paused. “No pressure, of course.”

I took note of the strong recommendation and bit back my disgust. Acid reflux lurched against the roof of my mouth. Living in a tank isn’t living, I thought unconvincingly. Was I really giving in? No — you’ll forget to breathe. You’ll lose yourself, the way Ashley did. And that boy. And countless others.

Back at school, the speakers crackled while requesting a moment of silence. Amanda Green, they said, cause of death — to be determined. Discovered with pills scattered around her body.

Everyone knows why she passed, I realized in the way their beady eyes remained dry, without a hint of moisture. Jordan scrolled through Instagram while the homeroom teacher, Mrs. Lyon squeezed her palms together in prayer. I closed my eyes and tried fruitlessly to conjure the girl I had never heard of until her death. I wondered if she was the type to hide gills behind strands of hair or flash them like medallions of war. I wondered which tank model she used.

I imagined Amanda Green, sprawled on the carpeted floor, pills tumbling into the crevices in her throat. I saw her gasping for air, clutching her collarbone as her gills heaved into overdrive. Her ghostly hands caressed my skin as phantom pains, and she seeped like stinging seawater into the cuts in my skin.

I gasped. How was I to survive in this ecosystem that cast aside those who couldn’t adapt?

My knees buckled as my fear grew into a desperate cry for survival. Like a taut violin string ready to snap, my body was on the brink of bursting open.

In my room, I took a step back, watching the tank with tired, weary eyes. Surprisingly, I didn’t recall the memories of Ashley and the boy, nearly drowning in their respective green tanks. Instead, I pictured:

Mom, massaging lotion into her palms, cracked dry like asphalt after a long day at the nursery.

Dad, blue light sinking into the furrows of his forehead as he typed in the kitchen with the lights off to allow my sister and me a good night’s sleep.

Mom and Dad, sacrificing everything for my success. My eyes swam.

The realization crashed into me like a tidal wave: I would become a shark for them. But did they truly comprehend the sort of monster their daughter would become?

I collapsed back onto my mattress, eyes glued to the tank. They lingered there until the lights faded.

Today, I woke to the groan of a tank filling with water. The cadencial drip drip of water leaking from the faucet resembled an elegy. I rested my fingertips on the edge of the tank and peered down at my distorted reflection. With an eerie sense of calm, I stripped off my clothes and slid beneath the water. I surrendered to the cool liquid and let it consume me. Now, at the base of the tank, I watch my reflection in a trance. The gentle ripple of the surface refracts light to form patterns across my skin, intertwining like bodies rhythmically collapsing into each other. The ambient noise of the outside world ceases to be comprehensible; waves of sound thumping against a barricade of glass.

I have gills, I think. My smile: perfectly symmetrical, all lips. My eyes: bloodshot and glazed over. I chuckle, and air bubbles scramble to the surface. Was I expecting to see something new hatch from the skin I’ve concocted for myself?

The reflective sides of the glass mirror each other and multiply my image to infinitudes. It looks like a time vortex or a pathway to another dimension. My future has never felt so infinite, so tangible as it does encased in a tank conceived of glass. The water doesn’t unlatch my skin or reveal anything new; instead, it cradles my every curve and corner in a fluid embrace.

Always swimming, swimming from my own blood.

I don’t want to stop.

In my town, children click their mechanical pencils, scroll through Instagram, stare at their reflections on dark tank surfaces. Here, children forget to breathe, forgo sleep, grow skin like sandpaper.

And like many places, our town trades our present for the future.

Doesn’t yours?